235:

Physiology in Munich from 1857 onwards. After numerous successful audiences with two of the kings of

Bavaria he had helped found the first three hygiene departments. In 1879 he finally achieved his goal of the creation of a standalone Institute of Hygiene in Munich. This institution was larger than his previous accommodations in the department of Physiology and allowed him to continue to his research and to gather a large cohort of research students under his teachings. The founding of his Institute of Hygiene drew significant international attention and was considered a model for many later institutions including the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health in Baltimore.

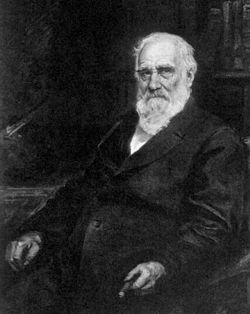

207:

research-oriented field. He is further responsible for the acceptance of hygiene as a science to be examined in medical schools and to be taught in specific hygiene departments. In 1865 his petitions to the government were accepted and three departments of hygiene were established in Munich, Würzburg, and

Erlangen. By 1882 hygiene was included in examinations for medical students in every major city of Germany. As one of the principal proponents for the field of hygiene in Munich he was responsible for giving presentations to government officials in order to secure funding for public health projects.

329:

219:

food production system used in Munich. He argued that the system for the study of proper cattle feed was more well developed than that for humans and recommended civic funding for studying proper nutrition. He proposed that this study of nutrition was important specifically for the poor and those in strictly controlled environments such as prison because they were most at risk for obtaining sub-par nutrition due to their limited control over their food consumption.

112:

33:

738:

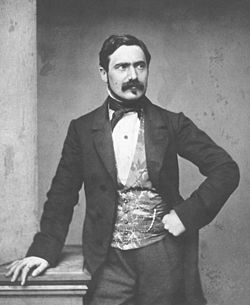

242:. During his career Koch identified and isolated a large number of bacterial strains and was a supporter of the theory that these germs were the main causes of disease. This placed him at odds with Pettenkofer's broader approach to disease that involved many other environmental factors in addition to the activity of the germ of a disease. The two scientists conflicted most notably over the subject of

63:

including: personal state of health, the fermentation of environmental ground water, and also the germ in question. He was most well known for his establishment of hygiene as an experimental science and also was a strong proponent for the founding of hygiene institutes in

Germany. His work served as an example which other institutes around the world emulated.

147:. This work derived from his position at the Munich mint and was centered around minimizing the costs of currency conversion by separating the precious metals from one another. The purer elements could then be utilized in other applications. Later in his career he continued published and spoke about the numerical relations between the

231:. He was also a strong proponent of regular bathing and changing of clothes in its relationship to health through the further regulation of the heat of the body. He advocated that health was the collective responsibility of a city to behave as best they are able to further the health of the general population.

222:

He further advocated for the construction of more spacious living accommodations. He asserted that there was a strong link between proper circulation of "good air" through houses, adequate space for living, and the health of the occupants. His beliefs aligned significantly with the school of thought

264:

to neutralise his stomach acid to counter a suggestion by Koch that the acid could kill the bacteria. Pettenkofer suffered mild symptoms for nearly a week but claimed these were not associated with cholera. The modern view is that he did indeed have cholera, but was lucky to just have a mild case

210:

One of the prevailing arguments of the day that

Pettenkofer focused on was the relationship between sewage and the health of a population. In one of his first major projects in his home city of Munich Pettenkofer advocated for the development of running water throughout the city. He also emphasized

62:

disposal. He was further known as an anti-contagionist, a school of thought, named later on, that did not believe in the then novel concept that bacteria were the main cause of disease. In particular he argued in favor of a variety of conditions collectively contributing to the incidence of disease

218:

where he applied his study of chemistry to the study of chemical reactions occurring within the body. This in particular focused on the study of the science of nutrition and the reactions in the body that consumed foods and produced the processes of the body. He further advocated for reform of the

227:. He firmly believed that the causes of disease were related to the multitude of environmental factors that the people of Munich were required to live in. Air was of a particular interest to him and he continued to advocate for its relevance to the processes of disease, specifically the spread of

159:. He rejected the current theory of triads and expanded the connections between the elements to larger groupings. He argued that the weights of different elements in a group were separated by multiples of a certain number that varied based upon the group. His work in this area was later cited by

356:

During his lifetime he received numerous accolades. He was presented with the title of "Honorary

Citizen" of Munich and given a gold medal. His work in hygiene precipitated the creation of the "Pettenkofer Foundation for Research in Hygiene" which received funding from the cities of Munich and

234:

In addition to the wide number of publications and lectures that he gave on the subject of public health

Pettenkofer was also involved in the initiative to create an Institute of Public Health in Munich. He continued research into a variety of fields listed above as head of the Institute of

206:

disposal. His attention was drawn to this subject by the unhealthy condition in Munich in the 19th century. Specifically he examined the field of hygiene and determined that there was a minimal amount of rigorous research. He was responsible for transitioning the field of hygiene into a

285:

from 1883 to 1894. In addition to his research publications he also gave a significant number of lectures to government officials in order to persuade them to provide funding for civic works and governmental oversight committees to promote and assess the state public health.

91:. After a falling out with a relative he was staying with he briefly entered the theater. He returned to his family to marry Helene Pettenkofer. A stipulation of his marriage was that he pursue another career and was advised to pursue medicine. He attended the

211:

the selection of the

Mangfall River, not the readily at hand and highly polluted Isar River, as the source of the city's drinking water. Many of his additions and plans for the city's sewage system are reflected today in the current sewage system layout.

127:, Pettenkofer was appointed chemist to the Munich mint in 1845. Two years later he was chosen as an extraordinary professor of chemistry at the medical faculty. In 1853 he was made a full professor and in 1865 he also became a professor of

167:

glass, the manufacture of illuminating gas from wood, the preservation of oil paintings, and an improved process for cement production among other things. The color-forming reaction known by his name for the detection of

517:, M. Ueber einen antiken rothen Glasfluss (Haematinon) und über Aventurin-Glas. Abhandlungen der naturw.-techn. Commission der k. b. Akad. der Wissensch. I. Bd. München, literar.-artist. Anstalt, 1856.

753:

842:

882:

847:

135:, both theoretical and applied, publishing papers on a wide range of topics. One of his first projects and subsequent publications was in the separation of

877:

163:

in his construction of the

Periodic Table of Elements. He continued his publications in a wide variety of other fields as well including: the formation of

702:

457:

791:

367:

317:

370:. Twenty-three pioneers of public health and tropical medicine were chosen to feature on the School's building when it was constructed in 1929.

677:

872:

867:

309:. In the same magazine, Pettenkofer is recognized to have developed an accurate quantitative analysis method for determining atmospheric

758:

238:

During his career his position as a strong proponent of public health at times placed him at odds with his contemporaries, most notably

202:

Pettenkofer's name is most familiar in connection with his work in practical hygiene, as an apostle of good water, fresh air and proper

316:

The 1899 handwritten manuscript 'On the self purification of rivers' and

Pettenkofer's papers can be found at the archives of the

862:

852:

502:

17:

257:

256:, the proponent of the theory that the bacterium was the sole cause of the disease. He consumed the bouillon in a

857:

632:

273:

Pettenkofer published his views on hygiene and disease in numerous books and papers; he was an editor of the

773:

100:

710:

92:

661:

645:

778:

294:

58:. He is known for his work in practical hygiene, as an apostle of good water, fresh air and proper

892:

494:

799:"Epidemics in Western Society Since 1600: Lecture 13 — Contagionism versus Anticontagionism"

360:

In 1883 he was awarded a hereditary title of nobility and was given the title "Excellency."

837:

832:

72:

345:

87:

to the

Bavarian court and was the author of some chemical investigations on the vegetable

8:

887:

544:"Max von Kettenkoffer (1818–1901) as a Pioneer of Modern Hygiene and Preventive Medicine"

337:

336:

In 1894 he retired from active work, and on 10 February 1901 he shot himself in a fit of

290:

261:

787:

783:

593:"The rise and fall of Munich's early modern water network: a tale of prowess and power"

568:

543:

487:

172:

was published in 1844. In his widely used method for the quantitative determination of

628:

573:

498:

363:

In 1897 he was awarded the Harlen Medal from the British Institute of Public Health.

306:

215:

604:

563:

555:

341:

189:

160:

152:

798:

810:

302:

248:

246:. In one specific case, Pettenkofer obtained bouillon laced with a large dose of

310:

156:

609:

592:

826:

749:

744:

537:

535:

533:

531:

529:

527:

525:

523:

278:

224:

173:

591:

Winiwater, Verena; Haidvogl, Gertrud; Bürkner, Michael (26 September 2016).

815:

577:

520:

253:

239:

185:

148:

493:(1 ed.). New York, New York: Oxford University Press Inc. pp.

357:

Leipzig to fund research projects related to Hygiene and Public Health.

559:

181:

164:

111:

84:

76:

32:

260:

in the presence of several witnesses on 7 October 1892. He also took

177:

169:

132:

124:

298:

144:

88:

79:. He was a nephew of Franz Xaver (1783–1850), who from 1823 was a

743:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the

427:

425:

423:

421:

243:

228:

188:. He further provided the experimental proof that the mysterious

128:

80:

55:

51:

48:

419:

417:

415:

413:

411:

409:

407:

405:

403:

401:

366:

Max Joseph von Pettenkofer's name features on the Frieze of the

394:(Third ed.). New York: Wiley and Putnam. pp. 138–139.

328:

203:

140:

120:

96:

59:

678:"Max Von Pettenkofer's collection entry at the LSHTM Archives"

625:

Who Goes First?: The Story of Self-experimentation in Medicine

480:

478:

398:

762:. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

265:

and he possibly had some immunity from a previous episode.

136:

475:

590:

332:

Pettenkofer's name of the LSHTM Frieze in Keppel Street

703:"Behind the Frieze – Max von Pettenkofer (1818–1901)"

194:

of ancient times was in fact a copper-colored glass.

155:. His theories were early in the development of the

584:

666:. Munn & Company. 16 January 1869. p. 39.

627:, pp. 24–25, University of California Press, 1987

489:The Periodic Table: Its Story and Its Significance

486:

385:

383:

843:People educated at the Wilhelmsgymnasium (Munich)

214:During his schooling he studied for a time under

824:

436:. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 3.

368:London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

318:London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

176:the gaseous mixture is shaken up with baryta or

792:Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

431:

380:

883:Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

848:Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich alumni

707:Archive version of LSHTM Library and Archives

305:is always detectable in the sick and dead as

131:. In his earlier years he devoted himself to

548:Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine

99:, then studied pharmacy and medicine at the

878:Members of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences

66:

47:(3 December 1818 – 10 February 1901) was a

784:Picture, short biography, and bibliography

542:Locher, Wolfgang Gerhard (November 2007).

389:

301:leaks in public spaces, noting endogenous

71:Pettenkofer was born in Lichtenheim, near

27:Bavarian chemist and hygienist (1818–1901)

608:

567:

748:

650:. Munn & Company. 1883. p. 147.

327:

110:

31:

796:

14:

825:

541:

484:

197:

451:

449:

447:

445:

443:

180:of known strength and the change in

106:

774:Pettenkofer School of Public Health

103:, where he graduated M.D. in 1845.

24:

868:People from Neuburg-Schrobenhausen

455:

25:

904:

767:

440:

873:Burials at the Alter Südfriedhof

736:

281:) from 1865 to 1882, and of the

695:

670:

654:

344:in Munich. He is buried in the

268:

863:Suicides by firearm in Germany

638:

617:

511:

351:

13:

1:

434:The Value of Health to a City

432:von Pettenkofer, Max (1941).

373:

340:. He died at his home in the

853:19th-century German chemists

101:Ludwig Maximilian University

7:

754:Pettenkofer, Max Joseph von

458:"Max Josef von Pettenkofer"

390:von Liebig, Justus (1848).

10:

909:

779:Audio version of this page

45:Max Joseph von Pettenkofer

610:10.1007/s12685-016-0173-y

295:carbon monoxide poisoning

811:"Max Joseph Pettenkofer"

323:

289:Pettenkofer appeared in

275:Zeitschrift für Biologie

184:ascertained by means of

67:Early life and education

797:Snowden, Frank (2010).

759:Encyclopædia Britannica

858:Germ theory denialists

333:

116:

115:Max Joseph Pettenkofer

43:, ennobled in 1883 as

41:Max Joseph Pettenkofer

37:

36:Max Joseph Pettenkofer

485:Scerri, Eric (2007).

331:

114:

35:

623:Lawrence K. Altman,

119:After working under

73:Neuburg an der Donau

713:on 11 February 2017

663:Scientific American

647:Scientific American

293:in 1883 discussing

291:Scientific American

262:bicarbonate of soda

198:Career as hygienist

18:Max von Pettenkofer

805:. Yale University.

788:Virtual Laboratory

560:10.1007/BF02898030

334:

283:Archiv für Hygiene

117:

38:

803:Open Yale Courses

504:978-0-19-530573-9

346:Alter Südfriedhof

307:carboxyhemoglobin

216:Justus von Liebig

107:Career as chemist

93:Wilhelmsgymnasium

16:(Redirected from

900:

819:

806:

763:

742:

740:

739:

723:

722:

720:

718:

709:. Archived from

699:

693:

692:

690:

688:

674:

668:

667:

658:

652:

651:

642:

636:

621:

615:

614:

612:

588:

582:

581:

571:

539:

518:

515:

509:

508:

492:

482:

473:

472:

470:

468:

462:encyclopedia.com

456:Dolman, Claude.

453:

438:

437:

429:

396:

395:

392:Animal Chemistry

387:

161:Dmitri Mendeleev

21:

908:

907:

903:

902:

901:

899:

898:

897:

823:

822:

809:

770:

752:, ed. (1911). "

737:

735:

727:

726:

716:

714:

701:

700:

696:

686:

684:

676:

675:

671:

660:

659:

655:

644:

643:

639:

622:

618:

589:

585:

540:

521:

516:

512:

505:

483:

476:

466:

464:

454:

441:

430:

399:

388:

381:

376:

354:

326:

303:carbon monoxide

297:resulting from

277:(together with

271:

249:Vibrio cholerae

200:

109:

69:

28:

23:

22:

15:

12:

11:

5:

906:

896:

895:

890:

885:

880:

875:

870:

865:

860:

855:

850:

845:

840:

835:

821:

820:

807:

794:

781:

776:

769:

768:External links

766:

765:

764:

750:Chisholm, Hugh

732:

731:

725:

724:

694:

682:LSHTM Archives

669:

653:

637:

616:

603:(3): 277–299.

583:

554:(6): 238–245.

519:

510:

503:

474:

439:

397:

378:

377:

375:

372:

353:

350:

325:

322:

311:carbon dioxide

270:

267:

252:bacteria from

199:

196:

157:Periodic Table

108:

105:

75:, now part of

68:

65:

26:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

905:

894:

893:1901 suicides

891:

889:

886:

884:

881:

879:

876:

874:

871:

869:

866:

864:

861:

859:

856:

854:

851:

849:

846:

844:

841:

839:

836:

834:

831:

830:

828:

818:

817:

812:

808:

804:

800:

795:

793:

789:

785:

782:

780:

777:

775:

772:

771:

761:

760:

755:

751:

746:

745:public domain

734:

733:

729:

728:

712:

708:

704:

698:

683:

679:

673:

665:

664:

657:

649:

648:

641:

634:

630:

626:

620:

611:

606:

602:

598:

597:Water History

594:

587:

579:

575:

570:

565:

561:

557:

553:

549:

545:

538:

536:

534:

532:

530:

528:

526:

524:

514:

506:

500:

496:

491:

490:

481:

479:

463:

459:

452:

450:

448:

446:

444:

435:

428:

426:

424:

422:

420:

418:

416:

414:

412:

410:

408:

406:

404:

402:

393:

386:

384:

379:

371:

369:

364:

361:

358:

349:

347:

343:

339:

330:

321:

319:

314:

312:

308:

304:

300:

296:

292:

287:

284:

280:

279:Carl von Voit

276:

266:

263:

259:

255:

251:

250:

245:

241:

236:

232:

230:

226:

225:Miasma theory

223:known as the

220:

217:

212:

208:

205:

195:

193:

192:

187:

183:

179:

175:

174:carbonic acid

171:

166:

162:

158:

154:

151:of analogous

150:

149:atomic masses

146:

142:

138:

134:

130:

126:

122:

113:

104:

102:

98:

94:

90:

86:

82:

78:

74:

64:

61:

57:

53:

50:

46:

42:

34:

30:

19:

816:FamilySearch

814:

802:

757:

715:. Retrieved

711:the original

706:

697:

685:. Retrieved

681:

672:

662:

656:

646:

640:

624:

619:

600:

596:

586:

551:

547:

513:

488:

465:. Retrieved

461:

433:

391:

365:

362:

359:

355:

335:

315:

288:

282:

274:

272:

269:Publications

247:

237:

233:

221:

213:

209:

201:

190:

118:

70:

44:

40:

39:

29:

838:1901 deaths

833:1818 births

730:Attribution

717:19 February

687:10 February

352:Recognition

348:in Munich.

254:Robert Koch

240:Robert Koch

186:oxalic acid

888:Hygienists

827:Categories

633:0520212819

374:References

338:depression

191:haematinum

182:alkalinity

170:bile acids

165:aventurine

85:apothecary

77:Weichering

258:self-test

178:limewater

133:chemistry

89:alkaloids

56:hygienist

578:21432069

342:Residenz

299:coal gas

153:elements

145:platinum

49:Bavarian

790:of the

786:in the

747::

569:2723483

467:3 March

244:cholera

229:cholera

129:hygiene

81:surgeon

52:chemist

741:

631:

576:

566:

501:

204:sewage

143:, and

141:silver

125:Gießen

121:Liebig

97:Munich

60:sewage

495:50–52

324:Death

95:, in

719:2018

689:2017

629:ISBN

574:PMID

499:ISBN

469:2017

137:gold

83:and

54:and

756:".

605:doi

564:PMC

556:doi

123:at

829::

813:,

801:.

705:.

680:.

599:.

595:.

572:.

562:.

552:12

550:.

546:.

522:^

497:.

477:^

460:.

442:^

400:^

382:^

320:.

313:.

139:,

721:.

691:.

635:.

613:.

607::

601:8

580:.

558::

507:.

471:.

20:)

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.