175:, which had been completed in the late 11th century. Arabic medicine was more speculative and philosophical, drawing from the principles of Galen. Galen, as opposed to other notable physicians, believed that menstruation was a necessary and healthy purgation. Galen asserted that women are colder than men and unable to “cook” their nutrients; thus they must eliminate excess substance through menstruation. Indeed, the author presents a positive view of the role of menstruation in women's health and fertility: "Menstrual blood is special because it carries in it a living being. It works like a tree. Before bearing fruit, a tree must first bear flowers. Menstrual blood is like the flower: it must emerge before the fruit—the baby—can be born." Another condition that the author addresses at length is suffocation of the womb; this results from, among other causes, an excess of female semen (another Galenic idea). Seemingly conflicted between two different theoretical positions—one that suggested it was possible for the womb to "wander" within the body, and another which saw such movement as anatomically impossible—the author seems to admit the possibility that the womb rises to the respiratory organs. Other issues discussed at length are treatment for and the proper regimen for a newly born child. There are discussions on topics covering menstrual disorders and uterine prolapse, chapters on childbirth and pregnancy, in addition to many others. All the named authorities cited in the

221:

Green has noted, the author likely hoped for a wide audience, for he observed that women beyond the Alps would not have access to the spas that

Italian women did and therefore included instructions for an alternative steam bath. The author does not claim that the preparations he describes are his own inventions. One therapy that he claims to have personally witnessed, was created by a Sicilian woman, and he added another remedy on the same topic (mouth odor) which he himself endorses. Otherwise, the rest of the text seems to gather together remedies learned from empirical practitioners: he explicitly describes ways that he has incorporated "the rules of women whom I found to be practical in practicing the art of cosmetics." But while women may have been his sources, they were not his immediate audience: he presented his highly structured work for the benefit of other male practitioners eager, like himself, to profit from their knowledge of making women beautiful.

22:

560:("Epitome of the Histories of Salerno"). Here is the origin of the belief that "Trotula" held a chair at the university of Salerno: "There flourished in the fatherland, teaching at the university and lecturing from their professorial chairs, Abella, Mercuriadis, Rebecca, Trotta (whom some people call "Trotula"), all of whom ought to be celebrated with marvelous encomia (as Tiraqueau has noted), as well as Sentia Guarna (as Fortunatus Fidelis has said)." Green has suggested that this fiction (Salerno had no university in the 12th century, so there were no professorial chairs for men or women) may have been due to the fact that three years earlier, "

293:

34:

202:

reader how to prepare and apply medical preparations. There is a lack of cohesion, but there are sections related to gynecological, andrological, pediatric, cosmetic, and general medical conditions. Beyond a pronounced focus on treatment for fertility, there is a range of pragmatic instructions like how to “restore” virginity, as well as treatments for concerns such as difficulties with bladder control and cracked lips caused by too much kissing. In a work stressing female medical issues, remedies for men's disorders are included as well.

511:("The Book of Trotula on the Treatment of the Diseases of Women before, during, and after Birth")--Kraut and Schottus proudly emphasized "Trotula's" feminine identity. Schottus praised her as "a woman by no means of the common sort, but rather one of great experience and erudition." In his "cleaning up" of the text, Kraut had suppressed all obvious hints that this was a medieval text rather than an ancient one. When the text was next printed, in 1547 (all subsequent printings of the

504:. Kraut, seeing the disorder in the texts, but not recognizing that it was really the work of three separate authors, rearranged the entire work into 61 themed chapters. He also took the liberty of altering the text here and there. As Green has noted, "The irony of Kraut's attempt to endow 'Trotula' with a single, orderly, fully rationalized text was that, in the process, he was to obscure for the next 400 years the distinctive contributions of the historic woman Trota."

581:.) And so the stage was set for debates about "Trotula" in the 19th and 20th centuries. For those who wanted a representative of Salernitan excellence and/or female achievement, "she" could be reclaimed from the humanists' erasure. For skeptics (and there were many grounds for skepticism), it was easy to find cause for doubt that there was really any female medical authority behind this chaotic text. This was the state of affairs in the 1970s, when

548:(Aadrian DeJonghe, 1511–75), a Dutch physician who believed that textual corruptions accounted for many false attributions of ancient texts. As Green has noted, however, even though the erasure of "Trotula" was more an act of humanist editorial zeal than blatant misogyny, the fact that there were now no female authors left in the emerging canon of writers on gynecology and obstetrics was never noted.

1298:(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), chap. 5, esp. pp. 212-14 and 223; Kristian Bosselmann-Cyran, (ed.), ‘Secreta mulierum’ mit Glosse in der deutschen Bearbeitung von Johann Hartlieb, Würzburger medizinhistorische Forschungen, 36 (Pattensen/Hannover: Horst Wellm, 1985); "Ein weiterer Textzeuge von Johann Hartliebs

629:

been generated by 19th- and early 20th-century scholarship. For example, the epithet "de

Ruggiero" attached to her name was sheer invention. Likewise, claims about her date of birth or death, or who "her" husband or sons were had no foundation. (3) Most importantly, Benton announced his discovery of the

714:

was a function of the complicated textual tradition and the broad proliferation of the texts in the Middle Ages. That it is taking even longer for popular understandings of Trota and "Trotula" to catch up with this scholarship, has raised the question whether celebrations of Women's

History ought not

404:

is the most well-known image of "Trotula" (see image above). A few 13th-century references to "Trotula," however, cite her only as an authority on cosmetics. The belief that "Trotula" was the ultimate authority on the topic of women's medicine even caused works authored by others to be attributed to

269:

texts circulated for several centuries as independent texts. Each is found in several different versions, likely due to the interventions of later editors or scribes. Already by the late 12th century, however, one or more anonymous editors recognized the inherent relatedness of the three independent

673:

in the earliest known version (where it was still circulating independently), but that the text shows clear parallels to passages in other works associated with Trota and suggests strongly an intimate access to the female patient's body that, given the cultural restrictions of the time, would have

628:

and the text(s) found in medieval manuscripts, Benton was the first to prove how extensive the

Renaissance editor's emendations had been. This was not one text, and there was no "one" author. Rather, it was three different texts. (2) Benton dismantled several of the myths about "Trotula" that had

483:

was published not because it was still of immediate clinical use to learned physicians (it had been superseded in that role by a variety of other texts in the 15th century), but because it had been newly "discovered" as a witness to empirical medicine by a

Strasbourg publisher, Johannes Schottus.

224:

Six times in the original version of the text, the author credits specific practices to Muslim women, whose cosmetic practices are known to have been imitated by

Christian women on Sicily. And the text overall presents an image of an international market of spices and aromatics regularly traded in

201:

when it circulated as an independent text. However, it has been argued that it is perhaps better to refer to Trota as the "authority" who stands behind this text than its actual author. The author does not provide theories related to gynecological conditions or their causes, but simply informs the

359:

texts were finding new audiences. Almost assuredly they were, but not necessarily women. Only seven of the nearly two dozen medieval translations are explicitly addressed to female audiences, and even some of those translations were co-opted by male readers. The first documented female owner of a

278:

ensemble. These versions differ sometimes in wording, but more obviously by the addition, deletion, or rearrangement of certain material. The so-called "standardized ensemble" reflects the most mature stage of the text, and it seemed especially attractive in university settings. A survey of known

220:

ensemble) in which the author refers to himself with a masculine pronoun and explains his ambition to earn "a delightful multitude of friends" by assembling this body of learning on care of the hair (including bodily hair), face, lips, teeth, mouth, and (in the original version) the genitalia. As

705:

have been named after "Trotula," all mistakenly perpetuating fictions about "her" derived from popularizing works like that of

Chicago. Likewise, medical writers, in trying to indicate the history of women in their field, or the history of certain gynecological conditions, keep recycling outworn

700:

in 1985) presents a conflation of alleged biographical details that are no longer accepted by scholars. Chicago's celebration of "Trotula" no doubt led to the proliferation of modern websites that mention her, many of which repeat without correction the discarded misunderstandings noted above. A

391:

texts would have had no reason to doubt the attribution they found in the manuscripts, and so "Trotula" (assuming they understood the word as a personal name instead of a title) was accepted as an authority on women's medicine. The physician Petrus

Hispanus (mid-13th century), for example, cited

424:

Alongside "her" role as a medical authority, "Trotula" came to serve a new function starting in the 13th century: that of a mouthpiece for misogynous views on the nature of women. In part, this was connected to a general trend to acquire information about the "secrets of women", that is, the

1276:

Monica H. Green, “A Handlist of the Latin and

Vernacular Manuscripts of the So-Called Trotula Texts. Part II: The Vernacular Texts and Latin Re-Writings,” Scriptorium 51 (1997), 80-104, at p. 103; and Montserrat Cabré i Pairet, ‘From a Master to a Laywoman: A Feminine Manual of Self-Help’,

523:

was treated as if it were an ancient text. As Green notes, "'Trotula', therefore, in contrast to

Hildegard, survived the scrutiny of Renaissance humanists because she was able to escape her medieval associations. But it was this very success that would eventually 'unwoman' her. When the

644:

that could be used by students and scholars of the history of medicine and medieval women. However, Benton's own discoveries had rendered irrelevant any further reliance on the Renaissance edition, so Green undertook a complete survey of all the extant Latin manuscripts of the

564:

received a doctorate in philosophy at Padua, the first formal Ph.D. ever awarded to a woman. Mazza, concerned to document the glorious history of his patria, Salerno, may have been attempting to show that Padua could not claim priority in having produced female professors."

710:, as important medical figures in 12th-century Europe, did flag the importance of how historical remembrances of these women were created. That it took close to twenty years for Benton and Green to extract the historic woman Trota from the composite text of the

283:

in all its forms showed it not simply in the hands of learned physicians throughout western and central Europe, but also in the hands of monks in England, Germany, and Switzerland; surgeons in Italy and Catalonia; and even certain kings of France and England.

256:

enjoyed a pan-European circulation. These works reached their peak popularity in Latin around the turn of the 14th century. The many medieval vernacular translations carried the texts' popularity into the 15th century and, in Germany and England, the 16th.

539:

into a collection of gynecological texts. Wolf emended the author's name from "Trotula" to Eros, a freed male slave of the Roman empress Julia: "The book of women’s matters of Eros, physician freedman of Julia, whom some have absurdly named ‘Trotula’"

1393:

Monica H. Green, “In Search of an ‘Authentic’ Women’s Medicine: The Strange Fates of Trota of Salerno and Hildegard of Bingen,” Dynamis: Acta Hispanica ad Medicinae Scientiarumque Historiam Illustrandam 19 (1999), 25-54; available on-line at

1379:

Monica H. Green, “In Search of an ‘Authentic’ Women’s Medicine: The Strange Fates of Trota of Salerno and Hildegard of Bingen,” Dynamis: Acta Hispanica ad Medicinae Scientiarumque Historiam Illustrandam 19 (1999), 25-54; available on-line at

1348:

Monica H. Green, “In Search of an ‘Authentic’ Women’s Medicine: The Strange Fates of Trota of Salerno and Hildegard of Bingen,” Dynamis: Acta Hispanica ad Medicinae Scientiarumque Historiam Illustrandam 19 (1999), 25-54; available on-line at

101:: an informal community of masters and pupils who, over the course of the 12th century, developed more or less formal methods of instruction and investigation; there is no evidence of any physical or legal entity before the 13th century.

441:

attributed to "Trotula" a special authority both because of what she "felt in herself, since she was a woman", and because "all women revealed their inner thoughts more readily to her than to any man and told her their natures."

572:

was an ancient text, but he also dismissed the idea that "Trotula" could have been the text's author (working with Kraut's edition, he, too, thought it was a single text) since she was cited internally. (This is the story of

396:(d. 1260), commissioned a copy headed "Incipit liber Trotule sanatricis Salernitane de curis mulierum" ("Here begins the book of Trotula, the Salernitan female healer, on treatments for women"). Two copies of the Latin

607:

From 1544 up through the 1970s, all claims about an alleged author "Trotula," pro or con, were based on Georg Kraut's Renaissance printed text. But that was a fiction, in that it had erased all last signs that the

139:

ensemble circulated throughout Europe, reaching its greatest popularity in the 14th century. More than 130 copies exist today of the Latin texts, and over 60 copies of the many medieval vernacular translations.

1899:

1182:(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008). See also Elizabeth Dearnley, “‘Women of oure tunge cunne bettir reede and vnderstonde this langage’: Women and Vernacular Translation in Later Medieval England,” in

446:

is echoing this attitude when he includes "Trotula's" name in his "Book of Wicked Wives," a collection of anti-matrimonial and misogynous tracts owned by the Wife of Bath's fifth husband, Jankyn, as told in

1575:

The Brooklyn Museum itself has never updated its information on "Trotula," retaining, for example, the erroneous claim that she died in 1097 and that she was a "professor" at the medical school of Salerno.

248:

texts are considered the "most popular assembly of materials on women's medicine from the late twelfth through the fifteenth centuries." The nearly 200 extant manuscripts (Latin and vernacular) of the

556:

If "Trotula" as a female author had no use to humanist physicians, that was not necessarily true of other intellectuals. In 1681, the Italian historian Antonio Mazza resurrected "Trotula" in his

706:

understandings of "Trotula" (or even inventing new misunderstandings). Nevertheless, Chicago's elevation of both "Trotula" and the real Trota's contemporary, the religious and medical writer

233:

seems to capture both the empiricism of local southern Italian culture and the rich material culture made available as the Norman kings of southern Italy embraced Islamic culture on Sicily.

1550:, ed. Danielle Jacquart and Agostino Paravicini Bagliani, Edizione Nazionale ‘La Scuola medica Salernitana’, 1 (Florence: SISMEL/Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2007), 183-233; and Monica H. Green,

702:

1229:

The other image is an historiated initial that opens the copy of the intermediate ensemble in Florence, Biblioteca Laurenziana, Plut. 73, cod. 37, 13th-century (Italy), ff. 2r-41r:

304:

The trend toward using vernacular languages for medical writing began in the 12th century, and grew increasingly in the later Middle Ages. The many vernacular translations of the

1615:

1267:, ed. M. Teresa Tavormina, Medieval & Renaissance Texts and Studies, 292, 2 vols. (Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2006), vol. 2, pp. 455-568.

1958:

Lat113: Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Pal. lat. 1304 (3rd ms of 5 in codex), ff. 38r-45v, 47r-48v, 46r-v, 51r-v, 49r-50v (s. xiii, Italy): standardized ensemble:

1124:, Medieval Women: Texts and Contexts, 4 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001); Jojanneke Hulsker, ‘Liber Trotula’: Laatmiddeleeuwse vrouwengeneeskunde in de volkstaal, available online at

1870:

ensemble appeared in 2001, many libraries have been making high-quality digital images available of their medieval manuscripts. The following is a list of manuscripts of the

1900:

http://www.internetculturale.it/jmms/iccuviewer/iccu.jsp?id=oai%3Ateca.bmlonline.it%3A21%3AXXXX%3APlutei%3AIT%253AFI0100_Plutei_73.37&mode=all&teca=Laurenziana+-+FI

1904:

Lat48: London, Wellcome Library, MS 517, Miscellanea Alchemica XII (formerly Phillipps 2946), ff. 129v–134r (s. xv ex., probably Flanders): proto-ensemble (extracts),

252:

represent only a small portion of the original number that circulated around Europe from the late 12th century to the end of the 15th century. Certain versions of the

624:

texts. That study was important for three major reasons. (1) Although some previous scholars had noted discrepancies between the printed Renaissance editions of the

1944:

Lat87: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS lat. 7056, ff. 77rb-86va; 97rb-100ra (s. xiii med., England or N. France): transitional ensemble (Group B);

1099:, ed. C. Leyser and L. Smith (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2011), pp. 205-212; Monica H. Green, “Making Motherhood in Medieval England: The Evidence from Medicine,” in

392:"domina Trotula" (Lady Trotula) multiple times in his section on women's gynecological and obstetrical conditions. The Amiens chancellor, poet, and physician,

270:

Salernitan texts on women's medicine and cosmetics, and so brought them together into a single ensemble. In all, when she surveyed the entire extant corpus of

1917:

Lat50: London, Wellcome Library, MS 548, Miscellanea Medica XXII, ff. 140r-145v (s. xv med., Germany or Flanders): standardized ensemble (selections),

69:

who was associated with one of the three texts. However, "Trotula" came to be understood as a real person in the Middle Ages and because the so-called

225:

the Islamic world. Frankincense, cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg, and galangal are all used repeatedly. More than the other two texts that would make up the

348:

texts has been discovered in a 15th-century medical miscellany, held by the Biblioteca Riccardiana in Florence. This fragmentary translation of the

1910:

Lat49: London, Wellcome Library, MS 544, Miscellanea Medica XVIII, pp. 65a-72b, 63a-64b, 75a-84a (s. xiv in., France): intermediate ensemble,

352:

is here collated by the copyist (probably a surgeon making a copy for his own use) with a Latin version of the text, highlighting the differences.

296:

Illustration of a woman taking a therapeutic bath and of a medicinal tampon in a 15th-century copy of the Middle Dutch translation of the Trotula (

519:(" All Ancient Latin Physicians Who Described and Collected the Types and Remedies of Various Diseases"). From then until the 18th century, the

1892:

Lat16: Cambridge, Trinity College, MS R.14.30 (903), ff. 187r-204v (new foliation, 74r-91v) (s. xiii ex., France): proto-ensemble (incomplete),

216:("On Women's Cosmetics") is a treatise that teaches how to conserve and improve women's beauty. It opens with a preface (later omitted from the

1911:

528:

was reprinted in eight further editions between 1550 and 1572, it was not because it was the work of a woman but because it was the work of an

1979:

Fren1a: Cambridge, Trinity College, MS O.1.20 (1044), ff. 21rb-23rb (s. xiii, England): Les secres de femmes, ed. in Hunt 2011 (cited above),

1590:

400:

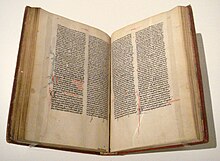

ensemble include imaginative portrayals of the author; the pen-and-ink wash image found in an early 14th-century manuscript now held by the

29:

ensemble, p. 65 (detail): pen and wash drawing meant to depict "Trotula", clothed in red and green with a white headdress, holding an orb.

2091:

1650:

ed. Lola Badia, Lluís Cifuentes, Sadurní Martí, Josep Pujol (Montserrat: Publicacions de L’Abadia de Montserrat, 2016), pp. 77–102.

1053:

William Crossgrove, "The Vernacularization of Science, Medicine, and Technology in Late Medieval Europe: Broadening Our Perspectives,"

507:

Kraut (and his publisher, Schottus) retained the attribution of the text(s) to "Trotula." In fact, in applying a singular new title--

479:

texts first appeared in print in 1544, quite late in the trend toward printing, which for medical texts had begun in the 1470s. The

2106:

93:

was widely reputed as "the most important center for the introduction of Arabic medicine into Western Europe". In referring to the

1440:

Monica H. Green, "In Search of an 'Authentic' Women’s Medicine: The Strange Fates of Trota of Salerno and Hildegard of Bingen,”

1423:

Monica H. Green, “In Search of an ‘Authentic’ Women’s Medicine: The Strange Fates of Trota of Salerno and Hildegard of Bingen,”

2116:

156:

1837:

1815:

1265:

Sex, Aging, and Death in a Medieval Medical Compendium: Trinity College Cambridge MS R.14.52, Its Texts, Language, and Scribe

40:

transitional ensemble, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS lat. 7056, mid-13th century, ff. 84v-85r, opening of the

1935:

1233:. Both manuscripts are described in Monica H. Green, “A Handlist of the Latin and Vernacular Manuscripts of the So-Called

1829:, A cura di Monica H. Green. Traduzione italiana di Valentina Brancone, Edizione Nazionale La Scuola Medica Salernitana, 4

1122:

The Knowing of Woman’s Kind in Childing: A Middle English Version of Material Derived from the ‘Trotula’ and Other Sources

53:

is a name referring to a group of three texts on women's medicine that were composed in the southern Italian port town of

696:, which features a place setting for "Trotula." The depiction here (based on publications prior to Benton's discovery of

2096:

2022:

Ital2a: London, Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, MS 532, Miscellanea Medica II, ff. 64r-70v (ca. 1465):

613:

1616:"More process, more complicated product? Monica Green on Twitter, digital (dis)information, and Women's History Month"

2111:

1755:

517:

Medici antiqui omnes qui latinis litteris diversorum morborum genera & remedia persecuti sunt, undique conquisiti

25:

London, Wellcome Library, MS 544 (Miscellanea medica XVIII), early 14th century (France), a copy of the intermediate

1169:, Lluís Cifuentes, Sadurní Martí, Josep Pujol (Montserrat: Publicacions de L’Abadia de Montserrat, 2016), pp. 77-102

312:, made somewhere in southern France in the late 12th century. The next translations, in the 13th century, were into

1306:-Bearbeitung: Der Mailänder Kodex AE.IX.34 aus der Privatbibliothek des Arztes und Literaten Albrecht von Haller,"

1986:

Fren2IIa: Kassel, Murhardsche Bibliothek der Stadt und Landesbibliothek, 4° MS med. 1, ff. 16v-20v (ca. 1430-75),

21:

1898:

Lat24: Firenze , Biblioteca Laurenziana, Plut. 73, cod. 37, ff. 2r-41r (s. xiii, Italy): intermediate ensemble,

433:, he not only elevated "Trotula's" status to that of a queen, but also paired the text with the pseudo-Albertan

364:

is Dorothea Susanna von der Pfalz, Duchess of Saxony-Weimar (1544–92), who had made for her own use a copy of

2023:

1918:

1912:

http://wellcomelibrary.org/player/b19745588#?asi=0&ai=86&z=0.1815%2C0.5167%2C0.2003%2C0.1258&r=0

1905:

1893:

1658:: Ricerche su testi medievali di medicina salernitana (trans. Valeria Gibertoni & Pina Boggi Cavallo)".

1577:

2101:

2081:

1997:

1980:

1503:

50 (1996), 137-175; Monica H. Green, “A Handlist of the Latin and Vernacular Manuscripts of the So-Called

2043:

51 (1997), 80-104; Monica H. Green, “A Handlist of the Latin and Vernacular Manuscripts of the So-Called

1482:

John F. Benton, "Trotula, Women’s Problems, and the Professionalization of Medicine in the Middle Ages,"

791:

51 (1997), 80-104; Monica H. Green, “A Handlist of the Latin and Vernacular Manuscripts of the So-Called

757:

John F. Benton, "Trotula, Women's Problems, and the Professionalization of Medicine in the Middle Ages,"

123:

to oral traditions, providing practical instructions. These works vary in both organization and content.

1473:(Turin, 1979), an Italian translation based on the 1547 Aldine (Venice) edition of Kraut's altered text.

640:

After Benton's death in 1988, Monica H. Green picked up the task of publishing a new translation of the

633:("Practical Medicine According to Trota") in a manuscript now in Madrid, which established the historic

657:

treatises were male-authored. Specifically, while Green agrees with Benton that male authorship of the

448:

1987:

1992:

Fren3a: Cambridge, Trinity College, MS O.1.20 (1044), ff. 216r–235v, s. xiii (England), ed. in Hunt,

991:, p. xi. See also Monica H. Green, “Medieval Gynecological Texts: A Handlist,” in Monica H. Green,

77:, from Spain to Poland, and Sicily to Ireland, "Trotula" has historic importance in "her" own right.

1563:

1469:. The same phenomenon occurred in Italy: P. Cavallo Boggi (ed.), M. Nubie and A. Tocco (transs.),

1101:

Motherhood, Religion, and Society in Medieval Europe, 400-1400: Essays Presented to Henrietta Leyser

1097:

Motherhood, Religion, and Society in Medieval Europe, 400-1400: Essays Presented to Henrietta Leyser

417:. Similarly, a 14th-century Catalan author entitled his work primarily focused on women's cosmetics

1445:

1428:

1395:

1381:

1350:

1095:, 2 vols. (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1994-1997), 2:76-115; Tony Hunt, “Obstacles to Motherhood,” in

816:

26 (1996), 119-203. See also Gerrit Bos, “Ibn al-Jazzār on Women’s Diseases and Their Treatment,”

932:

26 (1996), 119-203, at p. 140. The text of the original preface can be found in Monica H. Green,

620:

published a study surveying previous thinking on the question of "Trotula's" association with the

168:

1070:(Leiden: Brill, 1998); and Carmen Caballero Navas, “Algunos “secretos de mujeres” revelados: El

143:

2076:

1851:

561:

1923:

Lat81: Oxford, Pembroke College, MS 21, ff. 176r-189r (s. xiii ex., England): proto-ensemble (

1721:

Green, Monica H. (1997). "A Handlist of the Latin and Vernacular Manuscripts of the So-Called

1696:

Green, Monica H. (1996). "A Handlist of the Latin and Vernacular Manuscripts of the So-Called

313:

297:

1178:

Monica H. Green, "In a Language Women Understand: The Gender of the Vernacular," chap. 4 of

715:

include more recognition of the processes by which that record is discovered and assembled.

535:"Trotula" was "unwomaned" in 1566 by Hans Caspar Wolf, who was the first to incorporate the

2066:

1959:

1230:

582:

452:

393:

292:

1878:, the index number is given from either Green's 1996 handlist of Latin manuscripts of the

33:

8:

2071:

707:

501:

466:

2009:

Ir1b: Dublin, Trinity College, MS 1436 (E.4.1), pp. 101–107 and 359b-360b (s. xv):

1282:

1136:, ed. L. van Gemert, et al. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010), pp. 138-43;

2086:

1808:

Making Women's Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

1795:

1767:

1552:

Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

1462:

1409:

Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

1334:

Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

1321:

Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

1296:

Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

1252:

Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

1218:

Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

1197:

Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

1180:

Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

1042:

Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

960:

Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

934:

Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

891:

Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology

410:

2035:

Monica H. Green, “A Handlist of the Latin and Vernacular Manuscripts of the So-Called

1495:

Monica H. Green, “A Handlist of the Latin and Vernacular Manuscripts of the So-Called

1208:

Monica H. Green, “A Handlist of the Latin and Vernacular Manuscripts of the So-Called

1112:

Monica H. Green, “A Handlist of the Latin and Vernacular Manuscripts of the So-Called

783:

Monica H. Green, “A Handlist of the Latin and Vernacular Manuscripts of the So-Called

551:

1833:

1811:

1751:

426:

365:

98:

94:

1882:

texts, or Green's 1997 handlist of manuscripts of medieval vernacular translations.

542:

Erotis medici liberti Iuliae, quem aliqui Trotulam inepte nominant, muliebrium liber

1914:. This is the copy that includes the well-known image of “Trotula” holding an orb.

1790:

1782:

1734:

1709:

1684:

697:

684:

670:

634:

600:

591:

574:

545:

497:

443:

401:

341:

198:

58:

119:. They cover topics from childbirth to cosmetics, relying on varying sources from

1953:

1939:

693:

369:

333:

329:

309:

2010:

1932:

159:

that had just begun to make inroads into Europe. As Green demonstrated in 1996,

617:

492:("Collection of Tried-and-True Remedies of Medicine"), which also included the

409:

compendium on gynecology and obstetrics based on the works of the male authors

406:

337:

325:

321:

66:

1786:

585:

discovered "Trotula" anew. The inclusion of "Trotula" as an invited guest at

2060:

1132:. Translation, Flanders, second half of the fifteenth century,” chapter 8 in

1128:(accessed 20.xii.2009); Orlanda Lie, “What Every Midwife Needs to Know: The

1103:, ed. Conrad Leyser and Lesley Smith (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2011), pp. 173-203.

308:

were therefore part of a general trend. The first known translation was into

1738:

1713:

598:

509:

Trotulae curandarum aegritudinum muliebrium ante, in, & postpartum Liber

274:

manuscripts in 1996, Green identified eight different versions of the Latin

724:

689:

586:

135:

sometime in the late 12th century. For the next several hundred years, the

1688:

1442:

Dynamis: Acta Hispanica ad Medicinae Scientiarumque Historiam Illustrandam

1425:

Dynamis: Acta Hispanica ad Medicinae Scientiarumque Historiam Illustrandam

1279:

Dynamis: Acta Hispanica ad Medicinae Scientiarumque Historiam Illustrandam

876:(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), pp. 17-37, 70-115.

182:

2024:

http://search.wellcomelibrary.org/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1893400?lang=eng

1919:

http://search.wellcomelibrary.org/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1926717?lang=eng

1906:

http://search.wellcomelibrary.org/iii/encore/record/C__Rb1964315?lang=eng

1894:

http://sites.trin.cam.ac.uk/manuscripts/R_14_30/manuscript.php?fullpage=1

1578:

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/place_settings/trotula

1125:

74:

1998:

http://sites.trin.cam.ac.uk/manuscripts/O_1_20/manuscript.php?fullpage=1

1981:

http://sites.trin.cam.ac.uk/manuscripts/O_1_20/manuscript.php?fullpage=1

1184:

Multilingualism in Medieval Britain (c. 1066-1520): Sources and Analysis

612:

had been compiled out of the works of three different authors. In 1985,

205:

1466:

1186:, ed. J. Jefferson and A. Putter (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013), pp. 259-72.

1166:

317:

1648:

Els manuscrits, el saber i les lletres a la Corona d’Aragó, 1250-1500,

1646:: autoria i autoritat femenina en la medicina medieval en català,” in

1163:

Els manuscrits, el saber i les lletres a la Corona d’Aragó, 1250-1500,

1161:: autoria i autoritat femenina en la medicina medieval en català,” in

1145:

682:

Perhaps the best known popularization of "Trotula" was in the artwork

1875:

1546:

Monica H. Green, “Reconstructing the Oeuvre of Trota of Salerno,” in

1134:

Women’s Writing in the Low Countries 1200-1875. A Bilingual Anthology

179:

are male: Hippocrates, Oribasius, Dioscorides, Paulus, and Justinus.

155:("Book on the Conditions of Women") was novel in its adoption of the

62:

57:

in the 12th century. The name derives from a historic female figure,

653:

ensemble. Green has disagreed with Benton in his claim that all the

1988:

http://orka.bibliothek.uni-kassel.de/viewer/image/1297331763218/35/

1874:

that are now available for online consultation. In addition to the

515:

would recycle Kraut's edition), it appeared in a collection called

484:

Schottus persuaded a physician colleague, Georg Kraut, to edit the

163:

draws heavily on the gynecological and obstetrical chapters of the

975:(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), pp. 45-48.

919:(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), pp. 41-43.

906:(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), pp. 39-40.

413:

and Muscio, which in one of its four extant copies was called the

1263:

Monica H. Green and Linne R. Mooney, “The Sickness of Women”, in

824:, The Sir Henry Wellcome Asian Series (London: Kegan Paul, 1997).

197:

texts that is actually attributed to the Salernitan practitioner

90:

54:

1446:

http://www.raco.cat/index.php/Dynamis/article/view/106141/150117

1429:

http://www.raco.cat/index.php/Dynamis/article/view/106141/150117

1396:

http://www.raco.cat/index.php/Dynamis/article/view/106141/150117

1382:

http://www.raco.cat/index.php/Dynamis/article/view/106141/150117

1351:

http://www.raco.cat/index.php/Dynamis/article/view/106141/150117

677:

382:

320:. And in the 14th and 15th centuries, there are translations in

97:

in the 12th century, historians mean a school in the sense of a

2039:

Texts. Part II: The Vernacular Texts and Latin Re-Writings,”

1507:

Texts. Part II: The Vernacular Texts and Latin Re-Writings,”

1116:

Texts. Part II: The Vernacular Texts and Latin Re-Writings,”

949:(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), p. 46.

863:(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), p. 26.

850:(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), p. 22.

837:(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), p. 19.

787:

Texts. Part II: The Vernacular Texts and Latin Re-Writings,”

774:(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), p. 10.

669:(On Treatments for Women) directly attributed to the historic

1725:

Texts. Part II: The Vernacular Texts and Latin Re-Writings".

120:

1857:

1852:

http://blog.wellcomelibrary.org/2015/08/speaking-of-trotula/

80:

1068:

A History of Jewish Gynaecological Texts in the Middle Ages

993:

Women’s Healthcare in the Medieval West: Texts and Contexts

701:

clinic in Vienna and a street in modern Salerno and even a

665:

is probable, Green has demonstrated that not simply is the

568:

In 1773 in Jena, C. G. Gruner challenged the idea that the

355:

The existence of vernacular translations suggests that the

1080:

Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Hebraicos, sección Hebreo

552:

Modern debates about authorship and "Trotula's" existence

193:("On Treatments for Women") is the only one of the three

1960:

http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/bav_pal_lat_1304

1768:"The Trotula: a medieval compendium of women's medicine"

1591:"Making a disease from a remedy: Trotula and vaginismus"

1513:

The 'Trotula': A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine

1231:

http://www.bml.firenze.sbn.it/Diaita/schede/scheda15.htm

1216:

50 (1996), 137-175, at pp. 157-58; and Monica H. Green,

1003:

1001:

973:

The ‘Trotula’: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine

947:

The ‘Trotula’: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine

917:

The ‘Trotula’: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine

904:

The ‘Trotula’: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine

874:

The ‘Trotula’: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine

861:

The ‘Trotula’: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine

848:

The ‘Trotula’: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine

835:

The ‘Trotula’: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine

772:

The ‘Trotula’: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine

746:

The ‘Trotula’: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine

1827:

Trotula. Un compendio medievale di medicina delle donne

1515:(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001).

748:(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001).

89:

In the 12th century, the southern Italian port town of

1748:

The Trotula: a medieval compendium of women's medicine

1283:

http://www.ugr.es/~dynamis/completo20/PDF/Dyna-12.PDF

998:

488:, which Schottus then included in a volume he called

344:. Most recently, a Catalan translation of one of the

236:

131:

circulated anonymously until they were combined with

1511:

51 (1997), 80-104; Monica H. Green, ed. and trans.,

1471:

Trotula de Ruggiero : Sulle malatie delle donne

1411:(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 279-80.

1044:(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 325-39.

822:

Ibn al-Jazzar on Sexual Diseases and Their Treatment

820:

37 (1993), 296-312; and Gerrit Bos, ed. and trans.,

577:'s cure of the woman with "wind" in the womb in the

1554:(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 29-69.

1533:Monica H. Green, “The Development of the Trotula,”

1336:(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), chapter 6.

1254:(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 84-85.

962:(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 45-48.

936:(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 45-46.

928:Monica H. Green, “The Development of the Trotula,”

893:(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 53-65.

674:likely only been allowed to a female practitioner.

595:(1974–79), insured that the debate would continue.

458:

425:processes of generation. When the Munich physician

287:

1548:La Scuola medica Salernitana: Gli autori e i testi

727:, mentioned in the Trotula manuscripts as a remedy

1671:Green, Monica H. (1996). "The Development of the

1444:19 (1999), 25-54, at p. 40; available on-line at

1427:19 (1999), 25-54, at p. 39; available on-line at

421:("The Book ... which is called 'Trotula'").

2058:

1846:Green, Monica H. (2015). "Speaking of Trotula".

1323:(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 223.

1220:(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 331.

1199:(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 342.

995:(Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), Appendix, pp. 1-36.

171:'s Latin translation of Ibn al-Jazzar's Arabic

1954:http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9076918w

1654:Green, Monica H. (1995). "Estraendo Trota dal

1642:Cabré i Pairet, Montserrat. “Trota, Tròtula i

1459:Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society

2011:https://www.isos.dias.ie/TCD/TCD_MS_1436.html

1933:http://digital-collections.pmb.ox.ac.uk/ms-21

1157:Montserrat Cabré i Pairet, “Trota, Tròtula i

637:'s claim to have existed and been an author.

1750:. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

368:’s paired German translations of the pseudo-

16:Three 12th-century texts on women's medicine

1566:. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved on 2015-08-06.

1419:

1417:

1120:51 (1997), 80-104; Alexandra Barratt, ed.,

885:On Trota's relationship to the text of the

429:(d. 1468) made a German translation of the

1866:Since Green's edition of the standardized

1832:. Florence: SISMEL/Edizioni del Galluzzo.

1537:26 (1996), 119-203, at pp. 137 and 152-57.

1308:Würzburger medizinhistorische Mitteilungen

1241:50 (1996), 137-175, at pp. 146-47 and 153.

1007:Green, Monica H. “The Development of the

761:59, no. 1 (Spring 1985), 330-53, at p. 33.

1794:

1362:Monica H. Green, “The Development of the

808:Monica H. Green, “The Development of the

558:Historiarum Epitome de rebus salernitanis

2047:Texts. Part I: The Latin Manuscripts,”

1499:Texts. Part I: The Latin Manuscripts,”

1414:

1237:Texts. Part I: The Latin Manuscripts,”

1212:Texts. Part I: The Latin Manuscripts,”

795:Texts. Part I: The Latin Manuscripts,”

419:Lo libre . . . al qual a mes nom Trotula

291:

115:are usually referred to collectively as

32:

20:

1700:Texts. Part I: The Latin Manuscripts".

1138:CELT: Corpus of Electronia Texts. The

260:

2059:

1765:

1126:http://www.historischebronnenbrugge.be

1824:

1805:

1745:

1720:

1695:

1670:

1653:

1613:

1344:

1342:

1850:, Wellcome Library, 13 August 2015.

1588:

1810:. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

1484:Bulletin of the History of Medicine

1146:http://www.ucc.ie/celt/trotula.html

759:Bulletin of the History of Medicine

678:"Trotula's" fame in popular culture

383:"Trotula's" fame in the Middle Ages

147:("Book on the Conditions of Women")

73:texts circulated widely throughout

13:

2092:12th-century Italian women writers

2029:

1636:

1457:Susan Mosher Stuard, "Dame Trot,"

1339:

692:, now on permanent exhibit at the

614:California Institute of Technology

471:and early debates about authorship

14:

2128:

1074:y la recepción y transmisión del

971:Monica H. Green, ed. and trans.,

945:Monica H. Green, ed. and trans.,

915:Monica H. Green, ed. and trans.,

902:Monica H. Green, ed. and trans.,

872:Monica H. Green, ed. and trans.,

859:Monica H. Green, ed. and trans.,

846:Monica H. Green, ed. and trans.,

833:Monica H. Green, ed. and trans.,

777:

770:Monica H. Green, ed. and trans.,

1461:1, no. 2 (Winter 1975), 537-42,

744:Monica H. Green, ed. and trans.

288:Medieval vernacular translations

2107:12th-century Italian physicians

1766:Nutton, Vivian (January 2003).

1614:Green, Monica H. (2017-03-04).

1607:

1582:

1569:

1557:

1540:

1527:

1518:

1489:

1486:59, no. 1 (Spring 1985), 30–53.

1476:

1451:

1434:

1401:

1387:

1373:

1356:

1326:

1313:

1288:

1270:

1257:

1244:

1223:

1202:

1189:

1172:

1151:

1106:

1085:

1060:

1047:

1034:

1018:

978:

965:

952:

939:

922:

909:

896:

879:

177:Liber de sinthomatibus mulierum

153:Liber de sinthomatibus mulierum

145:Liber de sinthomatibus mulierum

1825:Green, Monica H., ed. (2009).

1370:26 (1996), 119-203, at p. 157.

866:

853:

840:

827:

802:

764:

751:

738:

589:'s feminist art installation,

1:

2117:12th-century writers in Latin

1746:Green, Monica H, ed. (2001).

731:

85:texts: genesis and authorship

1858:Medieval Manuscripts of the

1660:Rassegna Storica Salernitana

532:("a very ancient author")."

467:Renaissance editions of the

405:her, such as a 15th-century

7:

1677:Revue d'Histoire des Textes

1535:Revue d’Histoire des Textes

1368:Revue d’Histoire des Textes

1057:5, no. 1 (2000), pp. 47-63.

1013:Revue d’Histoire des Textes

930:Revue d’Histoire des Textes

814:Revue d’Histoire des Textes

718:

451:(Prologue, (D), 669–85) of

237:The Medieval legacy of the

186:("On Treatments for Women")

10:

2133:

1589:King, Helen (2017-06-08).

1055:Early Science and Medicine

703:corona on the planet Venus

2097:Medieval women physicians

1806:Green, Monica H. (2008).

1787:10.1017/S002572730005660X

649:and a new edition of the

490:Experimentarius medicinae

459:The modern legacy of the

2112:Italian women physicians

631:Practica secundum Trotam

387:Medieval readers of the

209:("On Women’s Cosmetics")

1983:(see also Fren3 below)

1739:10.3406/scrip.1997.1796

1714:10.3406/scrip.1996.1754

1142:Ensemble of Manuscripts

889:, see Monica H. Green,

449:The Wife of Bath's Tale

169:Constantine the African

1967:Vernacular Manuscripts

1285:, accessed 02/14/2014.

694:Brooklyn Museum of Art

544:). The idea came from

500:'s near contemporary,

301:

298:Bruges, Public Library

45:

30:

1996:, II (1997), 76–107,

1994:Anglo-Norman Medicine

1689:10.3406/rht.1996.1441

1093:Anglo-Norman Medicine

603:in modern scholarship

295:

36:

24:

583:second-wave feminism

530:antiquissimus auctor

453:The Canterbury Tales

394:Richard de Fournival

279:owners of the Latin

261:Circulation in Latin

133:Treatments for Women

109:Treatments for Women

2102:People from Salerno

2082:History of medicine

2051:50 (1996), 137-175.

1848:Early Medicine Blog

1595:Mistaking Histories

1281:20 (2000), 371–93,

1082:55 (2006), 381-425.

1015:26 (1996), 119-203.

799:50 (1996), 137-175.

708:Hildegard of Bingen

659:Conditions of Women

599:The reclamation of

502:Hildegard of Bingen

439:Placides and Timeus

161:Conditions of Women

157:new Arabic medicine

125:Conditions of Women

105:Conditions of Women

1938:2015-12-16 at the

1310:13 (1995), 209–15.

411:Gilbertus Anglicus

302:

231:De ornatu mulierum

214:De ornatu mulierum

207:De ornatu mulierum

46:

42:De ornatu mulierum

31:

1887:Latin Manuscripts

1839:978-88-8450-336-7

1817:978-0-19-921149-4

1407:Monica H. Green,

1332:Monica H. Green,

1319:Monica H. Green,

1294:Monica H. Green,

1250:Monica H. Green,

1195:Monica H. Green,

1040:Monica H. Green,

958:Monica H. Green,

887:De curis mulierum

667:De curis mulierum

663:Women's Cosmetics

579:De curis mulierum

427:Johannes Hartlieb

366:Johannes Hartlieb

350:De curis mulierum

191:De curis mulierum

184:De curis mulierum

129:Women’s Cosmetics

113:Women’s Cosmetics

99:school of thought

95:School of Salerno

2124:

2052:

2033:

1843:

1821:

1800:

1798:

1772:

1761:

1742:

1717:

1692:

1667:

1630:

1629:

1627:

1626:

1611:

1605:

1604:

1602:

1601:

1586:

1580:

1573:

1567:

1561:

1555:

1544:

1538:

1531:

1525:

1522:

1516:

1493:

1487:

1480:

1474:

1455:

1449:

1438:

1432:

1421:

1412:

1405:

1399:

1391:

1385:

1377:

1371:

1360:

1354:

1346:

1337:

1330:

1324:

1317:

1311:

1300:Secreta mulierum

1292:

1286:

1274:

1268:

1261:

1255:

1248:

1242:

1227:

1221:

1206:

1200:

1193:

1187:

1176:

1170:

1155:

1149:

1110:

1104:

1089:

1083:

1064:

1058:

1051:

1045:

1038:

1032:

1029:

1022:

1016:

1005:

996:

989:

982:

976:

969:

963:

956:

950:

943:

937:

926:

920:

913:

907:

900:

894:

883:

877:

870:

864:

857:

851:

844:

838:

831:

825:

806:

800:

781:

775:

768:

762:

755:

749:

742:

698:Trota of Salerno

685:The Dinner Party

671:Trota of Salerno

635:Trota of Salerno

601:Trota of Salerno

592:The Dinner Party

575:Trota of Salerno

546:Hadrianus Junius

498:Trota of Salerno

444:Geoffrey Chaucer

437:. A text called

435:Secrets of Women

415:Liber Trotularis

402:Wellcome Library

377:Das Buch Trotula

373:Secrets of Women

199:Trota of Salerno

59:Trota of Salerno

2132:

2131:

2127:

2126:

2125:

2123:

2122:

2121:

2057:

2056:

2055:

2034:

2030:

1940:Wayback Machine

1864:

1840:

1818:

1775:Medical History

1770:

1758:

1639:

1637:Further reading

1634:

1633:

1624:

1622:

1612:

1608:

1599:

1597:

1587:

1583:

1574:

1570:

1562:

1558:

1545:

1541:

1532:

1528:

1524:Benton, pp. 46.

1523:

1519:

1494:

1490:

1481:

1477:

1456:

1452:

1439:

1435:

1422:

1415:

1406:

1402:

1392:

1388:

1378:

1374:

1361:

1357:

1353:, at pp. 33-34.

1347:

1340:

1331:

1327:

1318:

1314:

1293:

1289:

1275:

1271:

1262:

1258:

1249:

1245:

1228:

1224:

1207:

1203:

1194:

1190:

1177:

1173:

1156:

1152:

1111:

1107:

1090:

1086:

1065:

1061:

1052:

1048:

1039:

1035:

1027:

1023:

1019:

1006:

999:

987:

983:

979:

970:

966:

957:

953:

944:

940:

927:

923:

914:

910:

901:

897:

884:

880:

871:

867:

858:

854:

845:

841:

832:

828:

818:Medical History

807:

803:

782:

778:

769:

765:

756:

752:

743:

739:

734:

721:

680:

605:

554:

473:

464:

385:

370:Albertus Magnus

290:

263:

242:

211:

188:

149:

87:

75:medieval Europe

17:

12:

11:

5:

2130:

2120:

2119:

2114:

2109:

2104:

2099:

2094:

2089:

2084:

2079:

2074:

2069:

2054:

2053:

2027:

1863:

1856:

1855:

1854:

1844:

1838:

1822:

1816:

1803:

1802:

1801:

1756:

1743:

1718:

1708:(1): 137–175.

1693:

1683:(1): 119–203.

1668:

1651:

1638:

1635:

1632:

1631:

1606:

1581:

1568:

1564:Place Settings

1556:

1539:

1526:

1517:

1488:

1475:

1450:

1433:

1413:

1400:

1386:

1372:

1355:

1338:

1325:

1312:

1287:

1269:

1256:

1243:

1222:

1201:

1188:

1171:

1150:

1105:

1084:

1059:

1046:

1033:

1017:

997:

977:

964:

951:

938:

921:

908:

895:

878:

865:

852:

839:

826:

801:

776:

763:

750:

736:

735:

733:

730:

729:

728:

720:

717:

679:

676:

618:John F. Benton

604:

597:

553:

550:

472:

465:

463:

457:

407:Middle English

384:

381:

326:Middle English

289:

286:

262:

259:

241:

235:

229:ensemble, the

210:

204:

187:

181:

173:Zad al-musafir

148:

142:

86:

79:

67:medical writer

15:

9:

6:

4:

3:

2:

2129:

2118:

2115:

2113:

2110:

2108:

2105:

2103:

2100:

2098:

2095:

2093:

2090:

2088:

2085:

2083:

2080:

2078:

2077:Sexual health

2075:

2073:

2070:

2068:

2065:

2064:

2062:

2050:

2046:

2042:

2038:

2032:

2028:

2026:

2025:

2020:

2019:

2018:

2013:

2012:

2007:

2006:

2005:

2000:

1999:

1995:

1990:

1989:

1984:

1982:

1977:

1976:

1975:

1970:

1969:

1968:

1963:

1961:

1956:

1955:

1951:

1947:

1942:

1941:

1937:

1934:

1930:

1926:

1921:

1920:

1915:

1913:

1908:

1907:

1902:

1901:

1896:

1895:

1890:

1889:

1888:

1883:

1881:

1877:

1873:

1869:

1861:

1853:

1849:

1845:

1841:

1835:

1831:

1828:

1823:

1819:

1813:

1809:

1804:

1797:

1792:

1788:

1784:

1780:

1776:

1771:(book review)

1769:

1763:

1762:

1759:

1757:0-8122-3589-4

1753:

1749:

1744:

1740:

1736:

1733:(1): 80–104.

1732:

1728:

1724:

1719:

1715:

1711:

1707:

1703:

1699:

1694:

1690:

1686:

1682:

1678:

1674:

1669:

1665:

1661:

1657:

1652:

1649:

1645:

1641:

1640:

1621:

1617:

1610:

1596:

1592:

1585:

1579:

1572:

1565:

1560:

1553:

1549:

1543:

1536:

1530:

1521:

1514:

1510:

1506:

1502:

1498:

1492:

1485:

1479:

1472:

1468:

1464:

1460:

1454:

1447:

1443:

1437:

1430:

1426:

1420:

1418:

1410:

1404:

1397:

1390:

1383:

1376:

1369:

1365:

1359:

1352:

1345:

1343:

1335:

1329:

1322:

1316:

1309:

1305:

1301:

1297:

1291:

1284:

1280:

1273:

1266:

1260:

1253:

1247:

1240:

1236:

1232:

1226:

1219:

1215:

1211:

1205:

1198:

1192:

1185:

1181:

1175:

1168:

1164:

1160:

1154:

1147:

1143:

1139:

1135:

1131:

1127:

1123:

1119:

1115:

1109:

1102:

1098:

1094:

1088:

1081:

1078:en hebreo ,”

1077:

1073:

1069:

1063:

1056:

1050:

1043:

1037:

1030:

1021:

1014:

1010:

1004:

1002:

994:

990:

981:

974:

968:

961:

955:

948:

942:

935:

931:

925:

918:

912:

905:

899:

892:

888:

882:

875:

869:

862:

856:

849:

843:

836:

830:

823:

819:

815:

811:

805:

798:

794:

790:

786:

780:

773:

767:

760:

754:

747:

741:

737:

726:

723:

722:

716:

713:

709:

704:

699:

695:

691:

687:

686:

675:

672:

668:

664:

660:

656:

652:

648:

643:

638:

636:

632:

627:

623:

619:

615:

611:

602:

596:

594:

593:

588:

584:

580:

576:

571:

566:

563:

562:Elena Cornaro

559:

549:

547:

543:

538:

533:

531:

527:

522:

518:

514:

510:

505:

503:

499:

495:

491:

487:

482:

478:

470:

462:

456:

454:

450:

445:

440:

436:

432:

428:

422:

420:

416:

412:

408:

403:

399:

395:

390:

380:

378:

374:

371:

367:

363:

358:

353:

351:

347:

343:

339:

335:

331:

327:

323:

319:

315:

311:

307:

299:

294:

285:

282:

277:

273:

268:

258:

255:

251:

247:

240:

234:

232:

228:

222:

219:

215:

208:

203:

200:

196:

192:

185:

180:

178:

174:

170:

166:

162:

158:

154:

146:

141:

138:

134:

130:

126:

122:

118:

114:

110:

106:

102:

100:

96:

92:

84:

78:

76:

72:

68:

64:

60:

56:

52:

51:

43:

39:

35:

28:

23:

19:

2048:

2044:

2040:

2036:

2031:

2021:

2016:

2015:

2014:

2008:

2003:

2002:

2001:

1993:

1991:

1985:

1978:

1973:

1972:

1971:

1966:

1965:

1964:

1957:

1949:

1945:

1943:

1931:(fragment),

1928:

1924:

1922:

1916:

1909:

1903:

1897:

1891:

1886:

1885:

1884:

1879:

1871:

1867:

1865:

1859:

1847:

1830:

1826:

1807:

1781:(1): 136–7.

1778:

1774:

1764:reviewed at

1747:

1730:

1726:

1722:

1705:

1701:

1697:

1680:

1676:

1672:

1663:

1659:

1655:

1647:

1643:

1623:. Retrieved

1619:

1609:

1598:. Retrieved

1594:

1584:

1571:

1559:

1551:

1547:

1542:

1534:

1529:

1520:

1512:

1508:

1504:

1500:

1496:

1491:

1483:

1478:

1470:

1458:

1453:

1441:

1436:

1424:

1408:

1403:

1389:

1375:

1367:

1363:

1358:

1333:

1328:

1320:

1315:

1307:

1304:Buch Trotula

1303:

1299:

1295:

1290:

1278:

1272:

1264:

1259:

1251:

1246:

1238:

1234:

1225:

1217:

1213:

1209:

1204:

1196:

1191:

1183:

1179:

1174:

1162:

1158:

1153:

1141:

1137:

1133:

1129:

1121:

1117:

1113:

1108:

1100:

1096:

1092:

1087:

1079:

1075:

1071:

1067:

1066:Ron Barkaï,

1062:

1054:

1049:

1041:

1036:

1026:The 'Trotula

1025:

1020:

1012:

1008:

992:

986:The 'Trotula

985:

980:

972:

967:

959:

954:

946:

941:

933:

929:

924:

916:

911:

903:

898:

890:

886:

881:

873:

868:

860:

855:

847:

842:

834:

829:

821:

817:

813:

809:

804:

796:

792:

788:

784:

779:

771:

766:

758:

753:

745:

740:

725:Sator Square

711:

690:Judy Chicago

683:

681:

666:

662:

658:

654:

650:

646:

641:

639:

630:

625:

621:

609:

606:

590:

587:Judy Chicago

578:

569:

567:

557:

555:

541:

536:

534:

529:

525:

520:

516:

512:

508:

506:

493:

489:

485:

480:

476:

474:

468:

460:

438:

434:

430:

423:

418:

414:

397:

388:

386:

376:

372:

361:

360:copy of the

356:

354:

349:

345:

314:Anglo-Norman

305:

303:

280:

275:

271:

266:

264:

253:

249:

245:

243:

238:

230:

226:

223:

217:

213:

212:

206:

194:

190:

189:

183:

176:

172:

164:

160:

152:

150:

144:

136:

132:

128:

124:

116:

112:

108:

104:

103:

88:

82:

70:

49:

48:

47:

41:

37:

26:

18:

2067:Gynaecology

2049:Scriptorium

2041:Scriptorium

1948:(Urtext of

1727:Scriptorium

1702:Scriptorium

1666:(1): 31–53.

1509:Scriptorium

1501:Scriptorium

1398:, at p. 37.

1384:, at p. 34.

1239:Scriptorium

1214:Scriptorium

1118:Scriptorium

1091:Tony Hunt,

1072:Še’ar yašub

797:Scriptorium

789:Scriptorium

300:, Ms. 593).

117:The Trotula

2072:Obstetrics

2061:Categories

1625:2017-06-07

1620:Historiann

1600:2017-06-08

1167:Lola Badia

732:References

688:(1979) by

616:historian

318:Old French

265:All three

2087:Cosmetics

1876:shelfmark

332:(again),

63:physician

1936:Archived

1031:, p. 58.

719:See also

165:Viaticum

2045:Trotula

2037:Trotula

2017:Italian

1927:only);

1880:Trotula

1872:Trotula

1868:Trotula

1860:Trotula

1796:1044789

1723:Trotula

1698:Trotula

1673:Trotula

1656:Trotula

1644:Tròtula

1505:Trotula

1497:Trotula

1467:3173063

1364:Trotula

1235:Trotula

1210:Trotula

1159:Tròtula

1140:Trotula

1130:Trotula

1114:Trotula

1076:Trotula

1024:Green,

1009:Trotula

984:Green,

810:Trotula

793:Trotula

785:Trotula

712:Trotula

655:Trotula

651:Trotula

647:Trotula

642:Trotula

626:Trotula

622:Trotula

610:Trotula

570:Trotula

537:Trotula

526:Trotula

521:Trotula

513:Trotula

494:Physica

486:Trotula

481:Trotula

477:Trotula

469:Trotula

461:Trotula

431:Trotula

398:Trotula

389:Trotula

362:Trotula

357:Trotula

346:Trotula

342:Italian

306:Trotula

281:Trotula

276:Trotula

272:Trotula

267:Trotula

254:Trotula

250:Trotula

246:Trotula

239:Trotula

227:Trotula

218:Trotula

195:Trotula

137:Trotula

91:Salerno

83:Trotula

71:Trotula

55:Salerno

50:Trotula

38:Trotula

27:Trotula

1974:French

1836:

1814:

1793:

1754:

1465:

340:, and

334:German

330:French

310:Hebrew

111:, and

2004:Irish

1862:Texts

1463:JSTOR

1302:-und

1028:'

988:'

338:Irish

322:Dutch

121:Galen

1834:ISBN

1812:ISBN

1752:ISBN

1165:ed.

661:and

475:The

375:and

316:and

244:The

151:The

127:and

81:The

65:and

61:, a

1952:),

1950:LSM

1946:TEM

1929:DOM

1925:LSM

1791:PMC

1783:doi

1735:doi

1710:doi

1685:doi

1675:".

1366:,”

1011:,”

812:,”

496:of

2063::

1962:.

1789:.

1779:47

1777:.

1773:.

1731:51

1729:.

1706:50

1704:.

1681:26

1679:.

1664:24

1662:.

1618:.

1593:.

1416:^

1341:^

1144:,

1000:^

455:.

379:.

336:,

328:,

324:,

167:,

107:,

1842:.

1820:.

1799:.

1785::

1760:.

1741:.

1737::

1716:.

1712::

1691:.

1687::

1628:.

1603:.

1448:.

1431:.

1148:.

540:(

44:.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.