40:

540:

absurd), it cannot, however regarded, possess as much reality as God, and hence cannot demand as much reality in its cause as God possesses. So the argument seems to fall short of positing God as cause of the idea." He goes on to say that

Descartes must, therefore be relying on something more than the general principle that there must be as much formal reality in the cause of an idea as there is objective reality in the idea itself. Instead, he suggests, Descartes is relying on special features of the idea of God: "the infinity and perfection of God, represented in his idea, are of such a special character, so far in excess of any other possible cause, that the only thing adequate to produce an idea of that would be the thing itself, God."

552:"an unsatisfactory line of defence". He refers to Descartes own analogy of a man who had an idea of a very complex machine from which it could be inferred that he had either seen the machine, been told about the machine or was clever enough to invent it. He adds, "But clearly such inferences will hold only if the man has a quite determinate idea of the machine. If a man comes up and says that he has an idea of a marvellous machine which will feed the hungry by making proteins out of sand, I shall be impressed neither by his experience nor by his powers of invention if it turns out that that is all there is to the idea, and he has no conception, or only the haziest conception, of how such a machine might work."

410:'Formal reality' is roughly what we mean by 'actually existing.' 'Objective reality' does not mean objective as opposed to subjective but is more like the object of one's thoughts irrespective of whether or not it actually exists. Cottingham says that 'objective reality' is the 'representational content of an idea'. Hatfield says "think of an "object" of desire – a championship for your favorite sports team, say. It may not now exist, and it need never have existed. In Descartes' terminology, what has "objective reality" is something contained in the subject's mental state and so may even be called "subjective" in present-day terms."

348:

objective reality than the ideas that represent finite substances. Now it is manifest by the natural light that there must be at least as much reality in the efficient and total cause as in the effect of that cause. For where, I ask, could the effect get its reality from, if not from the cause? And how could the cause give it to the effect unless it possessed it? It follows from this both that something cannot arise from nothing, and also that what is more perfect—that is, contains in itself more reality—cannot arise from what is less perfect.

496:

continue to infinity but firstly, this gradual increase in knowledge is itself a sign of imperfection and, secondly, God I take to be actually infinite, so that nothing can be added to his perfection whereas increasing knowledge will never reach the point where it is not capable of a further increase. Finally, the objective being of an idea cannot be produced merely by potential being, which strictly speaking is nothing, but only by actual or formal being.

527:

of formal reality that the thing being thought about would have if it existed. Descartes offers no reason why this should be so. Wilson says, "Descartes has simply made an arbitrary stipulation here." There seems to be no good reason why we could not maintain different degrees of objective reality but insist that the idea of an infinite substance still has less reality than the amount of reality conferred by the formal reality of a finite substance.

1961:

327:

argument, he has not established that the world exists. Instead, he starts with the fact that he has an idea of God and concludes "that the mere fact that I exist and have within me an idea of a most perfect being, that is, God, provides a very clear proof that God indeed exists." He says, "it is no surprise that God, in creating me, should have placed this idea in me to be, as it were, the mark of the craftsman stamped on his work."

363:"I have … made it quite clear how reality admits of more and less. A substance is more of a thing than a mode; if there are real qualities or incomplete substances, they are things to a greater extent than modes, but to a lesser extent than complete substances; and, finally, if there is an infinite and independent substance, it is more of a thing than a finite and dependent substance. All this is completely self-evident."

574:

561:

which may be eclipsing his natural light, and to accustom himself to believing in the primary notions, which are as evident and true as anything can be, in preference to opinions which are obscure and false, albeit fixed in the mind by long habit… I cannot force this truth on my readers if they are lazy, since it depends solely on their exercising their own powers of thought.

523:

of a flower but this needs to be unpacked. 'Reality' cannot be equated with 'existence' for, apart from the fact that 'degrees of existence' is hardly less problematic than 'degrees of reality', as Wilson comments, "reality must not be confused with existence: otherwise the existence of God would be overtly assumed in the premises of the argument."

452:

If ideas are considered simply as modes of thought, they are all equal and appear to come from within me; in so far as different ideas represent different things they differ widely. Ideas which represent substances contain within themselves more objective reality than the ideas which merely represent

439:

Since the idea of God contains the level of (objective) reality appropriate to an infinite substance it is legitimate to ask where an idea with this level of reality came from. After considering various options

Descartes concludes that it must come from a substance that has at least the same level of

352:

Descartes goes on to describe this as 'transparently true'. Commenting on this passage

Williams says, "This is a piece of scholastic metaphysics, and it is one of the most striking indications of the historical gap that exists between Descartes' thought and our own, despite the modern reality of much

522:

Hobbes' complaint that

Descartes has not offered an adequate account of degrees of reality does not seem to have been answered and Descartes' response that it is 'self-evident' surely is not enough. There may be some superficial appeal in the claim that an actual flower has more reality than an idea

426:

reality than the idea of a finite substance. Kenny notes, "we sometimes use the word 'reality' to distinguish fact from fiction: on this view, the idea of a lion would have more objective reality than the idea of a unicorn since lions exist and unicorns do not. But this is not what

Descartes means."

380:

A substance is something that exists independently. The only thing that truly exists independently is an infinite substance for it does not rely on anything else for its existence. In this context 'infinite substance' means 'God'. A finite substance can exist independently other than its reliance on

356:

In his own time, it was challenged by Hobbes who in the

Objections says, "Moreover, M. Descartes should consider afresh what 'more reality' means. Does reality admit of more and less? Or does he think one thing can be more of a thing than another? If so, he should consider how this can be explained

526:

Even if the argument is judged on its own terms and we grant that there can be degrees of formal reality and degrees of objective reality there are still significant problems. Crucial to the argument as it is normally reconstructed is that the degree of objective reality is determined by the degree

405:

The nature of an idea is such that of itself it requires no formal reality except what it derives from my thought, of which it is a mode. But in order for a given idea to contain such and such objective reality, it must surely derive it from some cause which contains at least as much formal reality

388:

The degree of reality is related to the way in which something is dependent—"Modes are logically dependent on substance; they 'inhere in it as subject.'... Created substances are not logically, but causally, dependent on God. They do not inhere in God as subject, but are effects of God as creator."

560:

I do not see what I can add to make it any clearer that the idea in question could not be present to my mind unless a supreme being existed. I can only say that it depends on the reader: if he attends carefully to what I have written he should be able to free himself from the preconceived opinions

551:

infinite, can in no way be grasped. But it can still be understood, in so far as we can clearly and distinctly understand that something is such that no limitations can be found in it, and this amounts to understanding clearly that it is infinite." Cottingham argues that making this distinction is

504:

I couldn't exist as the kind of thing that has this idea of God if God didn't exist, for I didn't create myself, I haven't always existed, and, although there may be a series of causes that led to my existence, the ultimate cause must be such that it could give me the idea of God and this, for the

470:

If the objective reality of any of my ideas turns out to be so great that I am sure the same reality does not reside in me, either formally or eminently (i.e. potentially), and hence that I myself cannot be its cause, it will necessarily follow that I am not alone in the world, but that some other

435:

Using the above ideas

Descartes can claim that it is obvious that there must be at least as much reality in the cause as in the effect for if there was not you would be getting something from nothing. He says "the idea of heat, or of a stone, cannot exist in me unless it is put there by some cause

518:

Cunning notes that "Commentators have argued that there is not much hope for the argument from objective reality." Wilson says that she will say little about

Descartes arguments for the existence of God for "while these arguments are interesting enough, I don’t think Descartes is in a position to

495:

The perfections which I attribute to God do not exist in me potentially. It is true that I have many potentialities which are not yet actual but this irrelevant to the idea of God, which contains absolutely nothing that is potential. It might be thought that my gradual increase in knowledge could

463:

Although the reality in my ideas is merely objective reality what ultimately causes those ideas must contain the same formal reality. Although one idea may originate from another, there cannot be an infinite regress here; eventually one must reach a primary idea, the cause of which will contain

539:

it may be necessary for the objective reality to be less than the formal reality of the thing represented. Williams points out, "God, as the argument insists, has more reality or perfection than anything else whatever. Hence if

Descartes' idea of God is not itself God (which would of course be

347:

Undoubtedly, the ideas which represent substances to me amount to something more and, so to speak, contain within themselves more objective reality than the ideas which merely represent modes or accidents. Again, the idea that gives me my understanding of a supreme God…certainly has in it more

326:

which attempts to deduce the existence of God from the nature of God; in

Meditation III he presents an argument for the existence of God from one of the effects of God's activity. Descartes cannot start with the existence of the world or with some feature of the world for, at this stage of his

555:

Finally, it might be added, for this proof to do the work Descartes is asking of it the proof needs to be clear and distinct. Given the above considerations this is unconvincing. In the second set of replies Descartes says this is the fault of the reader:

413:

Crucial to Descartes argument is the way in which the levels of objective reality are determined. The level of objective reality is determined by the formal reality of what is being represented or thought about. So every idea I have has the lowest level of

478:

By the word 'God' I understand a substance that is infinite, eternal, immutable, etc. These attributes are such that it doesn't seem possible for them to have originated from me alone. So from what has been said it must be concluded that God necessarily

534:

he says of objective existence, "this mode of being is of course much less perfect than that possessed by things which exist outside the intellect; but, as I did explain, it is not therefore simply nothing." Despite what Descartes appears to say in the

459:

It follows from this both that something cannot arise from nothing, and also that what contains more reality cannot arise from what contains less reality. And this applies not only when considering formal reality, but also when considering objective

436:

which contains at least as much reality as I conceive to be in the heat or in the stone. For although this cause does not transfer any of its actual or formal reality to my idea, it should not on that account be supposed that it must be less real."

519:

defend their soundness very forcefully." Williams comments that "Descartes took these hopeless arguments for the existence of God to be self-evidently valid, conditioned in this by historical and perhaps also by temperamental factors."

474:

In addition to being aware of myself, I have other ideas— of God, corporeal and inanimate things, angels, animals and other men like myself. Except for the idea of God, it doesn't seem impossible that these ideas originated from within

487:

Although I have the idea of substance in me by virtue of being a substance, this does not account for my having the idea of an infinite substance, when I am finite. This idea must have come from some substance which really was

392:

To avoid confusion, it is important to note that the degree of reality is not related to size—a bowling ball does not have more reality than a table tennis ball; a forest fire does not have more reality than a candle flame.

508:

This idea of God didn't come to me via the senses, nor did I invent this idea for I am plainly unable either to take away anything from it or to add anything to it. The only remaining alternative is that it is innate in

384:

A 'mode' is "a way or manner in which something occurs or is experienced, expressed, or done." In this scheme, a substance (e.g. a mind) will have an attribute (thought) and the mode might be willing or having an idea.

491:

I cannot have gained the idea of the infinite merely by negating the finite. On the contrary, to know that I am finite means knowing that I lack something and so must first have the idea of the infinite to make that

543:

Then there is the problem of how it can be possible for a finite mind to have a clear and distinct idea of an infinite God. Descartes was challenged on this and in the first set of

427:

In this instance the idea of a lion and the idea of a unicorn would have the same objective reality because a lion and a unicorn (if it existed) would both be finite substances.

467:

Ideas are like pictures which can easily fall short of the perfection of the things from which they are taken, but which cannot contain anything greater or more perfect.

453:

modes; the idea that gives me my understanding of a supreme God, (eternal, infinite, etc.) has more objective reality than the ideas that represent finite substances.

39:

366:

To understand Descartes' Trademark Argument it is not necessary to fully understand the underlying Aristotelian metaphysics but it is necessary to know that

607:

659:

This has come to be known as the trademark argument as it claims that each person's idea of God is the trademark, hallmark or stamp of their divine creator

381:

an infinite substance. 'Substance' does not imply 'physical substance' — for Descartes the body is one substance but the mind is also a substance.

353:

else that he writes, that he can unblinkingly accept this unintuitive and barely comprehensible principle as self-evident in the light of reason."

1935:

456:

It is manifest by the natural light that there must be at least as much reality in the efficient and total cause as in the effect of that cause.

313:. The name derives from the fact that the idea of God existing in each person "is the trademark, hallmark or stamp of their divine creator".

1983:

449:

My ideas may be innate, adventitious (i.e. come from outside me), or have been invented by me. As yet I don't know their true origin.

335:

To understand Descartes' argument it is necessary to understand some of the metaphysical assumptions that Descartes is using.

868:

183:

1368:

1343:

1663:

612:

279:

178:

1619:

966:

1531:

913:

843:

813:

759:

725:

691:

652:

357:

to us with that degree of clarity that every demonstration calls for, and which he himself has employed elsewhere."

1859:

1589:

317:

203:

1183:

1927:

1724:

1719:

1458:

1658:

1842:

131:

116:

322:

Descartes provides two arguments for the existence of God. In Meditation V he presents a version of the

1907:

1178:

231:

1988:

23:

1809:

298:

246:

101:

1940:

1889:

1734:

1373:

208:

1874:

1819:

1678:

1575:

1094:

272:

193:

1624:

959:

634:

69:

1764:

1668:

1438:

1401:

1353:

1241:

644:

638:

188:

106:

1784:

1433:

323:

213:

8:

1879:

1510:

1448:

1358:

1295:

1205:

1193:

236:

126:

1864:

1827:

1794:

1789:

1754:

1711:

1599:

1570:

1490:

1453:

988:

265:

251:

1960:

1917:

1550:

1495:

1485:

1477:

1443:

1328:

1277:

1099:

952:

909:

864:

839:

809:

802:

755:

721:

687:

648:

579:

198:

141:

111:

775:

310:

31:

1769:

1629:

1581:

1500:

1318:

587:

306:

152:

121:

85:

420:

reality, for every idea is a mode, but the idea of an infinite substance has more

1964:

1869:

1799:

1555:

1505:

1323:

1210:

136:

74:

64:

1729:

1396:

1220:

1215:

1188:

1057:

241:

79:

1977:

1639:

1540:

1132:

1037:

1854:

1759:

1749:

1649:

1614:

1594:

1535:

1463:

1348:

1251:

1198:

146:

54:

440:(formal) reality. Therefore, an infinite substance, i.e. God, must exist.

1832:

1744:

1673:

1609:

1565:

1383:

1338:

1291:

1225:

1069:

1032:

159:

59:

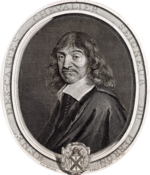

640:

The God Confusion – Why Nobody Knows the Answer to the Ultimate Question

1897:

1804:

1779:

1739:

1333:

1104:

1089:

1084:

1052:

1027:

464:

formally all the reality which is present only objectively in the idea.

91:

1560:

1391:

1282:

1079:

1064:

1047:

1042:

1022:

1912:

1545:

1127:

1074:

975:

302:

1902:

1604:

1515:

1363:

1310:

1246:

1140:

370:

an infinite substance has the most reality and more reality than

1850:

1413:

1000:

1406:

1256:

1147:

1122:

1017:

904:

Cottingham, John; Stoothoff, Robert; Murdoch, Dugald (1985).

716:

Cottingham, John; Stoothoff, Robert; Murdoch, Dugald (1984).

1634:

1417:

1287:

944:

903:

715:

684:

Descartes: The Project of Pure Enquiry (Routledge Classics

1774:

1261:

1161:

430:

711:

709:

707:

705:

703:

530:

Descartes may be inconsistent on this point for in the

513:

396:

373:

a finite substance, which in turn has more reality than

897:

309:

developed by the French philosopher and mathematician

700:

569:

801:

471:thing which is the cause of this idea also exists.

861:Argument and Persuasion in Descartes' Meditations

829:

827:

825:

443:

1975:

745:

743:

741:

739:

737:

677:

675:

673:

671:

669:

667:

884:

882:

880:

822:

500:Additional argument for the existence of God:

960:

273:

906:The philosophical writings of Descartes vol1

795:

793:

734:

718:The philosophical writings of Descartes vol2

664:

934:Meditations and Other Metaphysical Writings

877:

852:

1426:

967:

953:

833:

406:as there is objective reality in the idea.

280:

266:

908:. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

790:

720:. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

330:

1710:

893:. Bombay: Popular Prakashan Private Ltd.

749:

681:

633:

858:

1976:

987:

888:

431:Applying the causal adequacy principle

1699:

986:

948:

799:

338:

514:Criticisms of the trademark argument

397:Formal reality and Objective reality

863:. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

804:Descartes A Study of his Philosophy

613:The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy

505:reasons already given, will be God.

179:Rules for the Direction of the Mind

13:

1984:Arguments for the existence of God

14:

2000:

1532:Attributes of God in Christianity

16:Argument for the existence of God

1959:

572:

38:

1590:Great Architect of the Universe

778:. Oxford University Press. 2017

204:Meditations on First Philosophy

768:

627:

600:

444:Outline of Descartes' argument

1:

1369:Trinity of the Church Fathers

938:Christopher Hamilton (2003),

752:Descartes and the Meditations

593:

1700:

974:

776:"Oxford Living Dictionaries"

7:

1620:Phenomenological definition

565:

360:To this Descartes replies:

10:

2005:

926:

808:. New York: Random House.

682:Williams, Bernard (1996).

232:Christina, Queen of Sweden

1957:

1926:

1888:

1841:

1818:

1706:

1695:

1648:

1524:

1476:

1382:

1309:

1270:

1234:

1171:

1160:

1113:

1008:

999:

995:

982:

889:Wilson, Margaret (1960).

834:Cottingham, John (1986).

247:Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

102:Causal adequacy principle

1374:Trinitarian universalism

940:Understanding Philosophy

686:. Cambridge: Routledge.

483:Further considerations:

209:Principles of Philosophy

1576:Godhead in Christianity

859:Cunning, David (2010).

800:Kenny, Anthony (1968).

750:Hatfield, Gary (2003).

194:Discourse on the Method

563:

408:

350:

331:Underlying assumptions

1402:Fate of the unlearned

1354:Shield of the Trinity

838:. Oxford: Blackwell.

754:. London: Routledge.

645:Bloomsbury Publishing

558:

547:says, "the infinite,

403:

345:

608:"trademark argument"

324:ontological argument

214:Passions of the Soul

184:The Search for Truth

1936:Slavic Native Faith

1359:Trinitarian formula

1296:Father of Greatness

1179:Abrahamic religions

237:Nicolas Malebranche

107:Mind–body dichotomy

75:Doubt and certainty

1898:Abrahamic prophecy

1828:Ayyavazhi theology

1600:Apophatic theology

989:Conceptions of God

339:Degrees of reality

294:trademark argument

252:Francine Descartes

97:Trademark argument

1971:

1970:

1953:

1952:

1949:

1948:

1691:

1690:

1687:

1686:

1582:Latter Day Saints

1551:Divine simplicity

1472:

1471:

1329:Consubstantiality

1305:

1304:

1156:

1155:

1100:Theistic finitism

870:978-0-19-539960-8

580:Philosophy portal

290:

289:

142:Balloonist theory

117:Coordinate system

112:Analytic geometry

1996:

1963:

1708:

1707:

1697:

1696:

1584:

1424:

1423:

1319:Athanasian Creed

1169:

1168:

1006:

1005:

997:

996:

984:

983:

969:

962:

955:

946:

945:

932:René Descartes,

920:

919:

901:

895:

894:

886:

875:

874:

856:

850:

849:

831:

820:

819:

807:

797:

788:

787:

785:

783:

772:

766:

765:

747:

732:

731:

713:

698:

697:

679:

662:

661:

631:

625:

624:

622:

620:

604:

588:Cartesian Circle

582:

577:

576:

575:

401:Descartes says,

343:Descartes says,

307:existence of God

282:

275:

268:

122:Cartesian circle

86:Cogito, ergo sum

42:

19:

18:

2004:

2003:

1999:

1998:

1997:

1995:

1994:

1993:

1974:

1973:

1972:

1967:

1965:Religion portal

1945:

1922:

1884:

1865:Holy Scriptures

1837:

1814:

1702:

1683:

1644:

1580:

1556:Divine presence

1520:

1468:

1422:

1378:

1324:Comma Johanneum

1301:

1266:

1230:

1164:

1152:

1109:

991:

978:

973:

929:

924:

923:

916:

902:

898:

887:

878:

871:

857:

853:

846:

832:

823:

816:

798:

791:

781:

779:

774:

773:

769:

762:

748:

735:

728:

714:

701:

694:

680:

665:

655:

632:

628:

618:

616:

606:

605:

601:

596:

578:

573:

571:

568:

516:

446:

433:

399:

341:

333:

286:

257:

256:

227:

219:

218:

174:

166:

165:

137:Cartesian diver

65:Foundationalism

50:

17:

12:

11:

5:

2002:

1992:

1991:

1989:René Descartes

1986:

1969:

1968:

1958:

1955:

1954:

1951:

1950:

1947:

1946:

1944:

1943:

1938:

1932:

1930:

1924:

1923:

1921:

1920:

1915:

1910:

1905:

1900:

1894:

1892:

1886:

1885:

1883:

1882:

1877:

1875:Predestination

1872:

1867:

1862:

1857:

1847:

1845:

1839:

1838:

1836:

1835:

1830:

1824:

1822:

1816:

1815:

1813:

1812:

1807:

1802:

1797:

1792:

1787:

1782:

1777:

1772:

1767:

1762:

1757:

1752:

1747:

1742:

1737:

1732:

1730:Biblical canon

1727:

1722:

1716:

1714:

1704:

1703:

1693:

1692:

1689:

1688:

1685:

1684:

1682:

1681:

1676:

1671:

1666:

1661:

1655:

1653:

1646:

1645:

1643:

1642:

1637:

1632:

1627:

1622:

1617:

1612:

1607:

1602:

1597:

1592:

1587:

1586:

1585:

1573:

1568:

1563:

1558:

1553:

1548:

1543:

1538:

1528:

1526:

1525:Other concepts

1522:

1521:

1519:

1518:

1513:

1508:

1503:

1498:

1493:

1488:

1482:

1480:

1474:

1473:

1470:

1469:

1467:

1466:

1461:

1456:

1451:

1446:

1441:

1436:

1430:

1428:

1421:

1420:

1411:

1410:

1409:

1399:

1397:Apocalypticism

1394:

1388:

1386:

1380:

1379:

1377:

1376:

1371:

1366:

1361:

1356:

1351:

1346:

1341:

1336:

1331:

1326:

1321:

1315:

1313:

1311:Trinitarianism

1307:

1306:

1303:

1302:

1300:

1299:

1285:

1280:

1274:

1272:

1268:

1267:

1265:

1264:

1259:

1254:

1249:

1244:

1238:

1236:

1232:

1231:

1229:

1228:

1226:Zoroastrianism

1223:

1218:

1213:

1208:

1203:

1202:

1201:

1196:

1191:

1186:

1175:

1173:

1166:

1158:

1157:

1154:

1153:

1151:

1150:

1145:

1144:

1143:

1130:

1125:

1120:

1117:

1115:

1111:

1110:

1108:

1107:

1102:

1097:

1092:

1087:

1082:

1077:

1072:

1067:

1062:

1061:

1060:

1058:Urmonotheismus

1050:

1045:

1040:

1035:

1030:

1025:

1020:

1015:

1012:

1010:

1003:

993:

992:

980:

979:

972:

971:

964:

957:

949:

943:

942:

936:

928:

925:

922:

921:

914:

896:

876:

869:

851:

844:

821:

814:

789:

767:

760:

733:

726:

699:

692:

663:

653:

647:. p. 61.

626:

598:

597:

595:

592:

591:

590:

584:

583:

567:

564:

515:

512:

511:

510:

506:

498:

497:

493:

489:

481:

480:

476:

472:

468:

465:

461:

457:

454:

450:

445:

442:

432:

429:

398:

395:

378:

377:

374:

371:

340:

337:

332:

329:

311:René Descartes

288:

287:

285:

284:

277:

270:

262:

259:

258:

255:

254:

249:

244:

242:Baruch Spinoza

239:

234:

228:

225:

224:

221:

220:

217:

216:

211:

206:

201:

196:

191:

186:

181:

175:

172:

171:

168:

167:

164:

163:

156:

149:

144:

139:

134:

129:

124:

119:

114:

109:

104:

99:

94:

89:

82:

80:Dream argument

77:

72:

67:

62:

57:

51:

48:

47:

44:

43:

35:

34:

32:René Descartes

28:

27:

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

2001:

1990:

1987:

1985:

1982:

1981:

1979:

1966:

1962:

1956:

1942:

1939:

1937:

1934:

1933:

1931:

1929:

1925:

1919:

1916:

1914:

1911:

1909:

1908:Denominations

1906:

1904:

1901:

1899:

1896:

1895:

1893:

1891:

1887:

1881:

1880:Last Judgment

1878:

1876:

1873:

1871:

1868:

1866:

1863:

1861:

1858:

1856:

1852:

1849:

1848:

1846:

1844:

1840:

1834:

1831:

1829:

1826:

1825:

1823:

1821:

1817:

1811:

1808:

1806:

1803:

1801:

1798:

1796:

1793:

1791:

1788:

1786:

1783:

1781:

1778:

1776:

1773:

1771:

1768:

1766:

1763:

1761:

1758:

1756:

1753:

1751:

1748:

1746:

1743:

1741:

1738:

1736:

1733:

1731:

1728:

1726:

1723:

1721:

1718:

1717:

1715:

1713:

1709:

1705:

1698:

1694:

1680:

1677:

1675:

1672:

1670:

1667:

1665:

1662:

1660:

1657:

1656:

1654:

1651:

1647:

1641:

1640:Unmoved mover

1638:

1636:

1633:

1631:

1628:

1626:

1623:

1621:

1618:

1616:

1613:

1611:

1608:

1606:

1603:

1601:

1598:

1596:

1593:

1591:

1588:

1583:

1579:

1578:

1577:

1574:

1572:

1569:

1567:

1564:

1562:

1559:

1557:

1554:

1552:

1549:

1547:

1544:

1542:

1541:Binitarianism

1539:

1537:

1533:

1530:

1529:

1527:

1523:

1517:

1514:

1512:

1509:

1507:

1504:

1502:

1499:

1497:

1494:

1492:

1489:

1487:

1484:

1483:

1481:

1479:

1475:

1465:

1462:

1460:

1457:

1455:

1452:

1450:

1447:

1445:

1442:

1440:

1437:

1435:

1432:

1431:

1429:

1425:

1419:

1415:

1412:

1408:

1405:

1404:

1403:

1400:

1398:

1395:

1393:

1390:

1389:

1387:

1385:

1381:

1375:

1372:

1370:

1367:

1365:

1362:

1360:

1357:

1355:

1352:

1350:

1347:

1345:

1342:

1340:

1337:

1335:

1332:

1330:

1327:

1325:

1322:

1320:

1317:

1316:

1314:

1312:

1308:

1297:

1293:

1289:

1286:

1284:

1281:

1279:

1276:

1275:

1273:

1269:

1263:

1262:Supreme Being

1260:

1258:

1255:

1253:

1250:

1248:

1245:

1243:

1240:

1239:

1237:

1233:

1227:

1224:

1222:

1219:

1217:

1214:

1212:

1209:

1207:

1204:

1200:

1197:

1195:

1192:

1190:

1187:

1185:

1182:

1181:

1180:

1177:

1176:

1174:

1170:

1167:

1163:

1159:

1149:

1146:

1142:

1139:

1138:

1137:

1134:

1133:Gender of God

1131:

1129:

1126:

1124:

1121:

1119:

1118:

1116:

1112:

1106:

1103:

1101:

1098:

1096:

1093:

1091:

1088:

1086:

1083:

1081:

1078:

1076:

1073:

1071:

1068:

1066:

1063:

1059:

1056:

1055:

1054:

1051:

1049:

1046:

1044:

1041:

1039:

1038:Kathenotheism

1036:

1034:

1031:

1029:

1026:

1024:

1021:

1019:

1016:

1014:

1013:

1011:

1007:

1004:

1002:

998:

994:

990:

985:

981:

977:

970:

965:

963:

958:

956:

951:

950:

947:

941:

937:

935:

931:

930:

917:

915:0-521-63712-0

911:

907:

900:

892:

885:

883:

881:

872:

866:

862:

855:

847:

845:0-631-15046-3

841:

837:

830:

828:

826:

817:

815:0-394-30665-1

811:

806:

805:

796:

794:

777:

771:

763:

761:0-415-11193-5

757:

753:

746:

744:

742:

740:

738:

729:

727:0-521-24595-8

723:

719:

712:

710:

708:

706:

704:

695:

693:1-138-01918-6

689:

685:

678:

676:

674:

672:

670:

668:

660:

656:

654:9781623569808

650:

646:

642:

641:

636:

630:

615:

614:

609:

603:

599:

589:

586:

585:

581:

570:

562:

557:

553:

550:

546:

541:

538:

533:

528:

524:

520:

507:

503:

502:

501:

494:

490:

486:

485:

484:

477:

473:

469:

466:

462:

458:

455:

451:

448:

447:

441:

437:

428:

425:

424:

419:

418:

411:

407:

402:

394:

390:

386:

382:

375:

372:

369:

368:

367:

364:

361:

358:

354:

349:

344:

336:

328:

325:

321:

320:

314:

312:

308:

304:

301:

300:

295:

283:

278:

276:

271:

269:

264:

263:

261:

260:

253:

250:

248:

245:

243:

240:

238:

235:

233:

230:

229:

223:

222:

215:

212:

210:

207:

205:

202:

200:

197:

195:

192:

190:

187:

185:

182:

180:

177:

176:

170:

169:

162:

161:

157:

155:

154:

150:

148:

145:

143:

140:

138:

135:

133:

132:Rule of signs

130:

128:

125:

123:

120:

118:

115:

113:

110:

108:

105:

103:

100:

98:

95:

93:

90:

88:

87:

83:

81:

78:

76:

73:

71:

68:

66:

63:

61:

58:

56:

53:

52:

46:

45:

41:

37:

36:

33:

30:

29:

25:

21:

20:

1775:Hamartiology

1760:Ecclesiology

1750:Pneumatology

1659:Christianity

1650:Names of God

1625:Philo's view

1615:Personal god

1595:Great Spirit

1534: /

1491:Christianity

1349:Perichoresis

1252:Emanationism

1194:Christianity

1184:Baháʼí Faith

1162:Singular god

1135:

1095:Spiritualism

939:

933:

905:

899:

890:

860:

854:

835:

803:

780:. Retrieved

770:

751:

717:

683:

658:

639:

629:

617:. Retrieved

611:

602:

559:

554:

548:

544:

542:

536:

531:

529:

525:

521:

517:

499:

482:

438:

434:

422:

421:

416:

415:

412:

409:

404:

400:

391:

387:

383:

379:

365:

362:

359:

355:

351:

346:

342:

334:

318:

315:

297:

293:

291:

199:La Géométrie

158:

153:Res cogitans

151:

147:Wax argument

96:

84:

55:Cartesianism

1833:Krishnology

1810:Soteriology

1765:Eschatology

1745:Christology

1610:Open theism

1566:Exotheology

1464:Zoroastrian

1427:By religion

1384:Eschatology

1339:Homoiousian

1292:Ahura Mazda

1070:Panentheism

1033:Hermeticism

537:Meditations

492:comparison.

319:Meditations

160:Res extensa

60:Rationalism

1978:Categories

1918:Philosophy

1805:Sophiology

1785:Philosophy

1780:Messianism

1740:Paterology

1344:Hypostasis

1334:Homoousian

1165:theologies

1105:Theopanism

1090:Polytheism

1053:Monotheism

1028:Henotheism

594:References

92:Evil demon

49:Philosophy

1795:Practical

1790:Political

1755:Cosmology

1712:Christian

1571:Holocaust

1561:Egotheism

1516:Goddesses

1511:Mormonism

1439:Christian

1392:Afterlife

1278:Sustainer

1085:Polydeism

1080:Pantheism

1065:Mysticism

1048:Monolatry

1043:Nontheism

1023:Dystheism

891:Descartes

836:Descartes

488:infinite.

423:objective

189:The World

70:Mechanism

1913:Kabbalah

1860:Prophets

1735:Glossary

1701:By faith

1664:Hinduism

1546:Demiurge

1536:in Islam

1496:Hinduism

1486:Buddhism

1478:Feminist

1434:Buddhist

1242:Absolute

1235:Concepts

1211:Hinduism

1206:Buddhism

1172:By faith

1136:and gods

1128:Divinity

1114:Concepts

1075:Pandeism

976:Theology

637:(2013).

635:Gary Cox

566:See also

460:reality.

305:for the

303:argument

299:a priori

24:a series

22:Part of

1903:Aggadah

1851:Oneness

1843:Islamic

1725:Outline

1720:History

1679:Judaism

1674:Jainism

1630:Process

1605:Olelbis

1506:Judaism

1449:Islamic

1364:Trinity

1247:Brahman

1221:Sikhism

1216:Jainism

1189:Judaism

1141:Goddess

927:Sources

782:16 July

545:Replies

532:Replies

479:exists.

475:myself.

376:a mode.

316:In the

1941:Wiccan

1890:Jewish

1870:Angels

1800:Public

1770:Ethics

1459:Taoist

1454:Jewish

1414:Heaven

1271:God as

1001:Theism

912:

867:

842:

812:

758:

724:

690:

651:

619:May 2,

417:formal

296:is an

226:People

127:Folium

1928:Pagan

1820:Hindu

1669:Islam

1501:Islam

1444:Hindu

1407:Fitra

1257:Logos

1199:Islam

1148:Numen

1123:Deity

1018:Deism

1009:Forms

173:Works

1635:Tian

1418:Hell

1288:Good

1283:Time

910:ISBN

865:ISBN

840:ISBN

810:ISBN

784:2017

756:ISBN

722:ISBN

688:ISBN

649:ISBN

621:2023

292:The

1855:God

1853:of

549:qua

509:me.

1980::

1652:in

1416:/

1294:,

879:^

824:^

792:^

736:^

702:^

666:^

657:.

643:.

610:.

26:on

1298:)

1290:(

968:e

961:t

954:v

918:.

873:.

848:.

818:.

786:.

764:.

730:.

696:.

623:.

281:e

274:t

267:v

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.