201:) held that the stars, Sun, Moon, and planets are all made of fire. But whilst the stars are fastened on a revolving crystal sphere like nails or studs, the Sun, Moon, and planets, and also the Earth, all just ride on air like leaves because of their breadth. And whilst the fixed stars are carried around in a complete circle by the stellar sphere, the Sun, Moon and planets do not revolve under the Earth between setting and rising again like the stars do, but rather on setting they go laterally around the Earth like a cap turning halfway around the head until they rise again. And unlike Anaximander, he relegated the fixed stars to the region most distant from the Earth. The most enduring feature of Anaximenes' cosmos was its conception of the stars being fixed on a crystal sphere as in a rigid frame, which became a fundamental principle of cosmology down to Copernicus and Kepler.

579:

closer to the apparent sense of the Qur'anic verses regarding the celestial orbits." However, al-Razi mentions that some, such as the

Islamic scholar Dahhak, considered them to be abstract. Al-Razi himself, was undecided, he said: "In truth, there is no way to ascertain the characteristics of the heavens except by authority ." Setia concludes: "Thus it seems that for al-Razi (and for others before and after him), astronomical models, whatever their utility or lack thereof for ordering the heavens, are not founded on sound rational proofs, and so no intellectual commitment can be made to them insofar as description and explanation of celestial realities are concerned."

388:

110:, they presumed that each planetary sphere was exactly thick enough to accommodate them. By combining this nested sphere model with astronomical observations, scholars calculated what became generally accepted values at the time for the distances to the Sun: about 4 million miles (6.4 million kilometres), to the other planets, and to the edge of the universe: about 73 million miles (117 million kilometres). The nested sphere model's distances to the Sun and planets differ significantly from modern measurements of the distances, and the

761:'s tabulated distances of the comet of 1577, which passed through the planetary orbs, led Tycho to conclude that "the structure of the heavens was very fluid and simple." Tycho opposed his view to that of "very many modern philosophers" who divided the heavens into "various orbs made of hard and impervious matter." Edward Grant found relatively few believers in hard celestial spheres before Copernicus and concluded that the idea first became common sometime between the publication of Copernicus's

708:

244:

Eudoxus and

Callippus qualitatively describe the major features of the motion of the planets, they fail to account exactly for these motions and therefore cannot provide quantitative predictions. Although historians of Greek science have traditionally considered these models to be merely geometrical representations, recent studies have proposed that they were also intended to be physically real or have withheld judgment, noting the limited evidence to resolve the question.

270:

258:

whereas in the models of

Eudoxus and Callippus each planet's individual set of spheres were not connected to those of the next planet. Aristotle says the exact number of spheres, and hence the number of movers, is to be determined by astronomical investigation, but he added additional spheres to those proposed by Eudoxus and Callippus, to counteract the motion of the outer spheres. Aristotle considers that these spheres are made of an unchanging fifth element, the

36:

821:

487:, he recalculated the distance of the planets using parameters which he redetermined. Taking the distance of the Sun as 1,266 Earth radii, he was forced to place the sphere of Venus above the sphere of the Sun; as a further refinement, he added the planet's diameters to the thickness of their spheres. As a consequence, his version of the nesting spheres model had the sphere of the stars at a distance of 140,177 Earth radii.

375:. In antiquity the order of the lower planets was not universally agreed. Plato and his followers ordered them Moon, Sun, Mercury, Venus, and then followed the standard model for the upper spheres. Others disagreed about the relative place of the spheres of Mercury and Venus: Ptolemy placed both of them beneath the Sun with Venus above Mercury, but noted others placed them both above the Sun; some medieval thinkers, such as

660:

2926:

2890:

2878:

2914:

1001:

2902:

781:, which accounted for the spheres' measured astronomical distance. In Kepler's mature celestial physics, the spheres were regarded as the purely geometric spatial regions containing each planetary orbit rather than as the rotating physical orbs of the earlier Aristotelian celestial physics. The eccentricity of each planet's orbit thereby defined the

681:). Although Copernicus does not treat the physical nature of the spheres in detail, his few allusions make it clear that, like many of his predecessors, he accepted non-solid celestial spheres. Copernicus rejected the ninth and tenth spheres, placed the orb of the Moon around the Earth, and moved the Sun from its orb to the center of the

608:, a historian of science, has provided evidence that medieval scholastic philosophers generally considered the celestial spheres to be solid in the sense of three-dimensional or continuous, but most did not consider them solid in the sense of hard. The consensus was that the celestial spheres were made of some kind of continuous fluid.

412:, used the Ptolemaic model of nesting spheres to compute distances to the stars and planetary spheres. Al-Farghānī's distance to the stars was 20,110 Earth radii which, on the assumption that the radius of the Earth was 3,250 miles (5,230 kilometres), came to 65,357,500 miles (105,182,700 kilometres). An introduction to Ptolemy's

631:

such as motive souls or impressed forces. Most of these models were qualitative, although a few incorporated quantitative analyses that related speed, motive force and resistance. By the end of the Middle Ages, the common opinion in Europe was that celestial bodies were moved by external intelligences, identified with the

877:

1484:

Bk1.10 Copernicus claimed the empirical reason why Plato's followers put the orbits of

Mercury and Venus above the Sun's was that if they were sub-solar, then by the Sun's reflected light they would only ever appear as hemispheres at most and would also sometimes eclipse the Sun, but they do neither.

578:

about whether the celestial spheres are real, concrete physical bodies or "merely the abstract circles in the heavens traced out… by the various stars and planets." Setia points out that most of the learned, and the astronomers, said they were solid spheres "on which the stars turn… and this view is

475:

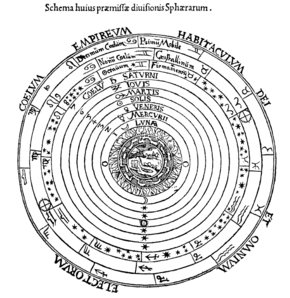

sought to explain the complex motions of the planets without

Ptolemy's epicycles and eccentrics, using an Aristotelian framework of purely concentric spheres that moved with differing speeds from east to west. This model was much less accurate as a predictive astronomical model, but it was discussed

182:

wholly encompassing the Earth, which had disintegrated into many individual rings. Hence, in

Anaximanders's cosmogony, in the beginning was the sphere, out of which celestial rings were formed, from some of which the stellar sphere was in turn composed. As viewed from the Earth, the ring of the Sun

177:

in the early 6th century BC. In his cosmology both the Sun and Moon are circular open vents in tubular rings of fire enclosed in tubes of condensed air; these rings constitute the rims of rotating chariot-like wheels pivoting on the Earth at their centre. The fixed stars are also open vents in such

331:

embedded in the deferent, with the planet embedded in the epicyclical sphere/slice. Ptolemy's model of nesting spheres provided the general dimensions of the cosmos, the greatest distance of Saturn being 19,865 times the radius of the Earth and the distance of the fixed stars being at least 20,000

630:

Medieval astronomers and philosophers developed diverse theories about the causes of the celestial spheres' motions. They attempted to explain the spheres' motions in terms of the materials of which they were thought to be made, external movers such as celestial intelligences, and internal movers

243:

modified this system, using five spheres for his models of the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, and Mars and retaining four spheres for the models of

Jupiter and Saturn, thus making 33 spheres in all. Each planet is attached to the innermost of its own particular set of spheres. Although the models of

105:

are viewed as the paths of those planets through mostly empty space. Ancient and medieval thinkers, however, considered the celestial orbs to be thick spheres of rarefied matter nested one within the other, each one in complete contact with the sphere above it and the sphere below. When scholars

942:

vividly portrays the celestial spheres as a "great machine of the universe" constructed by God. The explorer Vasco da Gama is shown the celestial spheres in the form of a mechanical model. Contrary to Cicero's representation, da Gama's tour of the spheres begins with the

Empyrean, then descends

257:

developed a physical cosmology of spheres, based on the mathematical models of

Eudoxus. In Aristotle's fully developed celestial model, the spherical Earth is at the centre of the universe and the planets are moved by either 47 or 55 interconnected spheres that form a unified planetary system,

929:, employed the same motif. He drew the spheres in the conventional order, with the Moon closest to the Earth and the stars highest, but the spheres were concave upwards, centered on God, rather than concave downwards, centered on the Earth. Below this figure Oresme quotes the

222:

proposed that the body of the cosmos was made in the most perfect and uniform shape, that of a sphere containing the fixed stars. But it posited that the planets were spherical bodies set in rotating bands or rings rather than wheel rims as in

Anaximander's cosmology.

776:

considered the distances of the planets and the consequent gaps required between the planetary spheres implied by the Copernican system, which had been noted by his former teacher, Michael Maestlin. Kepler's Platonic cosmology filled the large gaps with the five

319:, his geometrical model achieved greater mathematical detail and predictive accuracy than had been exhibited by earlier concentric spherical models of the cosmos. In Ptolemy's physical model, each planet is contained in two or more spheres, but in Book 2 of his

121:

Albert Van Helden has suggested that from about 1250 until the 17th century, virtually all educated Europeans were familiar with the Ptolemaic model of "nesting spheres and the cosmic dimensions derived from it". Even following the adoption of Copernicus's

685:. The planetary orbs circled the center of the universe in the following order: Mercury, Venus, the great orb containing the Earth and the orb of the Moon, then the orbs of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Finally he retained the eighth sphere of the

623:, which maintained that all physical effects were caused directly by God's will rather than by natural causes. He maintained that the celestial spheres were "imaginary things" and "more tenuous than a spider's web". His views were challenged by

494:

began to address the implications of the rediscovered philosophy of Aristotle and astronomy of Ptolemy. Both astronomical scholars and popular writers considered the implications of the nested sphere model for the dimensions of the universe.

363:. In more detailed models the seven planetary spheres contained other secondary spheres within them. The planetary spheres were followed by the stellar sphere containing the fixed stars; other scholars added a ninth sphere to account for the

888:

Some late medieval figures noted that the celestial spheres' physical order was inverse to their order on the spiritual plane, where God was at the center and the Earth at the periphery. Near the beginning of the fourteenth century

434:

presented independent calculations of the distances to the planets on the model of nesting spheres, which he thought was due to scholars writing after Ptolemy. His calculations yielded a distance of 19,000 Earth radii to the stars.

554:, that it would take 8,000 years to reach the highest starry heaven. General understanding of the dimensions of the universe derived from the nested sphere model reached wider audiences through the presentations in Hebrew by

178:

wheel rims, but there are so many such wheels for the stars that their contiguous rims all together form a continuous spherical shell encompassing the Earth. All these wheel rims had originally been formed out of an original

789:, the cause of planetary motion became the rotating Sun, itself rotated by its own motive soul. However, an immobile stellar sphere was a lasting remnant of physical celestial spheres in Kepler's cosmology.

126:

of the universe, new versions of the celestial sphere model were introduced, with the planetary spheres following this sequence from the central Sun: Mercury, Venus, Earth-Moon, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn.

570:

Philosophers were less concerned with such mathematical calculations than with the nature of the celestial spheres, their relation to revealed accounts of created nature, and the causes of their motion.

704:, and the Moon, and expanding the sphere of stars infinitely to encompass all the stars and also to serve as "the court of the Great God, the habitacle of the elect, and of the coelestiall angelles."

98:), like gems set in orbs. Since it was believed that the fixed stars did not change their positions relative to one another, it was argued that they must be on the surface of a single starry sphere.

2849:

751:

indicated that the comet was beyond Saturn, while the absence of observed refraction indicated the celestial region was of the same material as air, hence there were no planetary spheres.

627:(1339–1413), who maintained that even if the celestial spheres "do not have an external reality, yet they are things that are correctly imagined and correspond to what in actuality".

651:, who was identified with God. Each of the lower spheres was moved by a subordinate spiritual mover (a replacement for Aristotle's multiple divine movers), called an intelligence.

431:

138:

continued to discuss celestial spheres, although he did not consider that the planets were carried by the spheres but held that they moved in elliptical paths described by

527:

cited Al-Farghānī's distance to the stars of 20,110 Earth radii, or 65,357,700 miles (105,183,000 km), from which he computed the circumference of the universe to be

239:

for all the planets, with three spheres each for his models of the Moon and the Sun and four each for the models of the other five planets, thus making 26 spheres in all.

454:, al-Haytham's presentation differs in sufficient detail that it has been argued that it reflects an independent development of the concept. In chapters 15–16 of his

943:

inward toward Earth, culminating in a survey of the domains and divisions of earthly kingdoms, thus magnifying the importance of human deeds in the divine plan.

869:, which included a discussion of the various schools of thought on the order of the spheres, did much to spread the idea of the celestial spheres through the

2000:(Frankfurt a. d. Oder, 1576), quoted in Peter Barker and Bernard R. Goldstein, "Realism and Instrumentalism in Sixteenth Century Astronomy: A Reappraisal",

909:

Heaven, where he comes face to face with God himself and is granted understanding of both divine and human nature. Later in the century, the illuminator of

2958:

861:

describes an ascent through the celestial spheres, compared to which the Earth and the Roman Empire dwindle into insignificance. A commentary on the

307:(fl. c. 150 AD) developed geometrical predictive models of the motions of the stars and planets and extended them to a unified physical model of the

409:

335:

The planetary spheres were arranged outwards from the spherical, stationary Earth at the centre of the universe in this order: the spheres of the

671:

drastically reformed the model of astronomy by displacing the Earth from its central place in favour of the Sun, yet he called his great work

2784:

The General History of Astronomy: Volume 2 Planetary astronomy from the Renaissance to the rise of astrophysics Part A Tycho Brahe to Newton

503:, used the model of nesting spheres to compute the distances of the various planets from the Earth, which he gave as 22,612 Earth radii or

700:(1576). Here he arranged the "orbes" in the new Copernican order, expanding one sphere to carry "the globe of mortalitye", the Earth, the

541:

miles (661,148,316.1 km). Clear evidence that this model was thought to represent physical reality is the accounts found in Bacon's

799:"Because the medieval universe is finite, it has a shape, the perfect spherical shape, containing within itself an ordered variety....

801:"The spheres ... present us with an object in which the mind can rest, overwhelming in its greatness but satisfying in its harmony."

2852:

3229:

2258:

Duhem, Pierre. "History of Physics." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 18 Jun. 2008 <

143:

3433:

3461:

2951:

2813:

2701:

2602:

2567:

2519:

2330:

2305:

2249:

1859:

963:

142:. In the late 1600s, Greek and medieval theories concerning the motion of terrestrial and celestial objects were replaced by

139:

3423:

3219:

2839:

711:

Johannes Kepler's diagram of the celestial spheres, and of the spaces between them, following the opinion of Copernicus (

673:

2975:

2747:

2684:

2667:

2638:

2623:

2585:

2550:

2499:

2418:

2404:

2390:

2365:

2348:

2285:

2144:

1507:

1040:

159:

94:

are accounted for by treating them as embedded in rotating spheres made of an aetherial, transparent fifth element (

3456:

2944:

757:'s investigations of a series of comets from 1577 to 1585, aided by Rothmann's discussion of the comet of 1585 and

1011:

701:

2530:

2126:

transl. by William Harris Stahl, New York: Columbia Univ. Pr., 1952; on the order of the spheres see pp. 162–165.

905:, described God as a light at the center of the cosmos. Here the poet ascends beyond physical existence to the

480:

232:

3356:

2653:

At the Threshold of Exact Science: Selected Writings of Annaliese Maier on Late Medieval Natural Philosophy

1317:"The final cause, then, produces motion by being loved, but all other things move by being moved" Aristotle

2039:

Bernard R. Goldstein and Peter Barker, "The Role of Rothmann in the Dissolution of the Celestial Spheres",

1410:

1406:

364:

2171:

edited and translated by A, D. Menut and A. J. Denomy, Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Pr., 1968, pp. 282–283.

3466:

786:

624:

574:

Adi Setia describes the debate among Islamic scholars in the twelfth century, based on the commentary of

439:

582:

Christian and Muslim philosophers modified Ptolemy's system to include an unmoved outermost region, the

2868:

1847:

259:

95:

1879:

3153:

648:

372:

323:

Ptolemy depicted thick circular slices rather than spheres as in its Book 1. One sphere/slice is the

115:

615:

Adud al-Din al-Iji (1281–1355) rejected the principle of uniform and circular motion, following the

26:"Heavenly spheres" redirects here. For the album by the Studio de musique ancienne de Montréal, see

2629:

Lloyd, G. E. R., "Heavenly aberrations: Aristotle the amateur astronomer," pp. 160–183 in his

1018:

1758:

3148:

2967:

550:

368:

249:

3295:

3168:

3103:

1851:

953:

3331:

3260:

2998:

2767:

1390:

1349:

491:

472:

187:

131:

1839:

1759:"Fakhr Al-Din Al-Razi on Physics and the Nature of the Physical World: A Preliminary Survey"

719:

In the sixteenth century, a number of philosophers, theologians, and astronomers—among them

3402:

3143:

3093:

3013:

2988:

2433:

1891:

720:

575:

387:

111:

216:

all held that the universe was spherical. And much later in the fourth century BC Plato's

150:, which explain how Kepler's laws arise from the gravitational attraction between bodies.

8:

3173:

3078:

3028:

3003:

2930:

2295:

926:

811:

668:

443:

286:

147:

2437:

2274:

Medieval Cosmology: Theories of Infinity, Place, Time, Void, and the Plurality of Worlds

1895:

1502:, 7.159–65, trans. Bernard R. Goldstein, vol. 1, pp. 123–5. New Haven: Yale Univ. Pr.

590:

and all the elect. Medieval Christians identified the sphere of stars with the Biblical

450:

in terms of nested spheres. Despite the similarity of this concept to that of Ptolemy's

421:

3407:

3321:

2918:

2449:

1923:

1915:

1593:

968:

828:

740:

643:, which moved with the daily motion affecting all subordinate spheres, was moved by an

496:

236:

218:

123:

2505:

743:—abandoned the concept of celestial spheres. Rothmann argued from observations of the

594:

and sometimes posited an invisible layer of water above the firmament, to accord with

3163:

3068:

3023:

2860:

2809:

2743:

2697:

2680:

2663:

2634:

2619:

2598:

2581:

2563:

2557:

2546:

2515:

2495:

2453:

2424:

Grasshoff, Gerd (2012). "Michael Maestlin's Mystery: Theory Building with Diagrams".

2414:

2400:

2386:

2361:

2344:

2326:

2301:

2281:

2245:

2140:

1993:

1927:

1907:

1855:

1840:

1503:

933:

that "The heavens declare the Glory of God and the firmament showeth his handiwork."

870:

728:

424:, presented minor variations of Ptolemy's distances to the celestial spheres. In his

67:

2280:, translated and edited by Roger Ariew, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987

1439:

3428:

3381:

3351:

3341:

3290:

3265:

2894:

2441:

2323:

Ordering the Heavens: Roman Astronomy and Cosmology in the Carolingian Renaissance,

1899:

1585:

1469:

Ordering the Heavens: Roman Astronomy and Cosmology in the Carolingian Renaissance,

895:

858:

758:

555:

447:

340:

91:

27:

20:

2655:, edited by Steven Sargent, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

1440:"The Structure and Function of Ptolemy's Physical Hypotheses of Planetary Motion,"

3376:

3311:

3280:

3178:

3108:

2843:

2691:

2672:

2592:

2509:

2353:

2291:

2239:

2157:

852:

824:

785:

of the inner and outer limits of its celestial sphere and thus its thickness. In

773:

736:

595:

559:

183:

was highest, that of the Moon was lower, and the sphere of the stars was lowest.

135:

2202:, in 'The Basic Works of Aristotle' Richard McKeon (Ed) The Modern Library, 2001

1017:

The references used may be made clearer with a different or consistent style of

832:

3239:

3118:

3053:

3033:

2882:

2611:

2472:. Great Books of the Western World. Vol. 16. Chicago, Ill: William Benton.

2445:

2267:

Le Système du Monde: Histoire des doctrines cosmologiques de Platon à Copernic,

1022:

983:

920:

778:

732:

546:

456:

179:

170:

158:

Further information on the causes of the motions of the celestial spheres:

83:

40:

2836:

2830:

2789:

Thoren, Victor E., "The Comet of 1577 and Tycho Brahe's System of the World,"

2052:

Michael A. Granada, "Did Tycho Eliminate the Celestial Spheres before 1586?",

2026:

Michael A. Granada, "Did Tycho Eliminate the Celestial Spheres before 1586?",

1880:"Freeing Astronomy from Philosophy: An Aspect of Islamic Influence on Science"

102:

3450:

3361:

3346:

3326:

2259:

1911:

978:

973:

958:

910:

901:

837:

693:

644:

640:

327:, with a centre offset somewhat from the Earth; the other sphere/slice is an

263:

2156:

Nicole Oreseme, "Le livre du Ciel et du Monde", 1377, retrieved 2 June 2007.

2137:

The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature,

173:

the ideas of celestial spheres and rings first appeared in the cosmology of

3209:

3058:

2906:

2543:

The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature

1146:

1913/97 Oxford University Press/Sandpiper Books Ltd; see p. 11 of Popper's

724:

707:

605:

2936:

1214:

Neugebauer, History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy, vol. 2, pp. 677–85.

3048:

2993:

2314:

Eastwood, Bruce, "Astronomy in Christian Latin Europe c. 500 – c. 1150,"

938:

806:

754:

524:

483:

proposed a radical change to Ptolemy's system of nesting spheres. In his

379:, placed the sphere of Venus above the Sun and that of Mercury below it.

273:

Ptolemaic model of the spheres for Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn with

269:

262:. Each of these concentric spheres is moved by its own god—an unchanging

174:

130:

Mainstream belief in the theory of celestial spheres did not survive the

87:

2338:

Planetary Diagrams for Roman Astronomy in Medieval Europe, ca. 800–1500,

1576:

Rosen, Edward (1985). "The Dissolution of the Solid Celestial Spheres".

765:

in 1542 and Tycho Brahe's publication of his cometary research in 1588.

460:, Ibn al-Haytham also said that the celestial spheres do not consist of

35:

3366:

3183:

3128:

3088:

3018:

1597:

663:

Thomas Digges' 1576 Copernican heliocentric model of the celestial orbs

636:

616:

612:

519:

468:

376:

213:

209:

205:

79:

1919:

876:

3270:

3123:

3113:

3098:

3043:

3038:

2983:

866:

591:

316:

254:

240:

107:

71:

59:

2806:

Measuring the Universe: Cosmic Dimensions from Aristarchus to Halley

2536:

Great Books of the Western World : 16 Ptolemy Copernicus Kepler

2232:

Great Books of the Western World : 16 Ptolemy Copernicus Kepler

1589:

820:

3371:

3199:

3063:

1903:

906:

748:

682:

583:

328:

324:

299:

278:

274:

659:

266:, and who moves its sphere simply by virtue of being loved by it.

3275:

3138:

3133:

3083:

3073:

2241:

Theories of the World from Antiquity to the Copernican Revolution

620:

356:

304:

75:

2761:

The Philosophy of the Commentators, 200–600 AD: Volume 2 Physics

3386:

3336:

3285:

3158:

3008:

2831:

Working model and complete explanation of the Eudoxus's Spheres

1616:. Vol. 1. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 40–5.

1274:

Larry Wright, "The Astronomy of Eudoxus: Geometry or Physics,"

1184:

For Xenophanes' and Parmenides' spherist cosmologies see Heath

930:

847:

782:

696:, delineated the spheres of the new cosmological system in his

599:

360:

308:

282:

408:

A series of astronomers, beginning with the Muslim astronomer

1979:

Nicholas Jardine, "The Significance of the Copernican Orbs",

1890:(Science in Theistic Contexts: Cognitive Dimensions): 55–57.

1487:

Great Books of the Western World 16 Ptolemy–Copernicus–Kepler

890:

744:

632:

586:

heaven, which came to be identified as the dwelling place of

461:

344:

63:

2594:

From Eudoxus to Einstein—A History of Mathematical Astronomy

2184:, translated by Landeg White. Oxford University Press, 2010.

1842:

The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China, and the West

565:

2468:

Hutchins, Robert Maynard; Adler, Mortimer J., eds. (1952).

2383:

The Scientific Enterprise in Antiquity and the Middle Ages,

686:

392:

352:

336:

2901:

2377:

Grant, Edward, "Celestial Orbs in the Latin Middle Ages,"

545:

of the time needed to walk to the Moon and in the popular

2397:

Planets, Stars, and Orbs: The Medieval Cosmos, 1200–1687,

1998:

Propositiones Cosmographicae de Globi Terreni Dimensione,

587:

426:

348:

2618:

pp. 133–153, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1968.

114:

is now known to be inconceivably large and continuously

2693:

Early Physics and Astronomy: A Historical Introduction

2381:

78(1987): 153–73; reprinted in Michael H. Shank, ed.,

2297:

History of the Planetary Systems from Thales to Kepler

1543:

1541:

1421:

1419:

231:

Instead of bands, Plato's student Eudoxus developed a

2866:

226:

164:

2754:

Philoponus and the Rejection of Aristotelian Science

2480:

Oxford University Press/Sandpiper Books Ltd. 1913/97

2411:

The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages

2808:. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

2616:

Aristotle: The Growth and Structure of his Thought,

2341:

Transactions of the American Philosophical Society,

1538:

1454:Francis R. Johnson, "Marlowe's "Imperiall Heaven,"

1416:

371:, and even an eleventh to account for the changing

2660:Astronomies and Cultures in Early Medieval Europe,

2555:

1563:Ibn al Haytham's on the Configuration of the World

1073:

1071:

792:

558:, in French by Gossuin of Metz, and in Italian by

2848:Henry Mendell, Vignettes of Ancient Mathematics:

2791:Archives Internationales d'Histoire des Sciences,

1188:chapter 7 and chapter 9 respectively, and Popper

919:, a translation of and commentary on Aristotle's

3448:

476:by later European astronomers and philosophers.

2863:– Depiction of celestial spheres in a 1613 book

1565:. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 11–25.

1222:

1220:

1068:

391:The Earth within seven celestial spheres, from

2837:Animated Ptolemaic model of the nested spheres

2545:, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1964

2511:From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe

2139:Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1964, p. 116.

2041:The British Journal for the History of Science

1877:

2952:

2113:, vol. 1, book 4.2.3, pp. 514–15 (1630).

884:Paris, BnF, Manuscrits, Fr. 565, f. 69 (1377)

698:Perfit Description of the Caelestiall Orbes …

82:, and others. In these celestial models, the

2733:The Tychonic and Semi-Tychonic World Systems

2677:A History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy,

1308:Richard McKeon, ed., The Modern Library 2001

1276:Studies in History and Philosophy of Science

1217:

914:

2966:

679:On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres

403:

2959:

2945:

2590:

2360:. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1988

2260:http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12047a.htm

2228:On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres

1614:Al-Bitrūjī: On the Principles of Astronomy

1560:

1377:

1332:History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy,

1237:History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy,

490:About the same time, scholars in European

2772:Translator's Introduction to the Almagest

2696:. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

2597:. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

2494:(translator Mepham) Harvester Press 1977

2423:

2413:, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1996.

2237:

2065:Grant, "Celestial Orbs," pp. 185–86.

1756:

1611:

1427:History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy

1396:Translator's Introduction to the Almagest

1362:

1041:Learn how and when to remove this message

566:Philosophical and theological discussions

479:In the thirteenth century the astronomer

467:Near the end of the twelfth century, the

2562:. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

2244:. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc.

2087:Grasshoff, "Michael Maestlin's Mystery".

1878:Ragep, F. Jamil; Al-Qushji, Ali (2001).

1873:

1871:

1831:

1287:G. E. R. Lloyd, "Saving the Phenomena,"

875:

819:

706:

658:

386:

268:

34:

2207:Science of Mechanics in the Middle Ages

1203:Plato's Cosmology: The Timaeus of Plato

517:miles (118,106,130.55 km). In his

499:'s introductory astronomical text, the

438:Around the turn of the millennium, the

58:, were the fundamental entities of the

3449:

2662:Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1998.

2633:Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1996.

2580:Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Pr., 1978.

2399:Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1994.

2043:, 28 (1995): 385–403, pp. 390–91.

1226:Lloyd, "Heavenly aberrations," p. 173.

936:The late-16th-century Portuguese epic

367:, a tenth to account for the supposed

2940:

2504:

2385:Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Pr., 2000.

2374:, University of California Press 1966

2316:Journal for the History of Astronomy,

2054:Journal for the History of Astronomy,

2028:Journal for the History of Astronomy,

1981:Journal for the History of Astronomy,

1868:

1750:

1575:

1443:Journal for the History of Astronomy,

964:History of the center of the Universe

446:presented a development of Ptolemy's

144:Newton's law of universal gravitation

2786:Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1989

2766:

2726:The Physical World of Late Antiquity

2679:3 vols., New York: Springer, 1975.

2464:, American Institute of Physics 1993

2426:Journal for the History of Astronomy

2343:vol. 94, pt. 3, Philadelphia, 2004.

2167:Ps. 18: 2; quoted in Nicole Oresme,

2004:6.3 (1998): 232–58, pp. 242–23.

1837:

1395:

994:

16:Elements of some cosmological models

2538:, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 1952

2336:Eastwood, Bruce and Gerd Graßhoff,

2216:University of California Press 1999

2056:37 (2006): 126–45, pp. 132–38.

2030:37 (2006): 126–45, pp. 127–29.

1983:13 (1982): 168–94, pp. 177–78.

831:gaze upon the highest Heaven; from

674:De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

13:

2861:M. Blundevile his exercises, p 282

2775:

2689:

2467:

2209:University of Wisconsin Press 1959

2124:Commentary on the Dream of Scipio,

1345:

747:of 1585 that the lack of observed

689:, which he held to be stationary.

227:Emergence of the planetary spheres

165:Early ideas of spheres and circles

14:

3478:

2824:

2782:R. Taton & C. Wilson (eds.),

2559:The Beginnings of Western Science

2485:The contemporaries of Tycho Brahe

2221:The Cambridge Companion to Newton

186:Following Anaximander, his pupil

160:Dynamics of the celestial spheres

140:Kepler's laws of planetary motion

2924:

2912:

2900:

2888:

2876:

2735:in Taton & Wilson (eds) 1989

2728:Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962

2290:

2234:Encyclopædia Britannica Inc 1952

1402:History of the Planetary Systems

1401:

1250:History of the Planetary Systems

999:

598:. An outer sphere, inhabited by

2591:Linton, Christopher M. (2004).

2531:Epitome of Copernican Astronomy

2487:in Taton & Wilson (eds)1989

2269:10 vols., Paris: Hermann, 1959.

2191:

2174:

2161:

2150:

2129:

2116:

2111:Epitome of Copernican Astronomy

2103:

2090:

2081:

2068:

2059:

2046:

2033:

2020:

2007:

1986:

1973:

1960:

1947:

1934:

1818:

1805:

1792:

1779:

1737:

1724:

1711:

1698:

1685:

1672:

1659:

1646:

1633:

1620:

1605:

1578:Journal of the History of Ideas

1569:

1554:

1525:

1512:

1492:

1474:

1471:(Leiden: Brill) 2007, pp. 36–45

1461:

1448:

1432:

1384:

1369:

1354:

1337:

1324:

1311:

1304:1073b1–1074a13, pp. 882–883 in

1294:

1281:

1268:

1255:

1242:

1229:

1208:

1195:

1178:

793:Literary and visual expressions

667:Early in the sixteenth century

2803:

2534:(Bks 4 & 5), published in

2358:Kepler's geometrical cosmology

2212:Cohen, I.B. & Whitman, A.

1612:Goldstein, Bernard R. (1971).

1500:On the Principles of Astronomy

1291:28 (1978): 202–222, at p. 219.

1172:See chapter 5 of Heath’s 1913

1166:

1153:

1136:

1123:

1110:

1097:

1084:

1055:

925:produced for Oresme's patron,

654:

382:

39:Geocentric celestial spheres;

1:

3357:Inferior and superior planets

2169:Le livre du ciel et du monde,

1813:Beginnings of Western Science

1800:Beginnings of Western Science

1079:Beginnings of Western Science

882:Le livre du Ciel et du Monde,

602:, appeared in some accounts.

191:

3462:Early scientific cosmologies

2098:Kepler's geometric cosmology

1561:Langermann, Y. Tzvi (1990).

1306:The Basic Works of Aristotle

916:Le livre du Ciel et du Monde

787:Kepler's celestial mechanics

420:, believed to be written by

369:trepidation of the equinoxes

7:

2804:Van Helden, Albert (1985).

2756:London & Ithaca NY 1987

2556:Lindberg, David C. (1992).

2470:Ptolemy, Copernicus, Kepler

1346:Early Physics and Astronomy

946:

692:The English almanac maker,

365:precession of the equinoxes

10:

3483:

3434:Medieval Islamic astronomy

3231:On the Sizes and Distances

2800:in Taton & Wilson 1989

2719:Three Copernican Treatises

2631:Aristotelian Explorations,

2578:Science in the Middle Ages

2576:Lindberg, David C. (ed.),

2446:10.1177/002182861204300104

2238:Crowe, Michael J. (1990).

1848:Cambridge University Press

611:Later in the century, the

315:. By using eccentrics and

291:Theoricae novae planetarum

157:

153:

25:

18:

3424:Medieval European science

3416:

3395:

3304:

3253:

3192:

3154:Sosigenes the Peripatetic

2974:

2742:London: Duckworth, 1988

2076:Planets, Stars, and Orbs,

1968:Planets, Stars, and Orbs,

1955:Planets, Stars, and Orbs,

1942:Planets, Stars, and Orbs,

1826:Planets, Stars, and Orbs,

1787:Planets, Stars, and Orbs,

1641:Planets, Stars, and Orbs,

1458:, 12 (1945): 35–44, p. 39

1142:See chapter 4 of Heath's

373:obliquity of the ecliptic

2842:8 September 2006 at the

2752:Sorabji, Richard, (ed.)

2740:Matter, Space and Motion

2690:Pederson, Olaf (1993) .

2646:The Science of Mechanics

2300:. New York, NY: Cosimo.

2219:Cohen & Smith (eds)

1667:Planets, Stars, and Orbs

1654:Planets, Stars, and Orbs

1378:From Eudoxus to Einstein

1105:Planets, Stars, and Orbs

1063:Planets, Stars, and Orbs

990:

835:'s illustrations to the

770:Mysterium Cosmographicum

713:Mysterium Cosmographicum

473:al-Bitrūjī (Alpetragius)

444:Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen)

404:Astronomical discussions

19:Not to be confused with

3457:Ancient Greek astronomy

3149:Sosigenes of Alexandria

2968:Ancient Greek astronomy

2776:Hutchins (1952, pp.1–4)

2712:The World of Parmenides

2658:McCluskey, Stephen C.,

2292:Dreyer, John Louis Emil

2002:Perspectives on Science

1148:The World of Parmenides

702:four classical elements

641:outermost moving sphere

551:South English Legendary

101:In modern thought, the

3221:On Sizes and Distances

2768:Taliaferro, R. Catesby

2325:Leiden: Brill, 2007.

1745:Measuring the Universe

1732:Measuring the Universe

1706:Measuring the Universe

1693:Measuring the Universe

1680:Measuring the Universe

1549:Measuring the Universe

1533:Measuring the Universe

1520:Measuring the Universe

1429:, vol. 2, pp. 917–926.

1131:Measuring the Universe

1118:Measuring the Universe

1092:Measuring the Universe

954:Angels in Christianity

915:

885:

843:

842:Canto 28, lines 16–39.

803:

716:

664:

400:

294:

134:. In the early 1600s,

47:

3332:Deferent and epicycle

3261:Antikythera mechanism

2370:Golino, Carlo (ed.),

2226:Copernicus, Nicolaus

2015:From the Closed World

1992:Hilderich von Varel (

1363:Theories of the World

879:

823:

797:

710:

662:

390:

272:

132:Scientific Revolution

103:orbits of the planets

38:

3403:Babylonian astronomy

3094:Hippocrates of Chios

2478:Aristarchus of Samos

2180:Luiz Vaz de Camões,

1289:Classical Quarterly,

1174:Aristarchus of Samos

1144:Aristarchus of Samos

865:by the Roman writer

723:, Andrea Cisalpino,

576:Fakhr al-Din al-Razi

452:Planetary Hypotheses

321:Planetary Hypotheses

313:Planetary hypotheses

264:divine unmoved mover

112:size of the universe

62:models developed by

3174:Theon of Alexandria

2796:Thoren, Victor E.,

2514:. Forgotten Books.

2438:2012JHA....43...57G

2372:Galileo Reappraised

2278:Le Système du Monde

2205:Clagett, Marshall

1896:2001Osir...16...49R

1838:Huff, Toby (2003).

1763:Islam & Science

1719:The Discarded Image

1498:al-Biţrūjī. (1971)

1467:Bruce S. Eastwood,

1366:, pp.45, 49–50, 72,

1278:, 4 (1973): 165–72.

1239:vol. 2, pp. 677–85.

812:The Discarded Image

669:Nicolaus Copernicus

501:Theorica planetarum

399:, late 11th century

287:Georg von Peuerbach

148:Newtonian mechanics

3467:Physical cosmology

3408:Egyptian astronomy

3322:Circle of latitude

2759:Sorabji, Richard,

2738:Sorabji, Richard,

2651:Maier, Annaliese,

2528:Kepler, Johannes,

2490:Koyré, Alexandre,

2318:28(1997): 235–258.

1757:Adi Setia (2004),

969:Musica universalis

886:

844:

779:Platonic polyhedra

741:Christoph Rothmann

735:, Jerónimo Muñoz,

717:

665:

497:Campanus of Novara

401:

295:

237:concentric spheres

204:After Anaximenes,

124:heliocentric model

106:applied Ptolemy's

48:

3442:

3441:

3317:Celestial spheres

2850:Eudoxus of Cnidus

2815:978-0-226-84882-2

2793:29 (1979): 53–67.

2703:978-0-521-40340-5

2604:978-0-521-82750-8

2569:978-0-226-48231-6

2521:978-1-60620-143-5

2462:The Eye of Heaven

2331:978-90-04-16186-3

2321:Eastwood, Bruce,

2307:978-1-60206-441-6

2251:978-0-486-26173-7

2109:Johannes Kepler,

2017:, pp. 28–30.

1861:978-0-521-52994-5

1482:De Revolutionibus

1438:Andrea Murschel,

1252:, pp. 90–1, 121–2

1192:Essays 2 & 3.

1051:

1050:

1043:

871:Early Middle Ages

763:De revolutionibus

739:, Jean Pena, and

729:Robert Bellarmine

721:Francesco Patrizi

448:geocentric models

440:Arabic astronomer

418:Tashil al-Majisti

303:, the astronomer

52:celestial spheres

3474:

3429:Indian astronomy

3382:Sublunary sphere

3352:Hipparchic cycle

3291:Mural instrument

3266:Armillary sphere

3245:

3235:

3225:

3215:

3205:

2961:

2954:

2947:

2938:

2937:

2929:

2928:

2927:

2917:

2916:

2915:

2905:

2904:

2893:

2892:

2891:

2881:

2880:

2879:

2872:

2819:

2779:

2707:

2673:Neugebauer, Otto

2648:Open Court 1960.

2608:

2573:

2525:

2506:Koyré, Alexandre

2473:

2460:Gingerich, Owen

2457:

2311:

2276:, excerpts from

2272:Duhem, Pierre.

2265:Duhem, Pierre.

2255:

2185:

2178:

2172:

2165:

2159:

2154:

2148:

2133:

2127:

2120:

2114:

2107:

2101:

2094:

2088:

2085:

2079:

2078:pp. 345–48.

2072:

2066:

2063:

2057:

2050:

2044:

2037:

2031:

2024:

2018:

2011:

2005:

1990:

1984:

1977:

1971:

1964:

1958:

1951:

1945:

1938:

1932:

1931:

1875:

1866:

1865:

1845:

1835:

1829:

1822:

1816:

1809:

1803:

1796:

1790:

1783:

1777:

1776:

1775:

1773:

1754:

1748:

1741:

1735:

1728:

1722:

1715:

1709:

1702:

1696:

1689:

1683:

1676:

1670:

1663:

1657:

1650:

1644:

1637:

1631:

1624:

1618:

1617:

1609:

1603:

1601:

1573:

1567:

1566:

1558:

1552:

1545:

1536:

1529:

1523:

1516:

1510:

1496:

1490:

1478:

1472:

1465:

1459:

1452:

1446:

1445:26(1995): 33–61.

1436:

1430:

1423:

1414:

1388:

1382:

1373:

1367:

1358:

1352:

1341:

1335:

1328:

1322:

1315:

1309:

1298:

1292:

1285:

1279:

1272:

1266:

1259:

1253:

1246:

1240:

1233:

1227:

1224:

1215:

1212:

1206:

1201:F. M. Cornford,

1199:

1193:

1182:

1176:

1170:

1164:

1157:

1151:

1140:

1134:

1127:

1121:

1114:

1108:

1101:

1095:

1088:

1082:

1075:

1066:

1059:

1046:

1039:

1035:

1032:

1026:

1003:

1002:

995:

918:

859:Scipio Africanus

816:

759:Michael Maestlin

715:, 2nd ed., 1621)

556:Moses Maimonides

540:

539:

535:

532:

516:

515:

511:

508:

422:Thābit ibn Qurra

200:

196:

193:

84:apparent motions

28:Heavenly Spheres

21:Celestial sphere

3482:

3481:

3477:

3476:

3475:

3473:

3472:

3471:

3447:

3446:

3443:

3438:

3412:

3391:

3377:Spherical Earth

3312:Callippic cycle

3300:

3281:Equatorial ring

3249:

3243:

3233:

3223:

3213:

3203:

3188:

3179:Theon of Smyrna

2970:

2965:

2935:

2925:

2923:

2913:

2911:

2899:

2889:

2887:

2877:

2875:

2867:

2844:Wayback Machine

2827:

2822:

2816:

2731:Schofield, C.,

2724:Sambursky, S.,

2717:Rosen, Edward,

2704:

2612:Lloyd, G. E. R.

2605:

2570:

2522:

2492:Galileo Studies

2483:Jarrell, R.A.,

2476:Heath, Thomas,

2409:Grant, Edward,

2395:Grant, Edward,

2308:

2252:

2194:

2189:

2188:

2179:

2175:

2166:

2162:

2155:

2151:

2134:

2130:

2121:

2117:

2108:

2104:

2095:

2091:

2086:

2082:

2073:

2069:

2064:

2060:

2051:

2047:

2038:

2034:

2025:

2021:

2012:

2008:

1991:

1987:

1978:

1974:

1965:

1961:

1952:

1948:

1939:

1935:

1876:

1869:

1862:

1836:

1832:

1823:

1819:

1810:

1806:

1797:

1793:

1784:

1780:

1771:

1769:

1755:

1751:

1742:

1738:

1729:

1725:

1716:

1712:

1703:

1699:

1690:

1686:

1677:

1673:

1664:

1660:

1651:

1647:

1638:

1634:

1625:

1621:

1610:

1606:

1590:10.2307/2709773

1574:

1570:

1559:

1555:

1546:

1539:

1530:

1526:

1517:

1513:

1497:

1493:

1479:

1475:

1466:

1462:

1453:

1449:

1437:

1433:

1424:

1417:

1399:, p,1; Dreyer,

1389:

1385:

1381:, pp.63–64, 81.

1374:

1370:

1359:

1355:

1342:

1338:

1334:pp. 111–12, 148

1329:

1325:

1316:

1312:

1299:

1295:

1286:

1282:

1273:

1269:

1260:

1256:

1247:

1243:

1234:

1230:

1225:

1218:

1213:

1209:

1200:

1196:

1183:

1179:

1171:

1167:

1158:

1154:

1141:

1137:

1128:

1124:

1115:

1111:

1102:

1098:

1089:

1085:

1076:

1069:

1060:

1056:

1047:

1036:

1030:

1027:

1016:

1010:has an unclear

1004:

1000:

993:

988:

949:

880:Nicole Oresme,

863:Dream of Scipio

853:Dream of Scipio

818:

805:

800:

795:

774:Johannes Kepler

737:Michael Neander

657:

568:

560:Dante Alighieri

537:

533:

530:

528:

513:

509:

506:

504:

406:

397:De natura rerum

385:

233:planetary model

229:

198:

194:

171:Greek antiquity

167:

162:

156:

46:(Antwerp, 1539)

31:

24:

17:

12:

11:

5:

3480:

3470:

3469:

3464:

3459:

3440:

3439:

3437:

3436:

3431:

3426:

3420:

3418:

3414:

3413:

3411:

3410:

3405:

3399:

3397:

3393:

3392:

3390:

3389:

3384:

3379:

3374:

3369:

3364:

3359:

3354:

3349:

3344:

3339:

3334:

3329:

3324:

3319:

3314:

3308:

3306:

3302:

3301:

3299:

3298:

3293:

3288:

3283:

3278:

3273:

3268:

3263:

3257:

3255:

3251:

3250:

3248:

3247:

3241:On the Heavens

3237:

3227:

3217:

3214:(Eratosthenes)

3207:

3196:

3194:

3190:

3189:

3187:

3186:

3181:

3176:

3171:

3166:

3161:

3156:

3151:

3146:

3141:

3136:

3131:

3126:

3121:

3119:Philip of Opus

3116:

3111:

3106:

3101:

3096:

3091:

3086:

3081:

3076:

3071:

3066:

3061:

3056:

3051:

3046:

3041:

3036:

3031:

3026:

3021:

3016:

3011:

3006:

3001:

2996:

2991:

2986:

2980:

2978:

2972:

2971:

2964:

2963:

2956:

2949:

2941:

2934:

2933:

2921:

2909:

2897:

2885:

2865:

2864:

2858:

2846:

2833:

2826:

2825:External links

2823:

2821:

2820:

2814:

2801:

2794:

2787:

2780:

2764:

2763:Duckworth 2004

2757:

2750:

2736:

2729:

2722:

2721:Dover 1939/59.

2715:

2714:Routledge 1996

2710:Popper, Karl,

2708:

2702:

2687:

2670:

2656:

2649:

2642:

2627:

2609:

2603:

2588:

2574:

2568:

2553:

2541:Lewis, C. S.,

2539:

2526:

2520:

2502:

2488:

2481:

2474:

2465:

2458:

2421:

2407:

2393:

2375:

2368:

2351:

2334:

2319:

2312:

2306:

2288:

2270:

2263:

2256:

2250:

2235:

2224:

2217:

2210:

2203:

2195:

2193:

2190:

2187:

2186:

2173:

2160:

2149:

2128:

2115:

2102:

2089:

2080:

2067:

2058:

2045:

2032:

2019:

2006:

1994:Edo Hildericus

1985:

1972:

1959:

1946:

1933:

1904:10.1086/649338

1886:. 2nd Series.

1867:

1860:

1830:

1817:

1804:

1791:

1778:

1749:

1736:

1723:

1710:

1697:

1684:

1671:

1658:

1645:

1632:

1619:

1604:

1568:

1553:

1537:

1524:

1511:

1491:

1473:

1460:

1447:

1431:

1415:

1383:

1368:

1353:

1336:

1323:

1310:

1293:

1280:

1267:

1254:

1241:

1228:

1216:

1207:

1194:

1177:

1165:

1152:

1150:Routledge 1998

1135:

1122:

1109:

1096:

1083:

1067:

1053:

1052:

1049:

1048:

1012:citation style

1007:

1005:

998:

992:

989:

987:

986:

984:Sphere of fire

981:

976:

971:

966:

961:

956:

950:

948:

945:

927:King Charles V

796:

794:

791:

733:Giordano Bruno

656:

653:

567:

564:

547:Middle English

485:Kitāb al-Hayáh

469:Spanish Muslim

457:Book of Optics

405:

402:

384:

381:

228:

225:

180:sphere of fire

166:

163:

155:

152:

56:celestial orbs

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

3479:

3468:

3465:

3463:

3460:

3458:

3455:

3454:

3452:

3445:

3435:

3432:

3430:

3427:

3425:

3422:

3421:

3419:

3415:

3409:

3406:

3404:

3401:

3400:

3398:

3394:

3388:

3385:

3383:

3380:

3378:

3375:

3373:

3370:

3368:

3365:

3363:

3362:Metonic cycle

3360:

3358:

3355:

3353:

3350:

3348:

3347:Heliocentrism

3345:

3343:

3340:

3338:

3335:

3333:

3330:

3328:

3327:Counter-Earth

3325:

3323:

3320:

3318:

3315:

3313:

3310:

3309:

3307:

3303:

3297:

3294:

3292:

3289:

3287:

3284:

3282:

3279:

3277:

3274:

3272:

3269:

3267:

3264:

3262:

3259:

3258:

3256:

3252:

3246:

3242:

3238:

3236:

3234:(Aristarchus)

3232:

3228:

3226:

3222:

3218:

3216:

3212:

3208:

3206:

3202:

3198:

3197:

3195:

3191:

3185:

3182:

3180:

3177:

3175:

3172:

3170:

3167:

3165:

3162:

3160:

3157:

3155:

3152:

3150:

3147:

3145:

3142:

3140:

3137:

3135:

3132:

3130:

3127:

3125:

3122:

3120:

3117:

3115:

3112:

3110:

3107:

3105:

3102:

3100:

3097:

3095:

3092:

3090:

3087:

3085:

3082:

3080:

3077:

3075:

3072:

3070:

3067:

3065:

3062:

3060:

3057:

3055:

3052:

3050:

3047:

3045:

3042:

3040:

3037:

3035:

3032:

3030:

3027:

3025:

3022:

3020:

3017:

3015:

3012:

3010:

3007:

3005:

3002:

3000:

2997:

2995:

2992:

2990:

2987:

2985:

2982:

2981:

2979:

2977:

2973:

2969:

2962:

2957:

2955:

2950:

2948:

2943:

2942:

2939:

2932:

2922:

2920:

2910:

2908:

2903:

2898:

2896:

2886:

2884:

2874:

2873:

2870:

2862:

2859:

2857:

2856:

2851:

2847:

2845:

2841:

2838:

2835:Dennis Duke,

2834:

2832:

2829:

2828:

2817:

2811:

2807:

2802:

2799:

2795:

2792:

2788:

2785:

2781:

2777:

2773:

2769:

2765:

2762:

2758:

2755:

2751:

2749:

2748:0-7156-2205-6

2745:

2741:

2737:

2734:

2730:

2727:

2723:

2720:

2716:

2713:

2709:

2705:

2699:

2695:

2694:

2688:

2686:

2685:0-387-06995-X

2682:

2678:

2674:

2671:

2669:

2668:0-521-77852-2

2665:

2661:

2657:

2654:

2650:

2647:

2644:Mach, Ernst,

2643:

2640:

2639:0-521-55619-8

2636:

2632:

2628:

2625:

2624:0-521-09456-9

2621:

2617:

2613:

2610:

2606:

2600:

2596:

2595:

2589:

2587:

2586:0-226-48233-2

2583:

2579:

2575:

2571:

2565:

2561:

2560:

2554:

2552:

2551:0-521-09450-X

2548:

2544:

2540:

2537:

2533:

2532:

2527:

2523:

2517:

2513:

2512:

2507:

2503:

2501:

2500:0-85527-354-2

2497:

2493:

2489:

2486:

2482:

2479:

2475:

2471:

2466:

2463:

2459:

2455:

2451:

2447:

2443:

2439:

2435:

2431:

2427:

2422:

2420:

2419:0-521-56762-9

2416:

2412:

2408:

2406:

2405:0-521-56509-X

2402:

2398:

2394:

2392:

2391:0-226-74951-7

2388:

2384:

2380:

2376:

2373:

2369:

2367:

2366:0-226-24823-2

2363:

2359:

2355:

2352:

2350:

2349:0-87169-943-5

2346:

2342:

2339:

2335:

2332:

2328:

2324:

2320:

2317:

2313:

2309:

2303:

2299:

2298:

2293:

2289:

2287:

2286:0-226-16923-5

2283:

2279:

2275:

2271:

2268:

2264:

2261:

2257:

2253:

2247:

2243:

2242:

2236:

2233:

2229:

2225:

2222:

2218:

2215:

2211:

2208:

2204:

2201:

2197:

2196:

2183:

2177:

2170:

2164:

2158:

2153:

2146:

2145:0-521-09450-X

2142:

2138:

2135:C. S. Lewis,

2132:

2125:

2119:

2112:

2106:

2099:

2093:

2084:

2077:

2071:

2062:

2055:

2049:

2042:

2036:

2029:

2023:

2016:

2010:

2003:

1999:

1995:

1989:

1982:

1976:

1969:

1963:

1956:

1950:

1943:

1937:

1929:

1925:

1921:

1917:

1913:

1909:

1905:

1901:

1897:

1893:

1889:

1885:

1881:

1874:

1872:

1863:

1857:

1853:

1849:

1844:

1843:

1834:

1827:

1821:

1814:

1808:

1802:, pp. 249–50.

1801:

1795:

1788:

1782:

1768:

1764:

1760:

1753:

1746:

1740:

1733:

1727:

1720:

1714:

1707:

1701:

1694:

1688:

1681:

1675:

1668:

1662:

1656:, pp. 433–43.

1655:

1649:

1642:

1636:

1629:

1623:

1615:

1608:

1599:

1595:

1591:

1587:

1584:(1): 13–31 .

1583:

1579:

1572:

1564:

1557:

1550:

1544:

1542:

1534:

1528:

1521:

1515:

1509:

1508:0-300-01387-6

1505:

1501:

1495:

1488:

1483:

1477:

1470:

1464:

1457:

1451:

1444:

1441:

1435:

1428:

1422:

1420:

1412:

1408:

1404:

1403:

1398:

1397:

1392:

1387:

1380:

1379:

1372:

1365:

1364:

1357:

1351:

1348:

1347:

1340:

1333:

1327:

1320:

1314:

1307:

1303:

1297:

1290:

1284:

1277:

1271:

1264:

1258:

1251:

1245:

1238:

1232:

1223:

1221:

1211:

1204:

1198:

1191:

1187:

1181:

1175:

1169:

1162:

1156:

1149:

1145:

1139:

1133:, pp. 37, 40.

1132:

1126:

1119:

1113:

1106:

1100:

1093:

1087:

1080:

1074:

1072:

1064:

1058:

1054:

1045:

1042:

1034:

1024:

1020:

1014:

1013:

1008:This article

1006:

997:

996:

985:

982:

980:

979:Seven heavens

977:

975:

974:Primum Mobile

972:

970:

967:

965:

962:

960:

959:Body of light

957:

955:

952:

951:

944:

941:

940:

934:

932:

928:

924:

923:

917:

912:

911:Nicole Oresme

908:

904:

903:

902:Divine Comedy

898:

897:

892:

883:

878:

874:

872:

868:

864:

860:

856:

854:

849:

841:

839:

838:Divine Comedy

834:

830:

826:

822:

817:

814:

813:

808:

802:

790:

788:

784:

780:

775:

771:

768:In his early

766:

764:

760:

756:

752:

750:

746:

742:

738:

734:

730:

726:

722:

714:

709:

705:

703:

699:

695:

694:Thomas Digges

690:

688:

684:

680:

676:

675:

670:

661:

652:

650:

646:

645:unmoved mover

642:

638:

634:

628:

626:

622:

618:

614:

609:

607:

603:

601:

597:

593:

589:

585:

580:

577:

572:

563:

561:

557:

553:

552:

548:

544:

526:

522:

521:

502:

498:

493:

488:

486:

482:

477:

474:

470:

465:

463:

459:

458:

453:

449:

445:

442:and polymath

441:

436:

433:

429:

428:

423:

419:

415:

411:

398:

394:

389:

380:

378:

374:

370:

366:

362:

358:

354:

350:

346:

342:

338:

333:

332:Earth radii.

330:

326:

322:

318:

314:

310:

306:

302:

301:

292:

288:

284:

280:

276:

271:

267:

265:

261:

256:

252:

251:

245:

242:

238:

234:

224:

221:

220:

215:

211:

207:

202:

189:

184:

181:

176:

172:

161:

151:

149:

145:

141:

137:

133:

128:

125:

119:

117:

113:

109:

104:

99:

97:

93:

89:

85:

81:

77:

73:

69:

65:

61:

57:

53:

45:

42:

41:Peter Apian's

37:

33:

29:

22:

3444:

3316:

3240:

3230:

3224:(Hipparchus)

3220:

3211:Catasterismi

3210:

3200:

3059:Eratosthenes

2931:Solar System

2854:

2805:

2797:

2790:

2783:

2771:

2760:

2753:

2739:

2732:

2725:

2718:

2711:

2692:

2676:

2659:

2652:

2645:

2630:

2615:

2593:

2577:

2558:

2542:

2535:

2529:

2510:

2491:

2484:

2477:

2469:

2461:

2432:(1): 57–73.

2429:

2425:

2410:

2396:

2382:

2378:

2371:

2357:

2354:Field, J. V.

2340:

2337:

2322:

2315:

2296:

2277:

2273:

2266:

2240:

2231:

2227:

2220:

2213:

2206:

2199:

2192:Bibliography

2181:

2176:

2168:

2163:

2152:

2136:

2131:

2123:

2118:

2110:

2105:

2097:

2092:

2083:

2075:

2070:

2061:

2053:

2048:

2040:

2035:

2027:

2022:

2014:

2009:

2001:

1997:

1988:

1980:

1975:

1967:

1962:

1954:

1949:

1941:

1936:

1887:

1883:

1841:

1833:

1825:

1820:

1812:

1807:

1799:

1794:

1786:

1781:

1770:, retrieved

1766:

1762:

1752:

1744:

1743:Van Helden,

1739:

1731:

1730:Van Helden,

1726:

1718:

1713:

1705:

1704:Van Helden,

1700:

1692:

1691:Van Helden,

1687:

1679:

1678:Van Helden,

1674:

1669:, pp. 434–8.

1666:

1661:

1653:

1648:

1640:

1635:

1627:

1622:

1613:

1607:

1581:

1577:

1571:

1562:

1556:

1548:

1547:Van Helden,

1532:

1531:Van Helden,

1527:

1522:, pp. 29–31.

1519:

1518:Van Helden,

1514:

1499:

1494:

1486:

1481:

1476:

1468:

1463:

1455:

1450:

1442:

1434:

1426:

1425:Neugebauer,

1400:

1394:

1386:

1376:

1371:

1361:

1356:

1344:

1339:

1331:

1330:Neugebauer,

1326:

1318:

1313:

1305:

1301:

1296:

1288:

1283:

1275:

1270:

1262:

1257:

1249:

1244:

1236:

1235:Neugebauer,

1231:

1210:

1202:

1197:

1189:

1185:

1180:

1173:

1168:

1160:

1155:

1147:

1143:

1138:

1130:

1129:Van Helden,

1125:

1117:

1116:Van Helden,

1112:

1107:, pp. 437–8.

1104:

1099:

1094:, pp. 28–40.

1091:

1090:Van Helden,

1086:

1078:

1062:

1057:

1037:

1028:

1009:

937:

935:

921:

900:

894:

887:

881:

862:

851:

845:

836:

833:Gustave Doré

810:

804:

798:

769:

767:

762:

753:

718:

712:

697:

691:

678:

672:

666:

629:

619:doctrine of

610:

606:Edward Grant

604:

581:

573:

569:

549:

542:

518:

500:

492:universities

489:

484:

478:

466:

455:

451:

437:

425:

417:

413:

407:

396:

334:

320:

312:

298:

296:

290:

277:, eccentric

248:

246:

230:

217:

203:

199: 528/4

185:

168:

129:

120:

100:

96:quintessence

60:cosmological

55:

51:

49:

44:Cosmographia

43:

32:

3342:Geocentrism

3254:Instruments

3244:(Aristotle)

3049:Cleostratus

3014:Aristarchus

2994:Anaximander

2976:Astronomers

2919:Outer space

2798:Tycho Brahe

2200:Metaphysics

2182:The Lusiads

2122:Macrobius,

1970:pp. 526–45.

1828:pp. 328–30.

1747:, pp. 37–9.

1721:, pp. 97–8.

1682:, pp. 33–4.

1626:Goldstein,

1551:, pp. 31–2.

1319:Metaphysics

1302:Metaphysics

1300:Aristotle,

939:The Lusiads

807:C. S. Lewis

755:Tycho Brahe

725:Peter Ramus

655:Renaissance

649:Prime Mover

529:410,818,517

525:Roger Bacon

471:astronomer

410:al-Farghānī

383:Middle Ages

250:Metaphysics

175:Anaximander

88:fixed stars

3451:Categories

3417:Influenced

3396:Influences

3367:Octaeteris

3296:Triquetrum

3184:Timocharis

3169:Theodosius

3129:Posidonius

3089:Hipparchus

3079:Heraclides

3019:Aristyllus

3004:Apollonius

2999:Andronicus

2198:Aristotle

1850:. p.

1811:Lindberg,

1798:Lindberg,

1789:pp. 382–3.

1643:pp. 563–6.

1628:Al-Bitrūjī

1485:(See p521

1391:Taliaferro

1343:Pedersen,

1205:, pp. 54–7

1077:Lindberg,

1023:footnoting

857:the elder

840:, Paradiso

637:revelation

625:al-Jurjani

613:mutakallim

543:Opus Majus

520:Opus Majus

505:73,387,747

432:Al-Battānī

377:al-Bitruji

214:Parmenides

210:Xenophanes

206:Pythagoras

197: – c.

195: 585

188:Anaximenes

80:Copernicus

3271:Astrolabe

3204:(Ptolemy)

3124:Philolaus

3114:Oenopides

3099:Hypsicles

3044:Cleomedes

3039:Callippus

3029:Autolycus

2984:Aglaonice

2895:Astronomy

2853:Ptolemy,

2454:117056401

2294:(2007) .

2214:Principia

1928:142586786

1912:0369-7827

1815:, p. 250.

1265:, p. 150.

1263:Aristotle

1081:, p. 251.

1065:, p. 440.

893:, in the

867:Macrobius

592:firmament

317:epicycles

255:Aristotle

241:Callippus

116:expanding

108:epicycles

72:Aristotle

3372:Solstice

3305:Concepts

3201:Almagest

3144:Seleucus

3104:Menelaus

3064:Euctemon

2855:Almagest

2840:Archived

2770:(1946).

2508:(1957).

2223:CUP 2002

1734:, p. 38.

1708:, p. 35.

1695:, p. 36.

1535:, p. 31.

1375:Linton,

1248:Dreyer,

1031:May 2023

1019:citation

947:See also

922:De caelo

907:Empyrean

896:Paradiso

829:Beatrice

815:, p. 99.

749:parallax

683:universe

584:empyrean

481:al-'Urḍi

464:matter.

414:Almagest

329:epicycle

325:deferent

300:Almagest

279:deferent

275:epicycle

3276:Dioptra

3139:Pytheas

3134:Ptolemy

3084:Hicetas

3074:Geminus

3069:Eudoxus

3024:Attalus

2989:Agrippa

2883:History

2869:Portals

2434:Bibcode

2096:Field,

2074:Grant,

2013:Koyre,

1966:Grant,

1957:p. 527.

1953:Grant,

1944:p. 541.

1940:Grant,

1892:Bibcode

1824:Grant,

1785:Grant,

1772:2 March

1717:Lewis,

1665:Grant,

1652:Grant,

1639:Grant,

1630:, p. 6.

1598:2709773

1480:In his

1360:Crowe,

1321:1072b4.

1261:Lloyd,

1159:Heath

1120:, p. 3.

1103:Grant,

1061:Grant,

899:of his

621:atomism

617:Ash'ari

596:Genesis

536:⁄

512:⁄

357:Jupiter

341:Mercury

311:in his

305:Ptolemy

297:In his

293:, 1474.

285:point.

247:In his

219:Timaeus

154:History

92:planets

86:of the

76:Ptolemy

68:Eudoxus

3387:Zodiac

3337:Equant

3286:Gnomon

3164:Thales

3159:Strabo

3009:Aratus

2812:

2746:

2700:

2683:

2666:

2637:

2622:

2601:

2584:

2566:

2549:

2518:

2498:

2452:

2417:

2403:

2389:

2364:

2347:

2329:

2304:

2284:

2248:

2143:

1926:

1920:301979

1918:

1910:

1884:Osiris

1858:

1596:

1506:

1407:pp.160

1163:pp26–8

931:Psalms

848:Cicero

647:, the

639:. The

633:angels

600:angels

416:, the

361:Saturn

359:, and

309:cosmos

283:equant

260:aether

235:using

136:Kepler

3193:Works

3109:Meton

3054:Conon

2907:Stars

2774:. In

2450:S2CID

2379:Isis,

2262:>.

2230:, in

1924:S2CID

1916:JSTOR

1594:JSTOR

1350:p. 87

991:Notes

891:Dante

825:Dante

783:radii

745:comet

687:stars

462:solid

345:Venus

64:Plato

54:, or

3034:Bion

2810:ISBN

2744:ISBN

2698:ISBN

2681:ISBN

2664:ISBN

2635:ISBN

2620:ISBN

2599:ISBN

2582:ISBN

2564:ISBN

2547:ISBN

2516:ISBN

2496:ISBN

2415:ISBN

2401:ISBN

2387:ISBN

2362:ISBN

2345:ISBN

2327:ISBN

2302:ISBN

2282:ISBN

2246:ISBN

2141:ISBN

1908:ISSN

1856:ISBN

1774:2010