117:

keep his treasure save during his absence. However, instead of guarding it as promised, Salomo III soon spread a rumour about Hatto’s death and took possession of his treasure. Whereas he donated most of it to the poor and gifted another part to the

Minster of Constance, he also incorporated part of the treasure, for instance the two ivory plates, into the Saint Gall monastery treasure. Then he commissioned his most talented artist, the monk Tuotilo († 913) with the adornment of the plates and the monk Sintram, who was known to be a talented penman, to write an evangeliary.

101:

139:

218:

20:

235:

Ekkehard, were painted and gilded by Abbot Salomo himself. However, on closer examination, the initials were evidently created by the same hand as the rest of the manuscript, namely by

Sintram’s. As Anton von Euw remarks, Ekkehard’s comment thus has to be interpreted as an empty phrase of praise (dt. “Ruhmesfloskel”) for the benefit of Abbot Salomo.

225:

The text of the

Evangelium longum was written by the monk Sintram, of whom Ekkehard says that "his fingers were admired by all the world" and that his "elegant writing’s consistency is captivating". Johannes Duft and Rudolf Schnyder likewise comment on the "admirably uniform, astonishingly steady and

271:

Nowadays, the interior of the manuscript is still in surprisingly good condition, which indicates, according to Anton von Euw, that it was never or only rarely been opened. In contrast, Duft and

Schnyder remark that the cover of the Evangelium longum has experienced at least two restorations. Before

251:

From pages 6 to 10, the

Evangelium longum recounts the first chapter of the Gospel of Matthew, including Jesus’s lineage and his birth from the Virgin Mary. Page 10, which displays the initials "I" and "C" as well as the capitals INCIPIVNT LECTIONES EVANGELIOR PER ANNI CIRCVLVM LEGENDAE, commences a

275:

Several factors distinguish the oblong evangeliary that is being kept in Saint Gall. Firstly, the

Evangelium longum was definitely produced not only as another book, but as a showpiece evangeliary. Thus, Ekkehard writes that it is a one of a kind evangeliary, "of which in our opinion there will not

199:

and the bear, the most familiar part of Saint Gall’s founding myth. At the top, the back plate also exhibits an ornamental part and the three parts are again divided by bars. The inscription on the upper bar says ASCENSIO SCE MARIE ("The

Assumption of the holy Mary"), whereas the inscription on the

120:

As

Johannes Duft and Rudolf Schnyder explain, for a long time it was falsely believed that Tuotilo had only ornamented one of the two plates, as Ekkehard writes in his report that "one of these was delightfully adorned with imagery; the other was of most delicate smoothness, and precisely that one

238:

When including the two mirror blades attached to the front and back book cover as well as the two endpapers, the

Evangelium longum consists of 154 parchment sheets. Beginning at the first endpaper, the sheets were paginated by the abbey librarian Ildefons von Arx with Arabic numbers (1-304) in red

203:

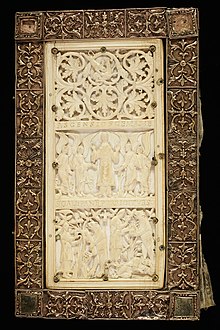

The two ivory plaques are placed in an oak wood frame, which is mounted with fittings made of precious metal. The creation of this frame, embellished with gold and jewels from Bishop Hatto’s treasure, can also be ascribed to the monk

Tuotilo. According to new research, the metal on the front plate

116:

as writing pads, were probably bequeathed by the Emperor to the archbishopric of Mainz and thence came into the possession of Hatto, at that time Archbishop of Mainz (891–913). When Hatto had to accompany King Arnulf (850-899) to Italy, he asked his friend, Abbot Salomo of Saint Gall (890-920), to

88:

investigation, the date when a tree was felled is calculated by means of its growth rings. Such an examination was conducted on the wooden parts of the book cover in the 1970s. Dating to the year 894 is confirmed by a tale about the origin of the Evangelium longum that was written around 1050 and

124:

The Evangelium longum, whose name is derived from its extraordinary oblong format, was supposed to serve as a showpiece evangeliary (dt. “Prachtevangelistar”) for important events such as the major church festivals or the arrival of guests of high-rank. Interestingly, the pericopes that form the

234:

in and for Saint Gall. Every sentence in the Evangelium longum begins with a golden painted capital letter resulting in a total of twenty to thirty of these capitals per page. On some pages there are moreover golden initials, two of which, namely the "L" and "C" on pages 7 and 11, according to

247:

The Evangelium longum contains the gospel-pericopes which were supposed to be sung by the deacon during mass. Pages 6 and 7 are adorned with two magnificent initials: While page 6 exhibits the golden and silver painted initial "I" and the capitals IN EXPORTV SCE GENITRICIS D MARIAE, page 7 is

146:

The crucial element of the Evangelium longum’s cover are the two ivory plaques that were carved by Tuotilo. Now as then, their size is considered extraordinary. Ekkehard writes that the plaques are of a dimension, "as if the elephant furnished with such teeth had been a giant compared to his

272:

1461, the bindings of the book block were restored, the book spine replaced and the golden applications on the front plate repaired. Probably in the 18th century, another restoration was conducted, in the course of which the book spine as well as the front gold lining were again renovated.

188:. The narrative picture field in the middle of the plate is framed by ornamental parts above and below that are separated by two bars. The bars bear the following inscription: HIC RESIDET XPC VIRTVTVM STEMMATE SEPTVS (Here Christ sits enthroned, surrounded by the wreath of virtues).

208:

in Chapter 74 which says that in the year 954, at the reception of Abbot Craloh at the abbey, a monk did not want to present the Evangelium longum to his abbot to kiss. Instead he threw it towards him, whereby it fell to the ground and the front side was damaged.

112:, Ekkehard comments on these plates as follows: "These were, however, former wax tablets to write on, like the ones that Charlemagne, according to his biographer, usually placed beside his bed when he went to sleep". These plates, which were formerly used by

256:, i.e. for the feasts of the Lord as well as for all the Sundays, including Wednesday and Friday, of the church year. A short appendix furthermore entails pericopes for Trinity Sunday and the votive masses from Monday to Saturday.

279:

The material value left aside, the Evangelium longum is moreover one of the manuscripts whose development history is the most closely documented (from before 900 until today), which makes it a work of the highest documentary value.

283:

Finally, the Evangelium longum symbolises, according to David Ganz, the connection of Saint Gall’s monastery chronicle to the court of Charlemagne as well as the then close bond between the abbey and the Archbishopric of Mainz.

168:(John, Matthew, Mark and Lucas) are depicted, while their symbols (eagle, winged man, lion and bull) are situated directly around Christ. According to Anton von Euw, the four evangelists represent the "Quadriga Virtutum" from

71:

and can be found in the Codex Sangallensis under Cod. 53. It belongs to the permanent exhibition of the abbey library. It is available online as part of the “e-codices”-project of the University of Fribourg.

259:

On page 234, the second part of the Evangelium longum begins with the inscription INCIPIVNT LECTIONES EVANGELIOR DE SINGVLIS FESTIVITATIBVS SCORVM. Pages 234 to 290 thus consist of the so-called

164:

in his right hand. An alpha and an omega are engraved on both sides of his head. Moreover, Christ is flanked by two Seraphs as well as lighthouses with torches. In the corners of the frame, the

121:

Salomo gave Tuotilo to carve". Examinations with regard to the age of the carvings revealed, however, that they derive from the same time and the same hand, namely that of Tuotilo.

84:. Not only are the patron and the artists that were involved in its creation known by name, but also the year of production of the manuscript can be exactly determined. During a

720:

239:

ink. The average size of a page is 395 x 230 mm, the written space measures 275 x 145/165 mm and each written page consists of 29 lines.

725:

108:

The story of the manuscript begins with the ivory plaques measuring over 500 cm that were incorporated into the book cover. In the

710:

172:

Doctrine of Virtue on whom man is supposed to soar up to the throne of heaven. Finally, the sun and the moon, personified by

695:

252:

new part of the text: pages 11 to 233 contain the pericopes taken from the gospels which are used for the so-called

248:

inscribed with the bright golden capitals INITIV SCI EUANG SEDM MATHEV und LIBER GENERATIONIS IHV XPI.

180:, are depicted at the upper border of the image, while at the bottom, the ocean and the earth are represented by

230:

that was typically used in Saint Gall in the 9th century. Abbot Hartmut (872-883) himself developed this late

715:

68:

204:

was replaced in the 10th century. This fact could be connected to an episode reported in Ekkehard’s

191:

The back plaque (320 x 154 mm, 9 to 10 mm thick), also called “Gall plate”, depicts the

221:

Text page of the Evangelium longum (p. 8) with golden capitals at the beginning of every sentence

32:

231:

173:

226:

even hand". The pages were carefully ruled with a stylus and inscribed with the so-called

8:

150:

The front plaque of the Evangelium longum (320 x 155 mm, 9 to 12 mm thick) has

42:

200:

lower bar reads S GALL PANE PORRIGIT URSO (Saint Gallus hands some bread to the bear).

192:

684:

185:

151:

165:

85:

57:

100:

138:

217:

177:

696:

St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 53: Evangelium longum (Evangelistary)

704:

147:

conspecifics". Pieces of bone were used in order to mend holes in the ivory.

60:, a cover with carved ivory plaques and metal fittings, was made by the monk

161:

263:, meaning the pericopes for the feasts of the saints of the church year.

113:

94:

81:

46:

38:

19:

196:

266:

16:

Illuminated manuscript made in the Abbey of Saint Gail in Switzerland

335:

156:

80:

The Evangelium longum is arguably the best documented book of the

641:

Die St. Galler Buchkunst vom 8. bis zum Ende des 11. Jahrhunderts

599:

Die St. Galler Buchkunst vom 8. bis zum Ende des 11. Jahrhunderts

557:

Die St. Galler Buchkunst vom 8. bis zum Ende des 11. Jahrhunderts

473:

Die St. Galler Buchkunst vom 8. bis zum Ende des 11. Jahrhunderts

375:

Die St. Galler Buchkunst vom 8. bis zum Ende des 11. Jahrhunderts

316:

Die St. Galler Buchkunst vom 8. bis zum Ende des 11. Jahrhunderts

181:

125:

content of the book, were created for the cover, not vice versa.

61:

50:

169:

35:

543:

Hundert Kostbarkeiten aus der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

361:

Hundert Kostbarkeiten aus der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

309:

Hundert Kostbarkeiten aus der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

336:"e-codices - Virtual Manuscript Library of Switzerland"

655:

Die Elfenbein-Einbände der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

613:

Die Elfenbein-Einbände der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

585:

Die Elfenbein-Einbände der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

571:

Die Elfenbein-Einbände der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

529:

Die Elfenbein-Einbände der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

515:

Die Elfenbein-Einbände der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

501:

Die Elfenbein-Einbände der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

487:

Die Elfenbein-Einbände der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

459:

Die Elfenbein-Einbände der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

417:

Die Elfenbein-Einbände der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

403:

Die Elfenbein-Einbände der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

295:

Die Elfenbein-Einbände der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen

267:Subsequent history and relevance of the manuscript

67:Today, the original evangeliary is located in the

307:Schmuki, Karl, Peter Ochsenbein und Cornel Dora:

702:

721:Manuscripts of the Abbey library of Saint Gall

615:. Beuroner Kunstverlag. 1984. pp. 90–92.

587:. Beuroner Kunstverlag. 1984. pp. 55–56.

517:. Beuroner Kunstverlag. 1984. pp. 57–58.

669:Buchgewänder: Prachteinbände im Mittelalter

627:Buchgewänder: Prachteinbände im Mittelalter

445:Buchgewänder: Prachteinbände im Mittelalter

431:Buchgewänder: Prachteinbände im Mittelalter

389:Buchgewänder: Prachteinbände im Mittelalter

302:Buchgewänder: Prachteinbände im Mittelalter

104:Front of the cover of the Evangelium longum

643:. Verlag am Klosterhof. 2008. p. 163.

601:. Verlag am Klosterhof. 2008. p. 165.

559:. Verlag am Klosterhof. 2008. p. 167.

475:. Verlag am Klosterhof. 2008. p. 159.

377:. Verlag am Klosterhof. 2008. p. 156.

142:Back of the cover of the Evangelium longum

657:. Beuroner Kunstverlag. 1984. p. 93.

573:. Beuroner Kunstverlag. 1984. p. 55.

545:. Verlag am Klosterhof. 1998. p. 94.

531:. Beuroner Kunstverlag. 1984. p. 57.

503:. Beuroner Kunstverlag. 1984. p. 61.

489:. Beuroner Kunstverlag. 1984. p. 63.

461:. Beuroner Kunstverlag. 1984. p. 62.

419:. Beuroner Kunstverlag. 1984. p. 25.

405:. Beuroner Kunstverlag. 1984. p. 22.

363:. Verlag am Klosterhof. 1998. p. 94.

154:in the middle; Christ is depicted in the

53:for the use of the preacher during Mass.

318:. Verlag am Klosterhof, St. Gallen 2008.

311:. Verlag am Klosterhof, St. Gallen 1998.

216:

137:

99:

18:

322:

64:. The book measures 398 x 235 mm.

703:

49:. It consists of texts drawn from the

56:The scribe was the monk Sintram. The

297:. Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 1984.

293:Duft, Johannes und Rudolf Schnyder:

726:9th-century illuminated manuscripts

13:

160:(almond-shaped halo), holding the

14:

737:

711:Christian illuminated manuscripts

678:

391:. Reimer. 2015. pp. 259–264.

41:that was made around 894 at the

661:

647:

633:

619:

605:

591:

577:

563:

549:

535:

521:

507:

493:

479:

465:

287:

23:Page 6 of the Evangelium longum

451:

437:

423:

409:

395:

381:

367:

353:

328:

128:

1:

671:. Reimer. 2015. p. 285.

629:. Reimer. 2015. p. 259.

447:. Reimer. 2015. p. 264.

433:. Reimer. 2015. p. 259.

7:

691:Abbey library of Saint Gall

69:abbey library of Saint Gall

10:

742:

242:

75:

342:. Christoph Flüeler. 2005

288:Reading list

133:

212:

304:. Reimer, Berlin 2015.

222:

143:

105:

33:illuminated manuscript

24:

232:Carolingian minuscule

220:

141:

103:

22:

323:Notes and references

86:dendrochronological

43:Abbey of Saint Gall

716:Ivory works of art

223:

206:Casus Sancti Galli

193:Assumption of Mary

144:

110:Casus Sancti Galli

106:

91:Casus Sancti Galli

25:

686:Evangelium longum

276:be another one".

228:Hartmut minuscule

195:and the story of

152:Christ in Majesty

29:Evangelium longum

733:

673:

672:

665:

659:

658:

651:

645:

644:

637:

631:

630:

623:

617:

616:

609:

603:

602:

595:

589:

588:

581:

575:

574:

567:

561:

560:

553:

547:

546:

539:

533:

532:

525:

519:

518:

511:

505:

504:

497:

491:

490:

483:

477:

476:

469:

463:

462:

455:

449:

448:

441:

435:

434:

427:

421:

420:

413:

407:

406:

399:

393:

392:

385:

379:

378:

371:

365:

364:

357:

351:

350:

348:

347:

332:

314:Von Euw, Anton:

58:treasure binding

741:

740:

736:

735:

734:

732:

731:

730:

701:

700:

681:

676:

667:

666:

662:

653:

652:

648:

639:

638:

634:

625:

624:

620:

611:

610:

606:

597:

596:

592:

583:

582:

578:

569:

568:

564:

555:

554:

550:

541:

540:

536:

527:

526:

522:

513:

512:

508:

499:

498:

494:

485:

484:

480:

471:

470:

466:

457:

456:

452:

443:

442:

438:

429:

428:

424:

415:

414:

410:

401:

400:

396:

387:

386:

382:

373:

372:

368:

359:

358:

354:

345:

343:

334:

333:

329:

325:

290:

269:

245:

215:

136:

131:

89:belongs to the

78:

17:

12:

11:

5:

739:

729:

728:

723:

718:

713:

699:

698:

693:

680:

679:External links

677:

675:

674:

660:

646:

632:

618:

604:

590:

576:

562:

548:

534:

520:

506:

492:

478:

464:

450:

436:

422:

408:

394:

380:

366:

352:

326:

324:

321:

320:

319:

312:

305:

298:

289:

286:

268:

265:

244:

241:

214:

211:

135:

132:

130:

127:

77:

74:

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

738:

727:

724:

722:

719:

717:

714:

712:

709:

708:

706:

697:

694:

692:

688:

687:

683:

682:

670:

664:

656:

650:

642:

636:

628:

622:

614:

608:

600:

594:

586:

580:

572:

566:

558:

552:

544:

538:

530:

524:

516:

510:

502:

496:

488:

482:

474:

468:

460:

454:

446:

440:

432:

426:

418:

412:

404:

398:

390:

384:

376:

370:

362:

356:

341:

337:

331:

327:

317:

313:

310:

306:

303:

300:Ganz, David:

299:

296:

292:

291:

285:

281:

277:

273:

264:

262:

257:

255:

249:

240:

236:

233:

229:

219:

210:

207:

201:

198:

194:

189:

187:

183:

179:

175:

171:

167:

163:

159:

158:

153:

148:

140:

126:

122:

118:

115:

111:

102:

98:

96:

92:

87:

83:

73:

70:

65:

63:

59:

54:

52:

48:

44:

40:

37:

34:

30:

21:

690:

685:

668:

663:

654:

649:

640:

635:

626:

621:

612:

607:

598:

593:

584:

579:

570:

565:

556:

551:

542:

537:

528:

523:

514:

509:

500:

495:

486:

481:

472:

467:

458:

453:

444:

439:

430:

425:

416:

411:

402:

397:

388:

383:

374:

369:

360:

355:

344:. Retrieved

339:

330:

315:

308:

301:

294:

282:

278:

274:

270:

260:

258:

253:

250:

246:

237:

227:

224:

205:

202:

190:

186:Tellus mater

162:Book of Life

155:

149:

145:

123:

119:

109:

107:

90:

79:

66:

55:

28:

26:

166:evangelists

129:Description

114:Charlemagne

95:Ekkehard IV

82:Middle Ages

47:Switzerland

39:evangeliary

705:Categories

346:2019-12-12

261:Sanctorale

340:E-codices

254:Temporale

170:Alcuin’s

157:Mandorla

689:in the

243:Content

182:Oceanus

76:History

62:Tuotilo

51:Gospels

31:is an

134:Cover

36:Latin

213:Text

197:Gall

184:and

178:Luna

176:and

27:The

174:Sol

93:by

45:in

707::

338:.

97:.

349:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.