363:, to Archilochus, but reneged on the agreement, and the poet retaliated with such eloquent abuse that Lycambes, Neobule and one or both of his other daughters committed suicide. The story later became a popular theme for Alexandrian versifiers, who played upon its poignancy at the expense of Archilochus. Some modern scholars believe that Lycambes and his daughters were not actually the poet's contemporaries but fictional characters in a traditional entertainment. According to another view, Lycambes as an oath-breaker had marked himself out as a menace to society and the poet's invective was not just personal revenge but a social obligation consistent with the practice of 'iambos'.

185:

696:, but Archilochus uses it here to communicate the need for emotional moderation. His use of the meter isn't intentionally ironic, however, since he didn't share the tidy functionalism of later theorists, for whom different meters and verse-forms were endowed with distinctive characters suited to different tasks – his use of meter is "neutral in respect of ethos". The following verse is indicative too of the fragmentary nature of Archilochus's extant work: lines 2 and 3 are probably corrupted and modern scholars have tried to emend them in various ways, though the general meaning is clear.

40:

254:

1929:

347:

757:

217:. There is nothing in those two fragments to suggest that Archilochus is speaking in those roles (we rely entirely on Aristotle for the context) and possibly many of his other verses involved role-playing too. It has even been suggested by one modern scholar that imaginary characters and situations might have been a feature of the poetic tradition within which Archilochus composed, known by the ancients as

387:. A Naxian warrior named Calondas won notoriety as the man that killed him. The Naxian's fate interested later authors such as Plutarch and Dio Chrysostom, since it had been a fair fight yet he was punished for it by the gods: He had gone to the temple of Apollo at Delphi to consult the oracle and was rebuked with the memorable words: "You killed the servant of the Muses; depart from the temple."

456:"For of the two poets who for all time deserve to be compared with no other, namely Homer and Archilochus, Homer praised nearly everything ... But Archilochus went to the opposite extreme, to censure; seeing, I suppose, that men are in greater need of this, and first of all he censures himself ...", thus winning for himself "... the highest commendation from heaven." –

493:"... not all his iambic and trochaic poetry was invective. In his elegiacs we find neat epigrams, consolatory poems and a detailed prediction of battle; his trochaics include a cry for help in war, an address to his troubled soul and lines on the ideal commander; in his iambics we find an enchanting description of a girl and Charon the carpenter's rejection of tyranny."

851:"Tellis appears to be in his late teens, Cleoboea as still a girl and she has on her knees a chest of the sort that they are accustomed to make for Demeter. With regard to Tellis I heard only that he was the grandfather of Archilochus and they say that Cleoboea was the first to introduce the rites of Demeter to Thasos from Paros." – Pausanias 10.28.3

334:'s boat with the priestess of Demeter. The poet's father, Telesicles, also distinguished himself in the history of Thasos, as the founder of a Parian colony there. The names 'Tellis' and 'Telesicles' can have religious connotations and some modern scholars infer that the poet was born into a priestly family devoted to Demeter. Inscriptions in the

890:

pre-eminent among holy islands, but

Archilochus spewed forth frightful reproach and a hateful report against our family. We swear by the gods and spirits that we did not set eyes on Archilochus either in the streets or in Hera's great precinct. If we had been lustful and wicked, he would have not wanted to beget legitimate children from us." –

503:) – elegy aimed at some degree of decorum, since it employed the stately hexameter of epic, whereas the term 'iambus', as used by Alexandrian scholars, denoted any informal kind of verse meant to entertain (it may have included the iambic meter but was not confined to it). Hence the accusation that he was "too iambic" (see

593:, yet he was also censured by them as the archetypal poet of blame – his invectives were even said to have driven his former fiancée and her father to suicide. He presented himself as a man of few illusions either in war or in love, such as in the following elegy, where discretion is seen to be the better part of valour:

484:"We find in him the greatest force of expression, sententious statements that are not only vigorous but also terse and vibrant, and a great abundance of vitality and energy, to the extent that in the view of some his inferiority to anyone results from a defect of subject matter rather than poetic genius."

382:

His combative spirit also expressed itself in warfare. He joined the Parian colony on Thasos and battled the indigenous

Thracians, expressing himself in his poems as a cynical, hard-bitten soldier fighting for a country he doesn't love ("Thasos, thrice miserable city") on behalf of a people he scorns

204:

A considerable amount of information about the life of

Archilochus has come down to the modern age via his surviving work, the testimony of other authors, and inscriptions on monuments, yet it all needs to be viewed with caution – the biographical tradition is generally unreliable and the fragmentary

889:

include the following by a certain

Dioscorides, in which the victims are imagined to speak from the grave: "We here, the daughters of Lycambes who gained a hateful reputation, swear by the reverence in which this tomb of the dead is held that we did not shame our virginity or our parents or Paros,

475:

of Homer. Homer did not create the epic hexameter, however, and there is evidence that other meters also predate his work. Thus, though ancient scholars credited

Archilochus with the invention of elegy and iambic poetry, he probably built on a "flourishing tradition of popular song" that pre-dated

241:

from the sanctuary include quoted verses and historical records. In one, we are told that his father

Telesicles once sent Archilochus to fetch a cow from the fields, but that the boy chanced to meet a group of women who soon vanished with the animal and left him a lyre in its place – they were the

224:

The two poems quoted by

Aristotle help to date the poet's life (assuming of course that Charon and the unnamed father are speaking about events that Archilochus had experienced himself). Gyges reigned 687–652 BC and the date of the eclipse must have been either 6 April 648 BC or 27 June

209:, that Archilochus sometimes role-played. The philosopher quoted two fragments as examples of an author speaking in somebody else's voice: in one, an unnamed father commenting on a recent eclipse of the sun and, in the other, a carpenter named Charon, expressing his indifference to the wealth of

488:

Most ancient commentators focused on his lampoons and on the virulence of his invective, yet the extant verses (most of which come from

Egyptian papyri) indicate a very wide range of poetic interests. Alexandrian scholars collected the works of the other two major iambographers, Semonides and

370:

imply that the poet had a controversial role in the introduction of the cult of

Dionysus to Paros. It records that his songs were condemned by the Parians as "too iambic" (the issue may have concerned phallic worship) but they were the ones who ended up being punished by the gods for impiety,

430:

This couplet testifies to a social revolution: Homer's poetry was a powerful influence on later poets and yet in Homer's day it had been unthinkable for a poet to be a warrior. Archilochus deliberately broke the traditional mould even while adapting himself to it. "Perhaps there is a special

342:

There is no evidence to back isolated reports that his mother was a slave, named Enipo, that he left Paros to escape poverty, or that he became a mercenary soldier – the slave background is probably inferred from a misreading of his verses; archaeology indicates that life on Paros, which he

489:

Hipponax, in just two books each, which were cited by number, whereas

Archilochus was edited and cited not by book number but rather by poetic terms such as 'elegy', 'trimeters', 'tetrameters' and 'epodes'. Moreover, even those terms fail to indicate his versatility:

439:) and for "the unseemly and lewd utterances directed towards women", whereby he made "a spectacle of himself" He was considered "... a noble poet in other respects if one were to take away his foul mouth and slanderous speech and wash them away like a stain" (

912:"I have no liking for a general who is tall, walks with a swaggering gait, takes pride in his curls, and is partly shaven. Let mine be one who is short, has a bent look about the shins, stands firmly on his feet, and is full of courage." – Fragment 114

431:

relevance to his times in the particular gestures he elects to make: The abandonment of grandly heroic attitudes in favour of a new unsentimental honesty, an iconoclastic and flippant tone of voice coupled with deep awareness of traditional truths."

229:

of a cenotaph, dated around the end of the seventh century and dedicated to a friend named in several fragments: Glaucus, son of Leptines. The chronology for Archilochus is complex but modern scholars generally settle for c. 680 – c. 640 BC.

343:

associated with "figs and seafaring", was quite prosperous; and though he frequently refers to the rough life of a soldier, warfare was a function of the aristocracy in the archaic period and there is no indication that he fought for pay.

451:

banished the works of Archilochus from their state for the sake of their children "... lest it harm their morals more than it benefited their talents." Yet some ancient scholars interpreted his motives more sympathetically:

350:"Look Glaucus! Already waves are disturbing the deep sea and a cloud stands straight round about the heights of Gyrae, a sign of storm; from the unexpected comes fear." The trochaic verse was quoted by the Homeric scholar

780:. About half of these fragments are too short or too damaged to discern any context or intention (some of them consisting of single words). One of the longest fragments (fragment 13) has ten nearly complete lines.

434:

Ancient authors and scholars often reacted to his poetry and to the biographical tradition angrily, condemning "fault-finding Archilochus" for "fattening himself on harsh words of hatred" (see Pindar's comment

200:, late 5th century BC. Archilochus was involved in the Parian colonization of Thasos about two centuries before the coin was minted. His poetry includes vivid accounts of life as a warrior, seafarer and lover.

515:

or pipe, whereas the performance of iambus varied, from recitation or chant in iambic trimeter and trochaic tetrameter, to singing of epodes accompanied by some musical instrument (which one isn't known).

371:

possibly with impotence. The oracle of Apollo then instructed them to atone for their error and rid themselves of their suffering by honouring the poet, which led to the shrine being dedicated to him. His

225:

660 BC (another date, 14 March 711 BC, is generally considered too early). These dates are consistent with other evidence of the poet's chronology and reported history, such as the discovery at

358:

The life of Archilochus was marked by conflicts. The ancient tradition identified a Parian, Lycambes, and his daughters as the main target of his anger. The father is said to have betrothed his daughter,

237:) was established on his home island Paros sometime in the third century BC, where his admirers offered him sacrifices, as well as to gods such as Apollo, Dionysus, and the Muses. Inscriptions found on

205:

nature of the poems does not really support inferences about his personal history. The vivid language and intimate details of the poems often look autobiographical yet it is known, on the authority of

807:, Volume LXIX (Graeco-Roman Memoirs 89, 2007). A discovery of a fragment of writing by Archilochus contained a citation of a proverb that was important to the proper interpretation of a letter in the

39:

1723:

Archiloque, Fragments, texte établi par François Lasserre, traduit et commenté par André Bonnard, Collection des Universités de France, publié sous le patronage de l'Association Guillaume Budé

176:. He is celebrated for his versatile and innovative use of poetic meters, and is the earliest known Greek author to compose almost entirely on the theme of his own emotions and experiences.

760:

A small papyrus scrap first published in 1908 which is derived from the same ancient manuscript of Archilochus that yielded the most recent discovery (P.Oxy. VI 854, 2nd century CE).

585:

Although his work now only survives in fragments, Archilochus was revered by the ancient Greeks as one of their most brilliant authors, able to be mentioned in the same breath as

555:). He did in fact compose some lyrics but only the smallest fragments of these survive today. However, they include one of the most famous of all lyric utterances, a hymn to

246:. Not all the inscriptions are as fanciful as that. Some are records by a local historian of the time, set out in chronological order according to custom, under the names of

476:

Homer. His innovations however seem to have turned a popular tradition into an important literary medium. His merits as a poet were neatly summarized by the rhetorician

383:

yet he values his closest comrades and their stalwart, unglamorous commander. Later he returned to Paros and joined the fight against the neighbouring island of

772:(tom. II, 1882) There are about three hundred known fragments of Archilochus' poetry, besides some forty paraphrases or indirect quotations, collected in the

1416:

306:. According to tradition, Archilochus was born to a notable family on Paros. His grandfather (or great-grandfather), Tellis, helped establish the cult of

660:

Like other archaic Greek poets, Archilochus relied heavily on Homer's example for his choice of language, particularly when using the same meter,

1977:

2033:

640:

Archilochus was much imitated even up to Roman times and three other distinguished poets later claimed to have thrown away their shields –

233:

Whether or not their lives had been virtuous, authors of genius were revered by their fellow Greeks. Thus a sanctuary to Archilochus (the

1942:

242:

Muses and they had thus earmarked him as their protégé. According to the same inscription, the omen was later confirmed by the oracle at

1952:

668:), but even in other meters the debt is apparent – in the verse below, for example, his address to his embattled soul or spirit,

1972:

1947:

1911:

1868:

1836:

1815:

1608:

1299:

981:

1957:

2018:

1887:

1524:

1214:

860:

The name 'Enipo' has connotations of abuse (enipai), which is curiously apt for the mother of a famous iambographer.

258:

507:) referred not to his choice of meter but his subject matter and tone (for an example of his iambic verse see

1962:

2003:

257:

Ionic capital from the grave of Archilochus, with inscription "Here lies Archilochus, son of Telesicles",

2008:

2028:

351:

508:

2023:

1998:

1993:

184:

1897:

323:

1748:

682:

with the final syllable omitted), a form later favoured by Athenian dramatists because of its

2013:

1933:

1204:

551:– his range exceeded their narrow criteria for lyric ('lyric' meant verse accompanied by the

314:

near the end of the eighth century BC, a mission that was famously depicted in a painting at

273:

1928:

8:

812:

808:

641:

819:, with the same proverb: "The bitch by her acting too hastily brought forth the blind."

1783:

1460:

951:

800:

661:

331:

302:

20:

1907:

1883:

1864:

1832:

1811:

1766:

Moran, William L. (1978). "An Assyriological gloss on the new Archilochus fragment".

1604:

1520:

1295:

1210:

977:

955:

497:

One convenient way to classify the poems is to divide them between elegy and iambus (

281:

1943:

Introduction to Archilochos and translation of A's longest fragment by Guy Davenport

1850:

1775:

943:

548:

444:

297:

264:

Snippets of biographical information are provided by ancient authors as diverse as

165:

112:

1967:

777:

1901:

1858:

1826:

1805:

877:, or a mythological allusion to the rocks on which the Lesser Ajax met his death.

969:

839:

816:

520:

457:

384:

293:

218:

210:

169:

148:

1968:

Zweisprachige Textauswahl zu den griechischen Lyrikern mit zusätzlichen Hilfen

1061:

Van Sickle (October–November 1975), "Archilochus: A New Fragment of an Epode"

947:

354:, who said that Archilochus used the image to describe war with the Thracians.

1987:

765:

560:

1854:

1846:

931:

835:

687:

544:

1517:

Archilochus, Alcman, Sappho: Three Lyric Poets of the Seventh Century B.C.

692:

686:

character, expressing aggression and emotional intensity. The comic poet

519:

The Alexandrian scholars included Archilochus in their canonical list of

469:

628:

But at least I got myself safely out. Why should I care for that shield?

1937:

1804:

Brown, Christopher (1997). "Archilochus". In Gerber, Douglas E. (ed.).

788:

675:

477:

319:

1787:

524:

472:

372:

253:

238:

206:

1963:

Archilochus Bilingual Anthology (in Greek and English, side by side)

741:

But delight in things that are delightful and, in hard times, grieve

1882:. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

1779:

1542:

1393:

792:

735:

Now from this side and now that, enduring all such strife up close,

679:

645:

556:

536:

532:

528:

418:

346:

339:

285:

1377:

1375:

974:

Travelling Heroes: Greeks and their myths in the epic age of Homer

1738:, ed. Karen Weisman (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2010) 13-45.

1677:

1045:

1043:

1041:

995:

993:

784:

360:

307:

269:

247:

756:

1497:

1372:

1304:

743:

Not too much – appreciate the rhythm that controls men's lives.

733:

Bear up, hold out, meet front-on the many foes that rush on you

649:

590:

448:

315:

311:

277:

265:

243:

226:

189:

1659:

1657:

1601:

Sappho's Lyre: Archaic lyric and women poets of ancient Greece

1038:

990:

1683:

886:

874:

796:

709:

690:

employed it for the arrival on stage of an enraged chorus in

674:, has Homeric echoes. The meter below is trochaic tetrameter

669:

665:

586:

564:

540:

512:

498:

405:

376:

327:

289:

214:

197:

193:

173:

152:

74:

1709:

Archilochus fr. 128, quoted by Stobaeus (3.20.28), cited by

1294:

Encyclopedia of ancient Greece By Nigel Guy Wilson Page 353

115:

1654:

1413:

552:

440:

338:

identify Archilochus as a key figure in the Parian cult of

136:

130:

1278:

1276:

1274:

1272:

739:

Nor, defeated, throw yourself lamenting in a heap at home,

569:, in which the first word imitates the sound of the lyre.

1016:

1014:

1012:

1010:

1008:

834:

While these have been the generally accepted dates since

124:

44:

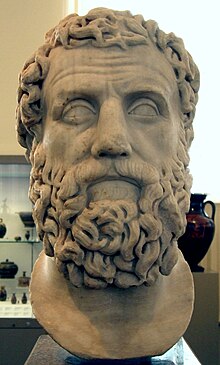

Bust of a bearded man, possibly Archilochus. Roman copy (

731:

My Soul, my Soul, all disturbed by sorrows inconsolable,

1642:

1419:(vol. I, p. 376 Adler) = Aelian fr. 80 Hercher, trans.

1269:

1173:

783:

Thirty previously unknown lines by Archilochus, in the

737:

Never wavering; and should you win, don't openly exult,

1137:

1100:

1005:

903:"The of all the Greeks have come together in Thasos".

776:

edition (1958, revised 1968) by François Lasserre and

764:

Fragments of Archilochus' poetry were first edited by

631:

Let it go. Some other time I'll find another no worse.

1088:

547:, but he was not included in the Alexandrian list of

139:

133:

121:

1185:

543:. Modern critics often characterize him simply as a

127:

1978:

Archilochos of Paros and Archilochos' Beloved Paros

1617:

1530:

1257:

1245:

625:

Unwillingly near a bush, for it was perfectly good,

118:

48:

2nd century BC) of Greek original (4th century BC).

1853:(1985). "Elegy and Iambus". In Easterling, P. E.;

1365:Denis Page, 'Archilochus and the Oral Tradition',

1233:

1149:

1026:

531:, yet ancient commentators also numbered him with

468:The earliest meter in extant Greek poetry was the

607:αὐτὸν δ' ἔκ μ' ἐσάωσα· τί μοι μέλει ἀσπὶς ἐκείνη;

1985:

1845:

1603:. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

1586:

1548:

1503:

1381:

1310:

1049:

999:

1464:1985. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 137/

723:μὴ λίην· γίνωσκε δ᾽ οἷος ῥυσμὸς ἀνθρώπους ἔχει.

715:στέρνον, ἐν δοκοῖσιν ἐχθρῶν πλησίον κατασταθείς

1973:SORGLL: Archilochos 67; read by Stephen Daitz

838:(1941), some scholars disagree; for instance,

713:ἄνα δέ, δυσμενέων δ᾽ ἀλέξευ προσβαλὼν ἐναντίον

1860:The Cambridge History of Classical Literature

601:Ἀσπίδι μὲν Σαΐων τις ἀγάλλεται, ἥν παρὰ θάμνῳ

423:and skilled in the lovely gift of the Muses.

250:. Unfortunately, these are very fragmentary.

16:Ancient Greek lyric poet (c. 680 – c. 645 BC)

787:meter, describing events leading up to the

721:ἀλλὰ χαρτοῖσίν τε χαῖρε καὶ κακοῖσιν ἀσχάλα

407:Εἰμὶ δ' ἐγὼ θεράπων μὲν Ἐνυαλίοιο ἄνακτος,

38:

751:

1824:

1663:

1648:

1598:

1564:, Nigel Wilson (ed.), Routledge, page 76

1282:

1179:

1020:

755:

719:μηδὲ νικηθεὶς ἐν οἴκωι καταπεσὼν ὀδύρεο.

717:ἀσφαλέως· καὶ μήτε νικῶν ἀμφαδὴν ἀγάλλεο

622:) now delights in the shield I discarded

345:

252:

183:

1560:Sophie Mills (2006), 'Archilochus', in

976:. London, UK: Allen Lane. p. 388.

711:θυμέ, θύμ᾽ ἀμηχάνοισι κήδεσιν κυκώμενε,

703:

701:

399:

397:

390:

1986:

1877:

1768:Harvard Studies in Classical Philology

1710:

1636:

1536:

1491:

1446:

1433:

1432:Valerius Maximus, 6.3, ext. 1, trans.

1420:

1401:

1353:

1340:

1323:

1227:

1191:

1167:

1131:

1118:

1082:

930:

559:with which victors were hailed at the

2034:Epigrammatists of the Greek Anthology

1980:: documentaries by Yannis Tritsibidas

1803:

1765:

1734:Gregory Nagy, "Ancient Greek Elegy",

1623:

1263:

1251:

1143:

1106:

1032:

409:καὶ Μουσέων ἐρατὸν δῶρον ἐπιστάμενος.

300:and several anonymous authors in the

1896:

1807:A Companion to the Greek Lyric Poets

1239:

1206:A Companion to the Greek Lyric Poets

1155:

1094:

842:(2008) dates him c. 740–680 BC.

595:

436:

1461:The Art and Culture of Early Greece

968:

934:(1941). "The date of Archilochus".

604:ἔντος ἀμώμητον κάλλιπον οὐκ ἐθέλων·

322:. The painting, later described by

19:For the genus of hummingbirds, see

13:

610:Ἐρρέτω· ἐξαῦτις κτήσομαι οὐ κακίω.

14:

2045:

1921:

1903:Studies in Greek Elegy and Iambus

1725:(Paris, 1958; 2nd ed. rev., 1968)

811:language from the emperor of the

799:, have been identified among the

577:αὐτός τε καὶ Ἰόλαος, αἰχμητὰ δύο.

1927:

1736:The Oxford Handbook of the Elegy

1519:University of California Press.

1445:Dio Chrysostom 33.11–12, trans.

539:as the possible inventor of the

511:). Elegy was accompanied by the

111:

1797:

1759:

1741:

1728:

1716:

1703:

1690:

1669:

1629:

1592:

1567:

1562:Encyclopaedia of Ancient Greece

1554:

1509:

1480:

1467:

1452:

1439:

1426:

1407:

1387:

1359:

1346:

1329:

1316:

1288:

1220:

1197:

1161:

1124:

1112:

906:

897:

880:

863:

854:

845:

1958:Archilochos fragments in Greek

1863:. Cambridge University Press.

1071:

1055:

962:

924:

828:

504:

259:Archaeological Museum of Paros

1:

1477:1.472–474; 16.182–183; 18.493

918:

563:, with a resounding refrain,

161:

84:

67:

45:

1948:Web Resources on Archilochos

1587:Barron & Easterling 1985

1549:Barron & Easterling 1985

1504:Barron & Easterling 1985

1382:Barron & Easterling 1985

1311:Barron & Easterling 1985

1050:Barron & Easterling 1985

1000:Barron & Easterling 1985

791:, in which Achaeans battled

179:

7:

1878:Gerber, Douglas E. (1999).

1831:. Bristol Classical Press.

1825:Campbell, David A. (1982).

57:

10:

2050:

2019:7th-century BC Greek poets

1203:Gerber, Douglas E., 1997,

710:

706:

670:

565:

499:

406:

402:

153:

18:

1953:The Poetry of Archilochos

1749:"POxy Oxyrhynchus Online"

1698:The Songs of Aristophanes

948:10.1017/S0009838800027531

599:

463:

417:I am the servant of Lord

96:

80:

63:

53:

37:

30:

1599:Diane J., Rayor (1991).

1581:p. 57, Scholiast on Ar.

822:

655:

366:The inscriptions in the

1753:www.papyrology.ox.ac.uk

1696:L.P.E. Parker, (1997),

1515:Davenport, Guy (1980),

1337:Exhortation to learning

1081:3.17.1418b28, cited by

164:680 – c. 645 BC) was a

1589:, p. 129 (note 1)

805:The Oxyrhynchus Papyri

761:

752:Reception and editions

616:

583:

495:

486:

461:

355:

261:

201:

1906:. Walter de Gruyter.

1488:Principles of Oratory

1322:Fragment 114, trans.

1063:The Classical Journal

759:

581:χαῖρ' ἄναξ Ἡράκλεες.

571:

491:

482:

454:

349:

274:Clement of Alexandria

256:

187:

1473:See for example the

770:Poetae Lyrici Graeci

575:χαῖρ' ἄναξ Ἡράκλεες,

391:The poet's character

2004:Ancient Greek poets

1880:Greek Iambic Poetry

1855:Knox, Bernard M. W.

1687:22.98–99 and 22.122

1666:, pp. 153–154.

1635:Fragment 5, trans.

1551:, pp. 120–121.

1458:Jeffrey M. Hurwit,

1369:10: 117–163, Geneva

1352:Fragment 1, trans.

1170:, p. 145, n. 1

936:Classical Quarterly

873:is a promontory on

813:Old Assyrian Empire

664:(as for example in

618:One of the Saians (

326:, showed Tellis in

172:from the island of

1932:Works by or about

1828:Greek Lyric Poetry

1400:10.520a-b, trans.

892:Palatine Anthology

803:and published in

801:Oxyrhynchus Papyri

762:

662:dactylic hexameter

573:Τήνελλα καλλίνικε,

509:Strasbourg papyrus

356:

303:Palatine Anthology

262:

202:

188:Coin from ancient

21:Archilochus (bird)

2009:Ionic Greek poets

1913:978-3-11-083318-8

1870:978-0-521-35981-8

1851:Easterling, P. E.

1838:978-0-86292-008-1

1817:978-90-04-09944-9

1610:978-0-520-07336-4

1300:978-0-415-97334-2

1146:, pp. 45–46.

1109:, pp. 43–44.

1097:, pp. 22–39.

983:978-0-7139-9980-8

749:

748:

638:

637:

579:Τήνελλα καλλίνικε

566:Τήνελλα καλλίνικε

428:

427:

104:

103:

2041:

1931:

1917:

1893:

1874:

1842:

1821:

1792:

1791:

1763:

1757:

1756:

1745:

1739:

1732:

1726:

1720:

1714:

1707:

1701:

1694:

1688:

1673:

1667:

1661:

1652:

1646:

1640:

1639:, pp. 80–82

1633:

1627:

1621:

1615:

1614:

1596:

1590:

1571:

1565:

1558:

1552:

1546:

1540:

1534:

1528:

1513:

1507:

1501:

1495:

1490:10.1.60, trans.

1484:

1478:

1471:

1465:

1456:

1450:

1443:

1437:

1430:

1424:

1411:

1405:

1391:

1385:

1379:

1370:

1367:Entretiens Hardt

1363:

1357:

1350:

1344:

1333:

1327:

1320:

1314:

1308:

1302:

1292:

1286:

1280:

1267:

1261:

1255:

1249:

1243:

1237:

1231:

1224:

1218:

1201:

1195:

1189:

1183:

1177:

1171:

1165:

1159:

1153:

1147:

1141:

1135:

1128:

1122:

1121:, pp. 16–33

1116:

1110:

1104:

1098:

1092:

1086:

1085:, pp. 93–95

1075:

1069:

1059:

1053:

1047:

1036:

1030:

1024:

1018:

1003:

997:

988:

987:

966:

960:

959:

928:

913:

910:

904:

901:

895:

884:

878:

871:heights of Gyrae

867:

861:

858:

852:

849:

843:

832:

725:

724:

699:

698:

673:

672:

632:

626:

611:

605:

596:

568:

567:

549:nine lyric poets

502:

501:

445:Valerius Maximus

443:). According to

411:

410:

395:

394:

379:over 800 years.

298:Aelius Aristides

166:Greek lyric poet

163:

156:

155:

146:

145:

142:

141:

138:

135:

132:

129:

126:

123:

120:

117:

89:

86:

72:

69:

47:

42:

28:

27:

2049:

2048:

2044:

2043:

2042:

2040:

2039:

2038:

2029:Ancient Parians

1984:

1983:

1924:

1914:

1898:West, Martin L.

1890:

1871:

1839:

1818:

1800:

1795:

1764:

1760:

1747:

1746:

1742:

1733:

1729:

1721:

1717:

1708:

1704:

1700:, Oxford, p. 36

1695:

1691:

1674:

1670:

1662:

1655:

1647:

1643:

1634:

1630:

1622:

1618:

1611:

1597:

1593:

1572:

1568:

1559:

1555:

1547:

1543:

1535:

1531:

1514:

1510:

1502:

1498:

1485:

1481:

1472:

1468:

1457:

1453:

1444:

1440:

1431:

1427:

1412:

1408:

1392:

1388:

1380:

1373:

1364:

1360:

1351:

1347:

1334:

1330:

1321:

1317:

1309:

1305:

1293:

1289:

1281:

1270:

1262:

1258:

1250:

1246:

1238:

1234:

1225:

1221:

1202:

1198:

1190:

1186:

1178:

1174:

1166:

1162:

1154:

1150:

1142:

1138:

1129:

1125:

1117:

1113:

1105:

1101:

1093:

1089:

1076:

1072:

1068:.1:1–15, p. 14.

1060:

1056:

1048:

1039:

1031:

1027:

1019:

1006:

998:

991:

984:

967:

963:

942:(3–4): 97–109.

929:

925:

921:

916:

911:

907:

902:

898:

885:

881:

868:

864:

859:

855:

850:

846:

833:

829:

825:

754:

744:

742:

740:

738:

736:

734:

732:

726:

722:

720:

718:

716:

714:

712:

678:(four pairs of

658:

634:

630:

629:

627:

624:

623:

613:

609:

608:

606:

603:

602:

580:

578:

576:

574:

466:

422:

412:

408:

393:

318:by the Thasian

182:

114:

110:

91:

87:

73:

70:

59:

49:

33:

24:

17:

12:

11:

5:

2047:

2037:

2036:

2031:

2026:

2024:Ancient Thasos

2021:

2016:

2011:

2006:

2001:

1999:640s BC deaths

1996:

1994:680s BC births

1982:

1981:

1975:

1970:

1965:

1960:

1955:

1950:

1945:

1940:

1923:

1922:External links

1920:

1919:

1918:

1912:

1894:

1888:

1875:

1869:

1843:

1837:

1822:

1816:

1799:

1796:

1794:

1793:

1780:10.2307/311017

1758:

1740:

1727:

1715:

1702:

1689:

1668:

1653:

1651:, p. 145.

1641:

1628:

1616:

1609:

1591:

1585:217, cited by

1566:

1553:

1541:

1529:

1508:

1506:, p. 123.

1496:

1479:

1466:

1451:

1438:

1425:

1406:

1398:de curiositate

1386:

1384:, p. 119.

1371:

1358:

1345:

1328:

1315:

1313:, p. 121.

1303:

1287:

1285:, p. 138.

1268:

1256:

1244:

1232:

1219:

1196:

1184:

1182:, p. 150.

1172:

1160:

1148:

1136:

1130:translated by

1123:

1111:

1099:

1087:

1070:

1054:

1052:, p. 118.

1037:

1025:

1023:, p. 136.

1004:

1002:, p. 117.

989:

982:

961:

922:

920:

917:

915:

914:

905:

896:

879:

862:

853:

844:

840:Robin Lane Fox

826:

824:

821:

817:Shamshi-Adad I

753:

750:

747:

746:

728:

705:

704:

702:

657:

654:

636:

635:

620:Thracian tribe

614:

465:

462:

458:Dio Chrysostom

426:

425:

414:

401:

400:

398:

392:

389:

294:Dio Chrysostom

213:, the king of

181:

178:

170:Archaic period

102:

101:

98:

94:

93:

82:

78:

77:

65:

61:

60:

55:

51:

50:

43:

35:

34:

31:

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

2046:

2035:

2032:

2030:

2027:

2025:

2022:

2020:

2017:

2015:

2012:

2010:

2007:

2005:

2002:

2000:

1997:

1995:

1992:

1991:

1989:

1979:

1976:

1974:

1971:

1969:

1966:

1964:

1961:

1959:

1956:

1954:

1951:

1949:

1946:

1944:

1941:

1939:

1935:

1930:

1926:

1925:

1915:

1909:

1905:

1904:

1899:

1895:

1891:

1889:9780674995819

1885:

1881:

1876:

1872:

1866:

1862:

1861:

1856:

1852:

1848:

1847:Barron, J. P.

1844:

1840:

1834:

1830:

1829:

1823:

1819:

1813:

1809:

1808:

1802:

1801:

1789:

1785:

1781:

1777:

1773:

1769:

1762:

1754:

1750:

1744:

1737:

1731:

1724:

1719:

1713:, p. 167

1712:

1706:

1699:

1693:

1686:

1685:

1680:

1679:

1672:

1665:

1664:Campbell 1982

1660:

1658:

1650:

1649:Campbell 1982

1645:

1638:

1632:

1626:, p. 49.

1625:

1620:

1612:

1606:

1602:

1595:

1588:

1584:

1580:

1576:

1570:

1563:

1557:

1550:

1545:

1538:

1533:

1526:

1525:0-520-05223-4

1522:

1518:

1512:

1505:

1500:

1493:

1489:

1483:

1476:

1470:

1463:

1462:

1455:

1448:

1442:

1435:

1429:

1422:

1418:

1415:

1410:

1403:

1399:

1395:

1390:

1383:

1378:

1376:

1368:

1362:

1355:

1349:

1342:

1338:

1332:

1326:, p. 153

1325:

1319:

1312:

1307:

1301:

1297:

1291:

1284:

1283:Campbell 1982

1279:

1277:

1275:

1273:

1266:, p. 46.

1265:

1260:

1254:, p. 59.

1253:

1248:

1242:, p. 27.

1241:

1236:

1229:

1223:

1216:

1215:90-04-09944-1

1212:

1208:

1207:

1200:

1194:, p. 75.

1193:

1188:

1181:

1180:Campbell 1982

1176:

1169:

1164:

1158:, p. 28.

1157:

1152:

1145:

1140:

1133:

1127:

1120:

1115:

1108:

1103:

1096:

1091:

1084:

1080:

1074:

1067:

1064:

1058:

1051:

1046:

1044:

1042:

1035:, p. 43.

1034:

1029:

1022:

1021:Campbell 1982

1017:

1015:

1013:

1011:

1009:

1001:

996:

994:

985:

979:

975:

971:

965:

957:

953:

949:

945:

941:

937:

933:

932:Jacoby, Felix

927:

923:

909:

900:

893:

888:

883:

876:

872:

866:

857:

848:

841:

837:

831:

827:

820:

818:

814:

810:

806:

802:

798:

794:

790:

786:

781:

779:

778:André Bonnard

775:

771:

767:

766:Theodor Bergk

758:

745:

729:

727:

707:

700:

697:

695:

694:

689:

685:

681:

677:

667:

663:

653:

651:

647:

643:

633:

621:

615:

612:

598:

597:

594:

592:

588:

582:

570:

562:

561:Olympic Games

558:

554:

550:

546:

542:

538:

534:

530:

526:

523:, along with

522:

517:

514:

510:

506:

494:

490:

485:

481:

479:

474:

471:

460:

459:

453:

450:

446:

442:

438:

432:

424:

420:

415:

413:

403:

396:

388:

386:

380:

378:

374:

369:

368:Archilocheion

364:

362:

353:

348:

344:

341:

337:

336:Archilocheion

333:

329:

325:

321:

317:

313:

309:

305:

304:

299:

295:

291:

287:

283:

279:

275:

271:

267:

260:

255:

251:

249:

245:

240:

236:

235:Archilocheion

231:

228:

222:

220:

216:

212:

208:

199:

195:

191:

186:

177:

175:

171:

167:

159:

150:

144:

108:

99:

95:

88: 645 BC

83:

79:

76:

71: 680 BC

66:

62:

56:

52:

41:

36:

29:

26:

22:

2014:Iambic poets

1902:

1879:

1859:

1827:

1806:

1798:Bibliography

1771:

1767:

1761:

1752:

1743:

1735:

1730:

1722:

1718:

1705:

1697:

1692:

1682:

1676:

1671:

1644:

1631:

1619:

1600:

1594:

1582:

1578:

1574:

1569:

1561:

1556:

1544:

1539:, p. 6.

1532:

1516:

1511:

1499:

1494:, p. 65

1487:

1486:Quintilian,

1482:

1474:

1469:

1459:

1454:

1449:, p. 43

1441:

1436:, p. 39

1428:

1423:, p. 39

1409:

1404:, p. 63

1397:

1389:

1366:

1361:

1356:, p. 77

1348:

1343:, p. 41

1336:

1331:

1318:

1306:

1290:

1259:

1247:

1235:

1230:, p. 49

1222:

1205:

1199:

1187:

1175:

1163:

1151:

1139:

1134:, p. 75

1126:

1114:

1102:

1090:

1078:

1073:

1065:

1062:

1057:

1028:

973:

964:

939:

935:

926:

908:

899:

891:

882:

870:

865:

856:

847:

836:Felix Jacoby

830:

804:

782:

773:

769:

763:

730:

708:

691:

688:Aristophanes

683:

659:

639:

619:

617:

600:

584:

572:

521:iambic poets

518:

496:

492:

487:

483:

467:

455:

433:

429:

416:

404:

381:

367:

365:

357:

335:

301:

263:

234:

232:

223:

203:

157:

106:

105:

90:(aged c. 35)

25:

1934:Archilochus

1711:Gerber 1999

1637:Gerber 1999

1537:Gerber 1999

1492:Gerber 1999

1447:Gerber 1999

1434:Gerber 1999

1421:Gerber 1999

1402:Gerber 1999

1354:Gerber 1999

1341:Gerber 1999

1324:Gerber 1999

1228:Gerber 1999

1192:Gerber 1999

1168:Gerber 1999

1132:Gerber 1999

1119:Gerber 1999

1083:Gerber 1999

693:The Knights

158:Arkhílokhos

107:Archilochus

54:Native name

32:Archilochus

1988:Categories

1938:Wikisource

1681:20.18 ff,

1624:Brown 1997

1264:Brown 1997

1252:Brown 1997

1217:. cf. p.50

1144:Brown 1997

1107:Brown 1997

1077:Aristotle

1033:Brown 1997

919:References

789:Trojan War

676:catalectic

545:lyric poet

478:Quintilian

375:lasted on

352:Heraclitus

330:, sharing

320:Polygnotus

239:orthostats

97:Occupation

1810:. Brill.

1575:ap. Orion

1339:, trans.

1240:West 1974

1209:, Brill.

1156:West 1974

1095:West 1974

970:Fox, R.L.

956:170382248

525:Semonides

505:Biography

473:hexameter

373:hero cult

324:Pausanias

207:Aristotle

180:Biography

154:Ἀρχίλοχος

58:Ἀρχίλοχος

1900:(1974).

1857:(eds.).

1579:Et. Mag.

1573:Didymus

1394:Plutarch

1079:Rhetoric

972:(2008).

809:Akkadian

795:king of

793:Telephus

680:trochees

646:Anacreon

557:Heracles

537:Callinus

533:Tyrtaeus

529:Hipponax

449:Spartans

419:Enyalios

340:Dionysus

286:Plutarch

192:showing

1678:Odyssey

1335:Galen,

1226:trans.

887:Elegies

785:elegiac

684:running

642:Alcaeus

361:Neobule

308:Demeter

270:Proclus

248:archons

168:of the

1910:

1886:

1867:

1835:

1814:

1788:311017

1786:

1774:: 18.

1607:

1527:, p.2.

1523:

1417:α 4112

1298:

1213:

980:

954:

650:Horace

591:Hesiod

500:ἴαμβος

464:Poetry

447:, the

332:Charon

316:Delphi

312:Thasos

282:Aelian

278:Cicero

266:Tatian

244:Delphi

227:Thasos

219:iambus

190:Thasos

1784:JSTOR

1684:Iliad

1583:Birds

1475:Iliad

952:S2CID

894:7.351

875:Tenos

823:Notes

797:Mysia

666:elegy

656:Style

587:Homer

541:elegy

513:aulos

437:below

385:Naxos

377:Paros

328:Hades

290:Galen

215:Lydia

211:Gyges

198:nymph

194:Satyr

174:Paros

149:Greek

92:Paros

75:Paros

1908:ISBN

1884:ISBN

1865:ISBN

1833:ISBN

1812:ISBN

1675:See

1605:ISBN

1521:ISBN

1414:Suda

1296:ISBN

1211:ISBN

978:ISBN

869:The

774:Budé

671:θυμέ

648:and

589:and

553:lyre

535:and

527:and

470:epic

441:Suda

196:and

100:Poet

81:Died

64:Born

1936:at

1776:doi

944:doi

768:in

310:on

116:ɑːr

1990::

1849:;

1782:.

1772:82

1770:.

1751:.

1656:^

1577:,

1396:,

1374:^

1271:^

1066:71

1040:^

1007:^

992:^

950:.

940:35

938:.

815:,

652:.

644:,

480::

296:,

292:,

288:,

284:,

280:,

276:,

272:,

268:,

221:.

162:c.

160:;

151::

147:;

85:c.

68:c.

46:c.

1916:.

1892:.

1873:.

1841:.

1820:.

1790:.

1778::

1755:.

1613:.

986:.

958:.

946::

421:,

143:/

140:s

137:ə

134:k

131:ə

128:l

125:ɪ

122:k

119:ˈ

113:/

109:(

23:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.