155:

408:

700:

river abruptly arrived at a sharp bend, the boats would follow

Descartes third law of motion and hit the shore of the river since the flow of the particles in the river would not have enough force to change the direction of the boat. However, the much lighter floating debris would follow the river since the particles in the river would have sufficient force to change the direction of the debris. In the heavens, it’s the circular flow of celestial particles, or

711:. The particles of the aether have greater agitation than the particles of air, which in turn have greater agitation than the particles that compose terrestrial objects (e.g. stones). The greater agitation of the aether prevents the particles of air from escaping into the heavens, just as the agitation of air particles forces terrestrial bodies, whose particles have far less agitation than those of air, to descend towards the world.

36:

720:

Descartes believed nature was without a void. To illustrate this, Descartes used the example of a stick being pushed against some body. Just as the force which is felt at one end of the stick is instantly transferred and felt at the other end, so is the impulse of light that is sent across the heavens and through the atmosphere from luminous bodies to our eyes. Descartes attributed light to have 12 distinct properties:

624:

belief that such a relationship existed. Next he describes how fire is capable of breaking wood apart into its minuscule parts through the rapid motion of the particles of fire within the flames. This rapid motion of particles is what gives fire its heat, since

Descartes claims heat is nothing more

719:

With his laws of motion set forth and the universe operating under these laws, Descartes next begins to describe his theory on the nature of light. Descartes believed that light traveled instantaneously - a common belief at the time – as an impulse across all the adjacent particles in nature, since

690:

Descartes elaborates on how the universe could have started from utter chaos and with these basic laws could have had its particles arranged so as to resemble the universe we observe today. Once the particles in the chaotic universe began to move, the overall motion would have been circular because

628:

According to

Descartes, the motion, or agitation, of these particles is what gives substances their properties (i.e. their fluidity and hardness). Fire is the most fluid and has enough energy to render most other bodies fluid whereas the particles of air lack the force necessary to do the same.

699:

of the planets about the Sun with the heavier objects spinning out towards the outside of the vortex and the lighter objects remaining closer to the center. To explain this, Descartes used the analogy of a river that carried both floating debris (leaves, feathers, etc.) and heavy boats. If the

643:

Descartes describes substances as consisting only of three elementary elements: fire, air and earth, from which the properties of any substance can be characterized by its composition of these elements, the size and arrangement of the particles in the substance, and the motion of its particles.

619:

Before

Descartes begins to describe his theories in physics, he introduces the reader to the idea that there is no relationship between our sensations and what creates these sensations, thereby casting doubt on the

691:

there is no void in nature, so whenever a single particle moves, another particle must also move to occupy the space where the previous particle once was. This type of circular motion, or

515:

for "suspicion of heresy" and sentencing to house arrest. Descartes discussed his work on the book, and his decision not to release it, in letters with another philosopher,

154:

685:

659:“…when one of these bodies pushes another, it cannot give the 2nd any motion, except by losing as much of its own motion at the same time…”

938:

928:

656:“…each particular part of matter always continues in the same state unless collision with others forces it to change its state.”

536:(1644), a Latin textbook at first intended by Descartes to replace the Aristotelian textbooks then used in universities. In the

810:

298:

100:

17:

72:

707:

As to the reason why heavy objects on Earth fall, Descartes explained this through the agitation of the particles in the

662:“…when a body is moving…each of its parts individually tends always to continue moving along a straight line” (Gaukroger)

394:

293:

948:

469:

popular in the 17th century. He thought everything physical in the universe to be made of tiny "corpuscles" of matter.

79:

882:

119:

53:

485:

presents a corpuscularian cosmology in which swirling vortices explain, among other phenomena, the creation of the

318:

756:

11) and 12) The force of a ray can be augmented or diminished by the disposition of the matter that receives it.

86:

783:

57:

610:

That the Face of the Heaven of That New World Must Appear to Its

Inhabitants Completely like That of Our World

68:

933:

246:

231:

898:

652:

Descartes asserts several laws governing the motion of these particles and all other objects in nature:

852:

346:

540:

the heliocentric tone was softened slightly with a relativist frame of reference. The last chapter of

138:

481:, and all matter was constantly swirling to prevent a void as corpuscles moved through other matter.

361:

216:

918:

913:

668:

532:

323:

387:

308:

46:

840:, critical edition with an introduction and notes by Annie Bitbol-Hespériès, Paris: Seuil, 1996.

943:

637:

462:

184:

800:

592:

On the Origin and the Course of the

Planets and Comets in General; and of Comets in Particular

303:

221:

93:

923:

848:

328:

8:

478:

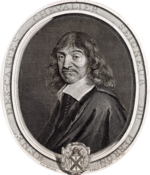

442:(1596–1650). Written between 1629 and 1633, it contains a nearly complete version of his

351:

241:

636:, Descartes deduced that all particles in nature are packed together such that there is

466:

380:

366:

211:

583:

Description of a New World, and on the

Qualities of the Matter of Which it is Composed

878:

871:

862:

806:

779:

673:

508:

470:

313:

256:

226:

439:

146:

267:

236:

200:

745:

If the rays are of very unequal force, then they can sometimes impede one another

701:

629:

Hard bodies have particles that are all equally hard to separate from the whole.

621:

431:

251:

189:

179:

577:

On the Void, and How it

Happens that Our Senses Are Not Aware of Certain Bodies

516:

356:

194:

907:

407:

739:

Several rays can start at the same point and travel in different directions

500:

486:

477:. The main difference was that Descartes maintained that there could be no

261:

169:

851:. New York: Abaris Books, 1979. (French and English text on facing pages)

568:

On the

Difference Between our Sensations and the Things That Produce Them

447:

274:

174:

742:

Several rays can pass through the same point without impeding each other

625:

than just the motion of particles, and what causes it to produce light.

708:

504:

443:

206:

736:

Several rays can come from different points and meet at the same point

35:

595:

On the

Planets in General, and in Particular on the Earth and Moon

802:

The Cambridge history of seventeenth-century philosophy: Volume I

512:

474:

455:

451:

873:

The Great Conversation: A Historical Introduction to Philosophy

696:

692:

633:

778:(Repr., paperback ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

753:

9) and 10) Rays can be diverted by reflection or by refraction

724:

Light extends radially in all direction from luminous bodies

556:

was finally published in 1664, and the entire text in 1677.

686:

Mechanical explanations of gravitation § Vortex Theory

632:

Based on his observations of how resistant nature is to a

589:

On the Formation of the Sun and the Stars of the New World

507:. Descartes delayed the book's release upon news of the

490:

704:, that causes the motion of the planets to be circular.

695:, would have created what Descartes observed to be the

614:

60:. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

870:

733:Light travels ordinarily in straight lines or rays

905:

868:

580:On the Number of Elements and on Their Qualities

489:and the circular motion of planets around the

865:. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

798:

388:

714:

503:view, first explicated in Western Europe by

805:. Cambridge University Press. p. 688.

647:

571:In What the Heat and Light of Fire Consists

395:

381:

773:

679:

120:Learn how and when to remove this message

559:

406:

586:On the Laws of Nature of this New World

14:

906:

58:adding citations to reliable sources

29:

776:Descartes an intellectual biography

294:Rules for the Direction of the Mind

24:

847:. Translation and introduction by

25:

960:

892:

845:Le Monde, ou Traite de la lumiere

727:Light extends out to any distance

939:Philosophy of science literature

615:The void and particles in nature

436:Traité du monde et de la lumière

153:

34:

929:Historical physics publications

526:was revised for publication as

319:Meditations on First Philosophy

45:needs additional citations for

792:

767:

601:On the Ebb and Flow of the Sea

13:

1:

853:Mahoney's English translation

830:

730:Light travels instantaneously

640:or empty space between them.

859:The World and Other Writings

544:was published separately as

7:

774:Gaukroger, Stephen (2004).

672:added to these his laws on

10:

965:

683:

607:On the Properties of Light

347:Christina, Queen of Sweden

869:Melchert, Norman (2002).

715:Cartesian theory on light

574:On Hardness and Liquidity

362:Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

217:Causal adequacy principle

760:

669:Principles of Philosophy

648:Cartesian laws of motion

533:Principles of Philosophy

324:Principles of Philosophy

949:Works by René Descartes

552:) in 1662. The rest of

309:Discourse on the Method

799:Daniel Garber (2003).

680:The Cartesian universe

528:Principia philosophiae

473:is closely related to

416:

27:Book by René Descartes

684:Further information:

463:mechanical philosophy

427:Treatise on the Light

410:

69:"The World" book

18:The World (Descartes)

849:Michael Sean Mahoney

329:Passions of the Soul

299:The Search for Truth

54:improve this article

522:Some material from

461:Descartes espoused

352:Nicolas Malebranche

222:Mind–body dichotomy

190:Doubt and certainty

934:Natural philosophy

467:natural philosophy

446:, from method, to

417:

367:Francine Descartes

212:Trademark argument

863:Stephen Gaukroger

857:Descartes, René.

843:Descartes, René.

838:Le Monde, L'Homme

836:Descartes, René,

812:978-0-521-53720-9

674:elastic collision

511:'s conviction of

509:Roman Inquisition

471:Corpuscularianism

405:

404:

257:Balloonist theory

232:Coordinate system

227:Analytic geometry

130:

129:

122:

104:

16:(Redirected from

956:

888:

876:

824:

823:

821:

819:

796:

790:

789:

771:

438:), is a book by

397:

390:

383:

237:Cartesian circle

201:Cogito, ergo sum

157:

134:

133:

125:

118:

114:

111:

105:

103:

62:

38:

30:

21:

964:

963:

959:

958:

957:

955:

954:

953:

919:1633 in science

914:1629 in science

904:

903:

895:

885:

877:. McGraw Hill.

833:

828:

827:

817:

815:

813:

797:

793:

786:

772:

768:

763:

717:

688:

682:

650:

617:

565:

401:

372:

371:

342:

334:

333:

289:

281:

280:

252:Cartesian diver

180:Foundationalism

165:

126:

115:

109:

106:

63:

61:

51:

39:

28:

23:

22:

15:

12:

11:

5:

962:

952:

951:

946:

941:

936:

931:

926:

921:

916:

902:

901:

899:Online version

894:

893:External links

891:

890:

889:

883:

866:

855:

841:

832:

829:

826:

825:

811:

791:

784:

765:

764:

762:

759:

758:

757:

754:

747:

746:

743:

740:

737:

734:

731:

728:

725:

716:

713:

681:

678:

664:

663:

660:

657:

649:

646:

616:

613:

612:

611:

608:

605:

602:

599:

596:

593:

590:

587:

584:

581:

578:

575:

572:

569:

564:

558:

517:Marin Mersenne

440:René Descartes

424:, also called

403:

402:

400:

399:

392:

385:

377:

374:

373:

370:

369:

364:

359:

357:Baruch Spinoza

354:

349:

343:

340:

339:

336:

335:

332:

331:

326:

321:

316:

311:

306:

301:

296:

290:

287:

286:

283:

282:

279:

278:

271:

264:

259:

254:

249:

244:

239:

234:

229:

224:

219:

214:

209:

204:

197:

195:Dream argument

192:

187:

182:

177:

172:

166:

163:

162:

159:

158:

150:

149:

147:René Descartes

143:

142:

128:

127:

42:

40:

33:

26:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

961:

950:

947:

945:

944:Physics books

942:

940:

937:

935:

932:

930:

927:

925:

922:

920:

917:

915:

912:

911:

909:

900:

897:

896:

886:

884:0-19-517510-7

880:

875:

874:

867:

864:

860:

856:

854:

850:

846:

842:

839:

835:

834:

814:

808:

804:

803:

795:

787:

781:

777:

770:

766:

755:

752:

751:

750:

744:

741:

738:

735:

732:

729:

726:

723:

722:

721:

712:

710:

705:

703:

698:

694:

687:

677:

675:

671:

670:

666:Descartes in

661:

658:

655:

654:

653:

645:

641:

639:

635:

630:

626:

623:

609:

606:

603:

600:

597:

594:

591:

588:

585:

582:

579:

576:

573:

570:

567:

566:

563:

557:

555:

551:

547:

543:

539:

535:

534:

529:

525:

520:

518:

514:

510:

506:

502:

499:rests on the

498:

494:

492:

488:

484:

480:

476:

472:

468:

464:

459:

457:

453:

449:

445:

441:

437:

433:

429:

428:

423:

422:

414:

409:

398:

393:

391:

386:

384:

379:

378:

376:

375:

368:

365:

363:

360:

358:

355:

353:

350:

348:

345:

344:

338:

337:

330:

327:

325:

322:

320:

317:

315:

312:

310:

307:

305:

302:

300:

297:

295:

292:

291:

285:

284:

277:

276:

272:

270:

269:

265:

263:

260:

258:

255:

253:

250:

248:

247:Rule of signs

245:

243:

240:

238:

235:

233:

230:

228:

225:

223:

220:

218:

215:

213:

210:

208:

205:

203:

202:

198:

196:

193:

191:

188:

186:

183:

181:

178:

176:

173:

171:

168:

167:

161:

160:

156:

152:

151:

148:

145:

144:

140:

136:

135:

132:

124:

121:

113:

110:November 2011

102:

99:

95:

92:

88:

85:

81:

78:

74:

71: –

70:

66:

65:Find sources:

59:

55:

49:

48:

43:This article

41:

37:

32:

31:

19:

872:

858:

844:

837:

816:. Retrieved

801:

794:

775:

769:

748:

718:

706:

689:

667:

665:

651:

642:

631:

627:

622:Aristotelian

618:

561:

560:Contents of

553:

549:

545:

541:

537:

531:

527:

523:

521:

501:heliocentric

496:

495:

487:Solar System

482:

465:, a form of

460:

435:

426:

425:

420:

419:

418:

412:

314:La Géométrie

273:

268:Res cogitans

266:

262:Wax argument

199:

170:Cartesianism

131:

116:

107:

97:

90:

83:

76:

64:

52:Please help

47:verification

44:

924:1630s books

448:metaphysics

411:Descartes'

275:Res extensa

175:Rationalism

908:Categories

831:References

785:0198237243

709:atmosphere

538:Principles

505:Copernicus

444:philosophy

207:Evil demon

164:Philosophy

80:newspapers

861:. Trans.

598:On Weight

562:The World

554:The World

546:De Homine

542:The World

524:The World

497:The World

483:The World

421:The World

304:The World

185:Mechanism

818:27 April

604:On Light

413:Le Monde

139:a series

137:Part of

638:no void

513:Galileo

475:atomism

456:biology

452:physics

434:title:

94:scholar

881:

809:

782:

749:Also:

702:aether

697:orbits

693:vortex

634:vacuum

550:On Man

479:vacuum

432:French

415:, 1664

341:People

242:Folium

96:

89:

82:

75:

67:

761:Notes

450:, to

288:Works

101:JSTOR

87:books

879:ISBN

820:2013

807:ISBN

780:ISBN

454:and

73:news

530:or

491:Sun

56:by

910::

676:.

519:.

493:.

458:.

141:on

887:.

822:.

788:.

548:(

430:(

396:e

389:t

382:v

123:)

117:(

112:)

108:(

98:·

91:·

84:·

77:·

50:.

20:)

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.